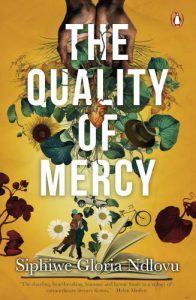

The JRB presents an excerpt from The Quality of Mercy, the new novel from award-winning writer Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu.

The Quality of Mercy

Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu

Penguin Random House SA, 2022

Read the excerpt:

The sky was filled with so many stars it shone when Spokes and the lovely Loveness alighted at Msimanga’s homestead. There was an entire group of people all waiting to receive her and welcome her back home. Their enthusiasm was tempered only by their open curiosity to know who the stranger unexpectedly thrust upon them was.

‘This young fellow followed our Loveness here all the way from the City of Kings,’ Msimanga said. Spokes thought he was joking and expected the people gathered around him to laugh, but they did not; instead, they all slowly arched one eyebrow—a family trait.

‘At least they are now coming from closer to home,’ a woman said matter-of-factly as she helped another woman to lift the trunk from the carriage.

‘Remember the young man who followed her all the way from Pietermaritzburg?’ another woman said.

‘That one was studying to become a lawyer. An African lawyer. Imagine that? What does this one intend to be?’ another woman said, looking Spokes up and down as she stood with her arms akimbo.

‘What do you know of studying?’ challenged a male voice from somewhere at the back. ‘You’ve never set foot inside a school.’

‘Is it any secret that I don’t have an education? It is because you are too content to do and say the obvious thing that your wife has once again become friendly with Sobantu,’ the woman with arms akimbo challenged back.

There were some scattered chuckles at this exchange even as a few voices told the woman she did not have to make things so personal.

‘Remember the man who followed our Loveness all the way from Johannesburg?’ another voice said, hastily changing the subject.

‘A poor mineworker, unfortunately.’

‘Much better than the one who followed her from Mafeking—a simple porter at the railway station, carrying things here and there and everywhere for the Europeans.’

‘I rather liked that one. He looked good in that uniform. Tall. The kind of tall that gives you confidence. This one is tall, too.’

‘Who cares for tall? Who cares for uniforms?’ the woman who was standing arms akimbo asked. ‘Our Loveness is educated. She deserves only the best of men.’

Spokes was confused. Were they having fun at his expense?

Msimanga looked at him and smiled. ‘You are not the first chap to come here wanting to marry our Loveness,’ he explained. ‘But you very well may be the last.’

Spokes was even more confounded.

‘Most of the time I am the one who has to invite the poor fellow—regardless of how flimsy his reason for finding himself amongst us is—to the homestead, but today our Loveness did that all on her own. So I would say that you, Spokes Moloi, stand a better chance than your predecessors.’

What was this? What exactly had he got himself into?

‘Now, although I am the headman in these parts, I am not very particular about the man that my daughter marries. I know that a young man—even one who has fought for the British in a war that was none of his business—can always build himself up. More importantly, I know that my daughter can choose wisely for herself, and if she chooses you, then so be it.’

Spokes did not know what to feel. All he knew was that when something seemed too good to be true … it usually was.

‘I will tell you a story,’ Msimanga continued. ‘After the story, I will ask you one question. Just one question. Then, I will let you sleep. First thing in the morning, I will ask you to answer the question, and if you answer it correctly, you can marry my daughter. It is that simple.’

There it was. The catch.

‘If you answer the question incorrectly, Raftopoulos, the Greek travelling salesman, will be here to fetch you first thing in the morning to take you to Krum’s Place, and we will ask you never to come back here under any pretext or pretence. Now, while all those who have come before you have failed, you should not take that to mean you will fail too—even if you did fight for the British in a war that was none of your business,’ Msimanga concluded.

After a hearty repast, everyone in the homestead, both young and old, gathered around the fire to listen to Msimanga’s story, even though it was obvious that they had heard it many times before.

The story went as follows. At around the time that the British were building the nearby dam, which was some twenty-odd years earlier, since it was also the time that Mazibuko, Msimanga’s wife, was expecting the child that would be Loveness, Msimanga’s best friend, Zwakele Mkhize, went to a beer drink one night and was never seen again—alive or dead. The best trackers were employed to look for him, and none of them found a trace that led to anything substantial. Expert help was needed and Msimanga himself sought the services of the best San tracker, but not even he could find any trace of Zwakele Mkhize.

To give context to the story, it had to be known that the Mkhize lineage had been given the chieftaincy by King Mzilikazi himself, but that because of Zwakele’s father’s enthusiastic prohibition of all things British in his village, the British were now looking to change the lineage from the Mkhizes to the Msimangas. It was true that Msimanga’s father had participated in the uprising against the British, but he had been charged with insurrection and had spent five years in prison, which had not only changed him, but converted him to Christianity and all things British. He had even gone so far as to have all his children, boys and girls, educated at the mission school that had been built near Krum’s Place.

The British liked how very … amenable Msimanga’s father had become, and when Chief Mkhize died, they took steps to change the lineage of the chieftaincy. Msimanga’s father, although not altogether averse to the proposal, felt himself too old a man to start learning how to rule a people, and put forward his son’s name in his stead. The British quickly corrected him, reminding him that it was the king in England who ruled the people, and that the headman’s function was merely to guide his people towards being better subjects of the king. Having said that, the British did not mind having Msimanga’s son as headman as long as he proved himself to be very like his father.

The British were pleased, the villagers less so. Their own king had, after consulting the ancestors, created the chieftaincy and chosen its lineage; as such, it was a sacred thing not meant for mere man to rend asunder. As much as they liked the Msimangas, the villagers wanted the Mkhizes to continue as headmen, and they made this very clear to the British.

This was exactly the kind of dogmatic traditional thinking that the British were trying to eradicate. They decided that instead of trying to reason with the villagers through verbal persuasion, which would probably prove pointless, they would build a dam instead—using labour from the village, of course—and show the villagers what the British could do for them.

Now, one would have thought that all this would have created a rift between the young Msimanga and Zwakele Mkhize, but their friendship—which had begun as most boys’ friendships did, when they were herdboys together—had proved to be made of sterner stuff. The young Msimanga made it very clear that it was not his intention to be headman, and the villagers appreciated his not wanting to change the status quo. But then Zwakele Mkhize disappeared, and the villagers had no choice but to allow the British (whose hand the villagers suspected in the disappearance) to have their way and instate the young Msimanga as headman.

Since the British did not seem eager to have the British South Africa Police (BSAP) investigate the case, Msimanga had done so instead, continuing to do everything in his power to find out what had happened to his best friend.

Here Msimanga’s story ended, and it was time for the one question to be asked: ‘What happened to Zwakele Mkhize?’

They all left iguma and retired for the night. Spokes was given his own indlu to sleep in, but even though he was lying on a well-made icansi and covered by a very warm ingubo, he had no other choice but to have a sleepless night as he tried to decipher the mystery. He had little hope that he could arrive at an answer that many before him, including a man training to become a lawyer, had failed to find.

Sometime during the night the most amazing thing happened. His mind started sorting through all the information it had received—the beer drink, the dam, the friendship, the trackers, the chieftaincy, the British—retaining what was important and discarding what was unimportant. How did his mind know how to do this?

It was only when he started rearranging the key elements into a connected and cohesive whole that he realised what he was doing. He was reconstructing the plot of a story, which was something he had done many times, with both oral and written stories. The only difference now was that the story that Msimanga had just told him was not made up.

His mind worked for most of the night until what had happened to Zwakele Mkhize was very clear to Spokes. The truth left him cold, so cold that even though he was covered by a warm and heavy blanket, he shivered his way through the early morning hours.

It was Msimanga himself who came to fetch him as the day broke.

Spokes found most of the homestead, including the lovely Loveness, waiting for him to either succeed or fail. Msimanga stationed himself and Spokes in the middle of the clearing, and everyone else formed a circle around them.

‘What happened to Zwakele Mkhize?’ Msimanga asked.

‘If you don’t mind, sir … is it possible, before answering, for me to ask one or two questions of my own?’ Spokes asked in return.

Those in the circle made noises, none of them particularly encouraging.

Msimanga looked at Spokes with his wise eyes and smiled his acquiescence.

‘You mentioned something about a dam being built around that time.’

‘Yes.’

‘At what stage was the dam?’

‘Completed, but yet to be filled with water. In fact, it was filled with water soon after,’ Msimanga said.

‘It began to be filled the very next day,’ a male voice volunteered.

‘Thank you. That is all I need to know,’ Spokes said before pronouncing, ‘Zwakele Mkhize is in the dam.’

Even though it had been obvious from his questions where Spokes was going, his declaration was met with a shocked silence.

‘You think someone pushed Zwakele into the dam?’ Msimanga asked.

‘I know so,’ Spokes said, before slowly adding, ‘and so do you, sir.’

The shocked silence was scandalised.

Finally an elderly voice from the circle asked, ‘What is this young man saying?’

‘He is saying that I pushed Zwakele into the dam,’ Msimanga replied, a smile on his face.

The silence became angry. Who did this young man think he was? What right did he have to say such things? The silence wanted him and his very dangerous ways gone, back to wherever he had come from … hopefully somewhere very far away.

But the silence did not belong to Msimanga, who simply asked, ‘How did you know?’

‘You said if I answered the question correctly, I could marry your daughter. But how—’

‘How could I possibly know what the correct answer was if I was not the one who had committed the crime?’ Msimanga concluded, impressed.

The silence decided to turn into a murmur so that it could have something to do, and would probably have carried on thus, perhaps infinitely, had someone—a woman—not had the presence of mind to enquire: ‘Why would Msimanga have all these people look for Zwakele if he knew that he …’ She lost her courage and would not finish her thought.

As it turned out, Msimanga had courage enough for all of them. His wise eyes looked very weary when he said, ‘At first I did it to ward off suspicion from myself … and then I did it because I grew tired of having got away with it. Another man’s death is a very heavy burden to bear. I thought that what I desired more than anything was the power that came with being your headman. It was only after Zwakele was gone that I realised that what I needed even more was a true friend.’

The silence wanted to be anywhere else but where it was.

Although Spokes had not spoken for quite some time, a man’s voice said, ‘This young man should shut his mouth! Shut up and leave our village this very instant.’

‘No. This young fellow has done the right and honourable thing,’ Msimanga said. ‘Imagine the bravery it has taken him to tell the truth with so much to lose. Imagine the integrity. Imagine the intelligence … I doubt our Loveness could find a man more worthy in whatever corner of the world she looks.’

The silence was not as convinced about Spokes’s virtues and attributes as Msimanga was. Spokes was lost in that silence until the gunshot rang out and alerted him to the fact that Msimanga had left the clearing and returned to his hut. After the gunshot, the silence turned into chaos that could not contain Spokes within it. In fact, the chaos made it very clear that it wanted him gone. So when Raftopoulos arrived to collect Spokes, the chaos unceremoniously ushered Spokes into the caravan. The last thing that Spokes saw as he was driven away was the lovely Loveness crying as she sat forlornly in the middle of the clearing. He knew then that bravery, integrity, and intelligence could certainly be costly possessions.

Once he was inside it, Spokes realised why Raftopoulos’s caravan could only accommodate one person. It was not so much that he had too many wares—bales of mostly second-hand clothing, stacks of threadbare blankets, mounds of blue and green soap, gallons of multicoloured oils, packets of cheap toffees and caramels, boxes of that greatest creation of all: condensed milk; it was that alongside all this and his own bedding, he had impressively crammed in the complete works of Charles Dickens. The leather-bound volumes were neatly piled on top of each other in an area so clean it could pass for an altar.

Spokes reached for the book at the top of the pile, A Tale of Two Cities, opened it and was shocked by what he saw—such a quantity of marginalia that he, who had never been permitted to make a mark of any kind in a book, felt it was a desecration. He looked at some of the notes, and they all were about how to properly pronounce words. So this was how Raftopoulos had taught himself to speak English, Spokes deduced, as he looked at the scribblings with a much kinder eye.

Once in Krum’s Place, Spokes was both surprised and pleased to discover that it was beautiful country with a river running through it—a river he could fish in the way his father had taught him. He saw himself happily settled there, and became convinced that, for him, Krum’s Place was the promised land. He would only fish again in that river; it would make the realisation of his dream that much sweeter.

Having found the land, Spokes made his way back to the place where the promise had been made: the corner of Lobengula Street and Selborne Avenue. The War Office where he had signed his name and joined the African Rifles had expanded over the years and now contained many offices, the smallest of which was set aside for returning native soldiers. It was in this office that he was told that Great Britain thanked him for his service but regretted to inform him that viable, commercial farmland had been set aside for returning British and European (but not German) soldiers and any British people who wanted to settle in the colony as they were the ones with the modern farming practices that would make the country a post-war agricultural giant. There was a proposed scheme to do the same for returning coloured soldiers, only on a smaller scale, of course: where Europeans would receive hectares of land, quite naturally, coloureds would receive acres of land. Perhaps a similar scheme, on a much smaller scale, could be proposed for the returned African soldier.

By the time Spokes left the office, he had talked the officer into holding out the possibility that in a few years, when the British had taken their fair share of the land, the returned African soldier would be able to occupy a few of the few remaining acres. He had even made the officer put his name—Spokes M Moloi—on a list, and was comforted and gratified by the fact that his name was at the top of the list, and that next to it were two words: Krum’s Place.

Disappointed but hopeful, Spokes left the minuscule office refusing to feel anger at the fact that the long-waited-on promise had not been kept. Anger at the British was what had made his grandfather not only fight in the First Matabele War in 1893 but also join the umvukela in 1896, which in turn was what had made the British hang him by the neck until he was dead.

The unpromised future that now stretched before Spokes presented few possibilities, the most practicable of these being training to become a teacher at the mission school that had educated him—an English teacher. This was his mother’s desire. She did not like the idea of her only child, a son at that, working in the City of Kings. All an educated African man could be in the City of Kings was a boy—a delivery boy, a messenger boy, a teaboy, a houseboy, a garden boy, a cook, a factory worker who was expected to do what the baas said and was never allowed to think for himself. She wanted greater things for her only child, a son at that. She wanted Spokes to be a man.

~~~

- Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu’s third novel, The Quality of Mercy, is out this month. She also is the author of the bestselling novel The Theory of Flight, winner of the 2019 Sunday Times Fiction Prize and currently a school set work, and its follow-up, The History of Man. A winner of Yale University’s 2022 Windham Campbell Prize, she is a writer, filmmaker and academic who holds a PhD from Stanford University as well as master’s degrees in African Studies and Film from Ohio University. She has published research on Saartjie Baartman and she wrote, directed and edited the award-winning short film Graffiti. She was born in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe.

~~~

Publisher information

This is indeed a story of mercy—and the redemption it offers. On the eve of his retirement, Spokes Moloi, a police officer of spotless integrity, investigates one final crime: the possible murder of Emil Coetzee, head of the sinister Organisation of Domestic Affairs, who disappears on the same day a ceasefire is declared and the country’s independence beckons. In following the tangled threads of Coetzee’s life, Spokes raises and resolves conundrums that have haunted him, and his country, for decades under colonial rule. In all this, he is staunchly supported by his paragon spouse, Loveness, and his unofficially adopted daughter, the unorthodox postman Dikeledi.

In her most magnificent novel yet, award-winning author Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu showcases the history of a country transitioning from a colonial to a postcolonial state with a deft touch and a compassionate eye for poignant detail. Linked to The Theory of Flight and The History of Man, Ndlovu’s novel nevertheless stands alone in its evocation of life in the City of Kings and surrounding villages. Dickensian in its scope, with the proverbial bustling cast of colleagues both good and bad, villagers, guerrillas, neighbours, ex-soldiers, suburban madams, shopkeepers, would-be politicians and more, The Quality of Mercy proposes that ties of kinship and affiliation can never be completely broken—and that love can heal even the most grievous of wounds.