Hilary Mantel, the two-time Booker Prize-winning author of the bestselling Wolf Hall trilogy, has died aged seventy, her publisher has confirmed.

Mantel passed away on Thursday at a hospital in Exeter, England, from a stroke. Her publisher said she died ‘suddenly yet peacefully’, surrounded by close family and friends.

In a statement, her publisher said Mantel was ‘one of the greatest English novelists of this century’ and that ‘her beloved works are considered modern classics’:

‘We are heartbroken at the death of our beloved author, Dame Hilary Mantel, and our thoughts are with her friends and family, especially her husband, Gerald.

‘This is a devastating loss and we can only be grateful she left us with such a magnificent body of work.’

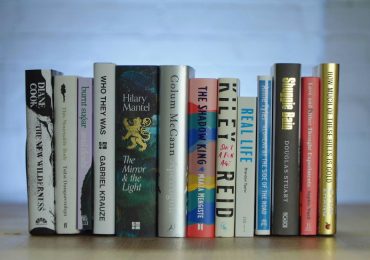

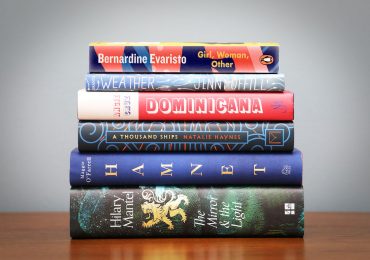

Mantel’s Booker Prize-winning 2009 novel Wolf Hall, a fictional account of Thomas Cromwell’s rise to power at the time of King Henry VIII, is considered to be responsible for re-energising historical fiction as a genre. She won a second Booker for its sequel, Bring Up the Bodies, published in 2012, with the third instalment, The Mirror and the Light, released in 2020, being longlisted for the Booker Prize and shortlisted for the Women’s Prize.

The Cromwell trilogy sold more than five million copies globally and has been translated into forty-one languages.

Mantel was born in Derbyshire in the United Kingdom, the eldest of three children. She studied law at the London School of Economics and the University of Sheffield, and worked in social work and retail before marrying her husband, Gerald McEwen, a geologist, in 1973. In 1977, the couple moved to Botswana, where they lived for five years. During this time, Mantel, then in her early twenties, worked as a social worker and began writing A Place of Greater Safety, an extraordinary 760-page novel about the French Revolution, which she struggled to find a publisher for. It was finally released in 1992, as her fifth published novel.

After leaving Botswana, Mantel spent four years in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, and after returning to England worked as the film critic for The Spectator. She and her husband divorced in 1981 but remarried in 1982, with McEwen later giving up his work in geology to manage his wife’s career, as she became a literary sensation.

Mantel finally managed to get her first novel, Every Day is Mother’s Day, published in 1985, when she was thirty-five, and its sequel, Vacant Possession, was released a year later. Her twelve novels and numerous short stories set forth her bleakly comic outlook and exceptionally keen understanding of the social condition.

During her twenties, Mantel suffered from a debilitating long-term illness that went undiagnosed for many years. Initially, a psychiatric illness was suspected, and she was hospitalised and treated with antipsychotic drugs that she believes produced psychotic symptoms, causing her to avoid seeking help for some time. Through her own research, while living in Botswana, she discovered that the cause of her ill health was probably a severe form of endometriosis, a disease little understood at the time.

Mantel wrote extensively about her struggles with her health, and in her 2003 memoir, Giving Up the Ghost; she revealed the impact of it on her intellectual worldview, writing: ‘If, like me, you have a surgical menopause at the age of twenty-seven, you’ve thought your way through questions of fertility and menopause and what it means to be without children because it all happened catastrophically.’

Mantel was the first woman and the first Briton to win the Booker Prize twice. Her other awards include the National Book Critics Circle Award and Walter Scott Prize, for Wolf Hall, the Costa Book Award, for Bring Up the Bodies, a British Academy President’s Medal, the Kenyon Review Award for Literary Achievement, and honorary degrees from Sheffield Hallam University, the University of Exeter, Kingston University, the University of Cambridge, the University of Derby, Bath Spa University, the University of Oxford and Oxford Brookes University. She was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 2006 and Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBE) in 2014, for services to literature.

In a 2017 lecture titled ‘I Met a Man Who Wasn’t There’, Mantel said:

‘If you’re writing about a real person, make sure to choose somebody you really don’t understand. You know the old saying, write what you know? I am dubious about write what you know, because I’ve always thought that in any type of fiction, you write to find out, not even to settle on an answer, but to pose the most acute question.

‘If everything yields to the eye, at first glance, you’ll bore yourself and your reader. Better have a puzzle, have a mystery, and don’t count on solving it.

‘Now, when I say a puzzle, I don’t mean a puzzle as in a detective story, and I don’t just mean a subject or theme that is intricate, or one that is complex, layered. I mean a puzzle that is human and thus never solved, because you never arrive at perfect understanding, even with the people you live with, let alone those who are dead and gone.’