Poli Poli by Barbara Masekela is a memoir that exemplifies the paradox of the ordinary and the spectacle in black women’s life writing, writes Athambile Masola.

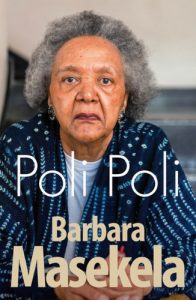

Poli Poli

Barbara Masekela

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2021

The autobiography of poet, educator, mother and activist Barbara Masekela, Poli Poli, is a collection of personal and political stories—which is to say, it combines quotidian family life with the spectacle of South Africa’s history. This balance is striking in three ways: the tensions between location and mobility; the stories of war and the effect they have on the women in Masekela’s life; and the inheritance of trauma as a result of apartheid and colonialism. These threads are then punctuated by delicate reflections on beauty, the simplicity of it, in the form of gardens, and the complexity of it, in the life of Masekela’s artist father.

Masekela’s memoir begins at home: ‘The only home I knew was number 76 Witbank Location. We called it KwaGuqa—the Place of Kneeling.’ This declaration immediately locates the story within a place and a people. Her home becomes a character, shaping the people and the childhood memories that are rooted there. It is a place marked by a history of dispossession and the growing antagonism of the nineteen-forties, which grows into full-blown apartheid policy as Masekela comes of age. In her home, language becomes the marker of the different mobilities present. Masekela’s ouma ‘speaks in Afrikaans, our home language, except when my cousins come to play, when we speak isiNdebele’. While this is not uncommon in black families, Afrikaans inside a black home has been an experience crowded out by narratives of it as the language of the oppressor rather than a language firmly rooted in black and Coloured family history. But Masekela does not belabour this linguistic heritage, and the nature of the legacy becomes clearer as the memoir unfolds.

While their primary home is KwaGuqa, the family’s mobility takes them to Alexandra township in Johannesburg, and Masekela’s education takes her as far as Natal, to Inanda Seminary, where she completes her high school, and Roma in Lesotho for university. The memoir ends with Masekela starting a new life in Ghana in 1963. The book is peppered with the names of places other family members live, pass through, settle and resettle. At the core of apartheid was control of the mobility and location of black people; however, this was not a homogenous experience. Middle-class black people such as Masekela’s parents were able to navigate the cityscape, given the nature of their work and their personal aspirations for themselves and their children. Masekela’s ease with the politics of mobility highlights the importance of particularities when recounting South Africa’s history, which is often caught up in grand narratives. In a sense, Masekela’s memories rescue the narrative of location and dislocation from becoming a spectacle of black life, by giving it the names and faces of people in her family.

Poli Poli is both a memoir and an ode to grandmothers, and Masekela centres the lives the women in her family, recalling:

My memories of childhood are of women in black. Picking up on scraps of their conversation, it seems that men disappear or die and women mourn and carry on. In my KwaGuqa family there are no grandfathers, only those sepia portraits of dead old men in severe Victorian suits caught by the cameras in a moment of ramrod posture with their unsmiling brides with distant looks. Their expressions symbolise the lot of women. They all look straight ahead.

Much of this lot looks like navigating life after surviving war, where villages have been replaced by farms and land is a commodity. It looks like brewing beer in the home to sell in pursuit of economic independence, in a context where ‘the presence of black women was an unintended consequence and a nuisance’. This is the world Masekela’s grandmothers create and recreate, through friendships and community building, after childhoods marked by being ‘attached to Dutch households as child domestic servants’.

Masekela’s lyrical writing captures the depth of the suffering her grandmothers lived with, even as they tried to keep the children away from stories of the past. Trauma and tragedy are part of the inheritance of colonialism and apartheid, and this inheritance is lived out in the everyday, through simple, taken-for-granted habits.

Masekela explains:

For all the grannies, nostalgia drips blood. The early past is rarely referred to and the meagre snatches of remembered episodes of racial abuse and brutality are summarily halted when we children walk into the room. So, we learn to live without being caught. We become detectives in search of what they have lost—this is no longer tangible but it hangs about in the curtness of their answers and the softness of the cheap cuts of meat they boil then brown with onions for gravy. Their conversations are meagre, interposed with recitals of the quality of their sleep, who of the dead visited them in last night’s dream, our behaviour, white men and the weather. They create riddles that are yet unravelling and still confounding. Their memories are cut-up heart strips, Humpty Dumpty pieces they do not want to put together again. What they have seen, felt and heard is unspeakable.

I quote this extract at length as it demonstrates the ways in which children of survivors learn that they have to pay attention if they are to catch snippets of stories from the past. These stories are not easily available, they live in and among the children and their grandmothers in their everyday life, and watchfulness, too, becomes part of a colonial inheritance. Masekela’s attentiveness is akin to the instinct described by Alice Walker in her essay ‘In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens’; one that imagines what it meant for black women to be artists and creators during slavery, looking beyond the pain of repressed imagination: ‘But this is not the end of the story, for all the young women—our mothers and grandmothers, ourselves—have not perished in the wilderness.’ As even though Masekela grows up keenly perceptive of fragments of pain and nostalgia, she also grows up attentive to beauty.

Masekela’s father was an artist, ‘mad for beauty’. He created it through gardens and sculptures. This form of expression meant that pain lived alongside loveliness. But the ability to create beauty in a life filled with strife was a humanising experience, which resisted the apartheid reality that sought to shrink the imagination. Masekela explains that her father’s aesthetic ‘was always reaching out to something higher, something he would never find in the world in which he had chosen to live’. Her father’s insistence on creating art in spite of the distractions and disruptions of apartheid is not without bitterness, as he received little recognition while he was alive. Maskela’s resentment is palpable and justified, as she wonders ‘what would have happened to his contemporaries, like Villa, Skotnes and Preller, had they been born African … I wish he had been angrier about it …’

While Masekela is able to write about her father, her brother, her lovers, her uncles, some of the men in her childhood are victims of tragic deaths in their youth. Here, again, her writing does not shy away from trauma but rather draws us in, begging that we truly understand the nature of a conquered people. In a chapter dedicated to ‘Uncle Bower and the Men of Witbank’, the men who survive death and live as breathing, laughing humans in Masekela’s childhood are a mixture of those traumatised from fighting the ‘white man’s war’, those who spend their afternoons drinking in Ouma’s kitchen, the uncles and brothers who come and go through the family home, the scoundrels in Alexandra who harass young women. There are also the young white men responsible for the death of her mother’s elder brother, Uncle Bower. This range of identity invites readers to consider the ways in which masculinities can be historicised even as we confront the toxic versions that have the ability to reproduce themselves through initiations of violence.

As part of the rich legacy of black women’s life writing in South Africa, Masekela’s Poli Poli joins the chorus of voices that includes Noni Jabavu, Ellen Kuzwayo, Fatima Meer, Brigalia Bam, and many others. Women who wrote their own stories, and in so doing wrote the histories of their families and communities, narratives that are often undermined in mainstream history. These community and family histories broaden the vision we hold of ourselves. Masekela herself reflects on how she is a part of all the people she has met:

I am Jwana as I am Kenneth as I am Rakgadi Mokonye, whom we called the Sphinx. However, with the help of experience and unplanned encounters, I am also the girl from Haiti with the green eyes and the blonde, kinky hair who was mother to my son, Mabusha, in LA. I am Krotoa and Mmanthatisi and Delilah and Auntie Pixie …

Every time a black woman writes their story they are resisting marginalisation, they are creating more space for black women’s voices to be taken seriously. In Poli Poli, Masekela has carved out a space in her political life that continues in her literary life.

- Athambile Masola is writer, researcher, lecturer and award-winning poet. Her debut poetry collection of poetry in isiXhosa, Ilifa, was published by uHlanga Press in 2021. She is the co-author of the Imbokodo: Women Who Shape Us series (Jacana, 2022). She teaches in the Department of Historical Studies at UCT. Follow her on Twitter.

Brilliant review of a brilliant book!