The Blinded City by Matthew Wilhelm-Solomon is a lucidly fascinating immersion into the world of the people who occupy the ‘dark buildings’ of Johannesburg, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

The Blinded City

Matthew Wilhelm-Solomon

Picador, 2022

Johannesburg—not the dusty collection of prospectors’ shacks and fanciful stately home approximations of the nineteenth century, but the big city that unpromising scene became—was first elision and then collision. It is the product of a sulphurous burst of twentieth-century modernity: it sprang from an imaginary that perceived of progress in terms of accelerative growth—upwards, outwards, covering over and palimpsesting. As a project of supremacist modernity, it was arranged around the mercenary needs of twentieth-century South Africa’s collectively exploitative fantasy. Buildings proliferated wastefully in the attempt to create a smoothed urban centre that would defy imperial feelings about Johannesburg’s provinciality. Grand houses were swept away for tall buildings. Forests that were themselves artificial were trimmed for highways that scarred the landscape and bent the city to the whims of automobility.

Writing of Johannesburg as far back as the nineteen-fifties, pre-eminent architectural critic Nikolaus Pevsner observed:

The original mining camp was divided into square blocks 206 foot each way and had a plain grid pattern of streets. On this American pattern the town grew, and the centre is laid out entirely like that. An occasional grouping of two blocks together to allow space for the City Hall or the Law Courts or the station, and an occasional leaving of one block to the municipal gardens department is all that punctuates the plan. Moreover, the centre is on flat land. There is nothing attractive there, neither English variety and surprise, nor French scale and grandeur. And when vertical development began in the centre, no control was established over the placing of skyscrapers, so that the pattern has no more composition in the third dimension than in length and width.

A dense sprawl of fanciful corporate towers, morose textile factories, trendy inner-city boasts for clients who did not exist in sufficient droves (the proliferation of suburban sprawl revealed the population’s true desire for habitation), municipal repositories and other concrete components, Johannesburg instructs us in how not to build a city. It is a car-dependent metropolis whose streets are a contextually rapid superimposed history of the country’s mendacious past: getting a leapfrog on other built projections of modernity, it boomed quickly, and it sagged quickly. These things are what are supposed to produce the rich layers of urbanistic complexity, but it became unmanageable, and dreams that become unmanageable are nightmares.

So it was that the Johannesburg dream began to fray at its overlooked points. As Black people defied the despicable population restrictions to make homes for themselves in the city, so the city entered its entropic phase. This is often characterised as a time of white flight, but it was simply the inevitable process of living somewhere that was an idea, not a physical location. The idea simply upped and dispersed itself to the sterile office-park remaking of the city in terms that mirrored the historical reality. Where its value had been as a symbol of white development (a crude lie, easily exposed), in the twilight years of the twentieth century, it took on a new value proposition: as raw material for the task of living.

What is to be done with the excess generated by modernity? Cities render bad thinking concrete. Many of the buildings that pooled on the (spread-out) city centre presumed a kind of fixity of purpose that would be cruelly disproved decades later. Those buildings that were not valuable enough to mothball (for posterity? For the return of the Good Old Days?) were taken on by new tenants with their own orders of legitimacy and their own sense of order, which patently disregarded the salubrious inhabitation mores and building codes of the old system. In a weird inversion, the modernist buildings became cheek-by-jowl tenements, improbably improvised bedsits, vertical towers of relentless squalor.

In the largely white public imaginary that devotes itself to opining the loss of the old apartheid world, Johannesburg is treated as some sort of lapsarian fable whose ogre is a careless and undeserving Black government. Nostalgia groups on social media mourn for the disappeared ephemera of a Johannesburg in which white people belonged to the durative present (replete with memories of Fontana chicken and seedy Hillbrow discotheques), rather than the archived past. Rose-tinted remembrances mingle with rancorous bitterness about the imagined sordid goings-on in the CBD they haven’t dared to visit since The Fall. In their decrying is the plaintive sense that there is some obligation on the part of the state to ensure the flourishing of the imagined city, which is an anecdotal bricolage of no-crime/good-times/no-blacks.

The same conditions that have generated this miserabilist whenweism have also given rise to an industry of psychogeographic writing about the economic, demographic and infrastructural shifts in the makeup of the Johannesburg metropolis. A composite sort of book emerges, where Theory cohabits with sentimental narrative in what often amounts to an attempt to recover a commons from adverse disparity (what the Regeneration Community often terms vibrant urbanism). Much of it is compelling and readable, from the ruminative is-it-fiction of Ivan Vladislavić and the late Harry Kalmer to the numerous academic monographs that take the measure of the city and the feelings it produces in those who inhabit it. I am not sure what it says about the state of things that the genre is proliferated mainly by white authors, for that is a fact that cannot easily be explained away. Certainly, there is more than a faint suspicion that the whiteness of the genre is symptomatic of the truism that for Black people Johannesburg has always been a more complex place, a contingent and uncertain space, always bisected by threat and promise.

Perhaps the very performativeness of this Joburg-enthusiasm seems like special pleading, but it suggests a desire to evince a more robust (don’t say resilient) citizen-ness, where almond-milk flat-white cafes abut ruined buildings that are simultaneously shelter and recycling resource. In place of the sham-city of yesteryear, this concern with forging a more richly textured sense of the flexible commons suggests the possibility of assertive urban space, marked by provisional celebrations, demanding encounters, earnest resilience, and a quietly thumbed nose at the risible sensibilities of that other city, the one by the sea.

***

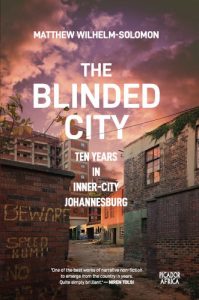

Matthew Wilhelm-Solomon’s The Blinded City: Ten Years in Inner-City Johannesburg bears obvious kinship with such books. But in its subject matter and format, it would be more accurately comparable to such works as Sean Christie’s Under Nelson Mandela Boulevard, which brought readers into the unseen world of those who sleep rough on the edges of Cape Town. Running to 290 pages, Solomon’s book is a lucidly fascinating immersion into the world of unlawfully occupied buildings. He takes as his area the ‘bad buildings’ that populate areas such as Hillbrow, Berea, the CBD, and Doornfontein (both New and proper). The book is divided into five parts, focusing on the many trials and tribulations of those who have made homes in parts of the city that have fallen into formal disuse, the poor of course being permanently condemned to the ranks of the ‘informal’.

As Wilhelm-Solomon explains, ‘many white residents and businesses chose, in the immediate post-apartheid period, to abandon the inner city for peripheral suburbs or distant countries, leaving vacant warehouses and residential buildings in rental and rates arrears’. The abandonment was a symbol of a way of life that no longer adhered, the former symbol of white might left open and defenceless. Travelling first with Médecins Sans Frontières (who were running an improvised clean-up scheme in the buildings) and then on his own, he makes acquaintances with the host of characters who make their dwellings in crumbling structures where water and electricity, security and wellbeing are in short supply.

The Blinded City is visceral in its insights, without simply becoming poverty porn. Roaming inside the dark, claustrophobic places, Wilhelm-Solomon meets the humans who are criminalised and vilified for ‘hijacking’, that most South African of sins. Many of those he meets are foreigners, travellers from countries whose borders are themselves legacies of different projects of white meaning-making in Africa. They seek better lives for themselves and their families, plotting out itinerant shelters demarcated by canvas and board, in the carcasses of old buildings. Sometimes the staircases are absent. Sometimes they burn down. The book goes to great lengths to illustrate the incoherence of the claim of illegality made against the varied groups of people who occupy the ‘dark buildings’ of Johannesburg. The hopes and fantasies of these groups are redirected and rendered precarious by the divergent and competing energies of the inner city. Looking down from a rooftop vantage point, Wilhelm-Solomon witnesses the contrast playing out:

In the neighbouring building, a group of men were dismantling the tin roof for recycling cash. One could see the city’s railway lines running to Soweto and beyond. Across the road was a polka-dotted apartment block advertising ‘trendy modern apartments’, from which one man on the roof told me he had been evicted. Nearby, one could see a mural from the recently gentrified Maboneng development.

Throughout this book, Wilhelm-Solomon is level-headed in his elaboration of these spiky contrasts—both serendipitous and malign—without elevating himself to the level of energetic lead performer. Where many Johannesburg texts are drawn to linger at the level of fascination with the seam-points where differences make themselves felt, this book patiently and journalistically follows people about. Many of the people are blind, an intriguing fact that lends the story its title. But the title also evokes the myopia that cities generate: each standpoint peers through a glass darkly.

The book is particularly intriguing when it engages why some buildings and not others become dark. Wilhelm-Solomon traces how the status of a building is often tied to the financial caprices of its owners. A death, or a sudden withdrawal of presence can signal that a building is up for grabs. Of one building, he observes:

… the Mozambican consulate moved out and the Bank of Mozambique—which until then had been managing the building—put a rental management company in charge. This company lost control of the building. The former caretaker, who had worked for the consulate, started to rent out the lower floors for his own profit. Other opportunists moved in, taking over floor after floor and charging illicit rental. The decline was rapid, and it was not long before Cape York became a dark building.

What The Blinded City highlights is that those who are forced by economic necessity to reside in the makeshift shelters offered by ‘dark buildings’ are often (but not exclusively) undocumented foreign migrants from Zimbabwe or Malawi. For the migrants of Johannesburg, the decade that falls within the book’s purview was marked by outbreaks of xenophobic violence, persecution tacitly or overtly enabled by the police, and picked upon by mercenary scoundrels posing as owners of the buildings in question. The book is really animated by its description of the long ongoing slog by destitute and displaced migrants to find a legal foothold in the city. These denizens eke out an existence where they are exposed to physical danger (at one point, we encounter a woman who has plunged through a hole in a building floor, breaking her arm), violence (including rape and murder), and the threat of being victimised by unscrupulous police or decanted into bleak deportation yards.

In post-apartheid South Africa, the migrant (whose illegality is a fact of inconsiderate law) is a scapegoat for all social ills, an easy blame to be revved up by political shills, greedy nationalist faux-kings, risible opportunist mayors and ministerial consiglieres, all of whom then visit their violence upon the undeserving who haunt the edges of the social. This exploitation community is aided in their ongoing efforts to destroy the poor by a veritable industry of securitising thugs with names like The Red Ants (infamous), the Bad Boyz (threatening) and the Black Bees (?!). Wilhelm-Solomon details how these dubious private armies, who treat the poor as though they are refuse, terrorise the inhabitants of targeted infrastructures at the behest of unseen overlords, often in violation of court orders that prevent unlawful removals: ‘Evictions were business’, the author notes. The terribleness becomes comic when after an altercation during which his phone is seized and he himself is roughed up, Wilhelm-Solomon finds himself chatting to one of his assailants, who asks him who he is:

He seemed genuinely curious. I was from Wits University, I told him, and asked if he was from the Red Ants.

‘No, I’m from Bad Boyz,’ he said. ‘I’m the baddest of the Bad Boyz.’

The metaphors proliferate. One senses that these adherents of scourging the impoverished imagine a Gotham-like retaking of the inner city from its (hazily defined) social ills. Once the buildings have been swept clean of the hordes, the elevators can be restarted and the modernist fantasy can be reasserted for good, deserving people, as defined by hedge-fund capitalists and fly-by-night housing consortiums. Where The Blinded City is at its strongest is that it doesn’t cast a horrified gaze upon the shattered atriums, cracked windows and vandalised interiors: it sees these things as symptoms of a broader social crisis. The analysis is undramatic and resists drawing big conclusions, preferring instead to let the story suggest its own contours. While another sort of book might have taken the de rigeur centre photos as an opportunity to present a lurid diorama of decay, Wilhelm-Solomon focuses on the people who give these buildings another sort of life, sharing in their small victories and the crushing tragedies of their lives. These are scenes in which the buildings that generate so much acrimonious squabbling, are shown to be what they are: places for living in, not collectables for acquisitive would-be property barons.

***

If this approachably panoramic book has a forebear, it is not another work of narrative non-fiction, but Louis Theroux’s beguiling 2008 documentary Law and Disorder in Johannesburg. Remembered more in today’s memetic age for introducing the world to the career criminal Maleven, Theroux’s film showed a Johannesburg inner city that, despite the efforts of a succession of shoot-from-the-hip mayors, remains intractable. In that film, the same Bad Boyz Wilhelm-Solomon encounters in his book are just beginning to get their spurs into inner-city security, and there is an intriguing contiguity between Theroux’s documentary and Wilhelm-Solomon’s book. In any event, both do much to suggest that the good old days will not return. The Blinded City exposes the state’s attempts to recapture the city as foundationless and unsympathetic to the actual situation as it is now.

We know that urban regeneration is a calumnious term when applied in a glad-handing fashion. It suggests that there is only value in economic movement, or rather, in the economic movement of the upwardly mobile. It is uninterested in the poor except as they might be strategically exploited (Ooh! Soweto bottlecap earrings!) and used as vibrant scenery. Johannesburg’s stylishly vacuous Maboneng precinct, which cynically or naively attempted to airbrush away the awkward clash of streetscapes in favour of banal bread-and-circuses for the middle classes, will go down in history as a brief false start in the slow regeneration of the city.

The salient aspects of The Blinded City lie in its keen attentiveness to the fact that a deeper understanding is needed, something other than contemptuous disregard for the desperately poor is required, if the problems of dereliction, inner-city housing shortages, and the need for social welfare are to be addressed. The property developers who vulture around the inner city, with their threats and their visions of characterless cleansed ‘accommodation’ are out of step with its rhythm. As Wilhelm-Solomon articulates, those who call the inner city their home have their own ways of being within the ‘volatile, violent and infinitely paradoxical place’ that is Johannesburg.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.