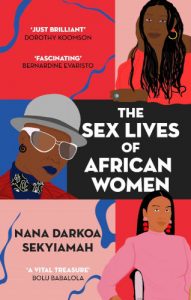

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah’s The Sex Lives of African Women is an important addition to writing that resists the fetishisation of Black women’s experiences, writes Fungai Machirori.

The Sex Lives of African Women

Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah

Little, Brown, 2022

Many years ago, I attended a bridal shower that has continued to be informative to me about how women within my African context, Zimbabwe, generally discuss sex and sexuality. The bride-to-be, a young woman in her twenties, was visibly pregnant. And yet, there was an insistence among the all-female group in attendance to offer her advice on how to handle her ‘first’ sexual encounter, which popular consensus had made clear would only occur on her wedding night. Granted, there were older women in attendance which—as per the tenets of cultural modesty and respect—made the discussion more difficult. But even after they had left, the reticent mood continued.

Talking candidly about sex and sexual pleasure, even within women’s safe spaces, can often be met with prudishness and sometimes even embarrassment. And this is why The Sex Lives of African Women, the debut offering by Nana Darkoa Sekyiamah, is an invaluable contribution to writing about African women’s sex lives.

The anthology contains thirty-two women’s stories, including Sekyiamah’s, collected as interviews over five years, between 2015 and 2020, from women aged twenty-one to seventy-one, and from thirty-one countries across the world. The reader is introduced to a range of women; to fifty-two-year-old Miss Deviant, who is a Black lesbian and part of the bondage, domination, and sadomasochism (BDSM) subculture as a dominatrix, as well as thirty-six-year-old Shanita, who reflects on her almost thousand-day-long celibacy and how she is tapping into her sexual energy to manifest her wants and desires. The book is organised in three parts, self-discovery, freedom and healing, with each section providing thematic reflections.

At the start of reading the collection, I worried that the narratives would become monotonous and that I might become disengaged. But there is such rich diversity in the sexual experiences documented that every story offered something distinctive and thought provoking. This is testament to the care taken by Sekyiamah to engage with different African women’s voices and experiences. Each story is written as a vignette offered by the contributor in the first person, some being musings about past sexual relationships, others reflections about ongoing relationships and encounters. As one contributor, Bingi, notes, ‘Sex can help you figure out the type of person you are. Sex has definitely helped me know myself.’

Sekyiamah weaves her own story into the collective narrative, introducing each contribution with some context around how she met the interviewee and sometimes illustrating how their story resonated with her own. The final chapter of the book is her narration of her own story, expanding on the parts of which she shares throughout the book. And she meets her interviewees in so many different and sometimes serendipitous ways; at a club, at conferences, through mutual friends and via social media calls for participation. For one interview, Sekyiamah makes contact with the contributor while on holiday in São Tomé and Príncipe, striking up a conversation with a tour bus guide who then introduces the two to each other. The reader is thus presented with contributors from diverse and occasionally unexpected parts of Africa and the African diaspora, such as Bahia in Brazil, or Haiti, Barbados, Costa Rica.

What results is a political body of work that broaches different kinds of sex (masturbation, cybersex, sex work) within different contexts (celibacy, monogamy, polyamory, open marriages, BDSM, with disability) and across the spectrum of sexual identity (lesbian, queer, trans, bisexual, heterosexual). One story also discusses FGM/C, female genital mutilation. The women interviewed allow themselves space to explore who they are becoming and identify as they are comfortable; for example as a ‘married, polyamorous, pansexual African woman’, as one contributor, Helen, describes herself. Hers is an intriguing story about how she and her husband have opened up their marriage, exploring swinging and kink along the way. ‘Opening up our marriage,’ she says, ‘has made a huge difference to the relationship my husband and I have. I’ll always love him but I have no expectations that he or anyone else can meet all of my needs.’

Themes of gender-based violence recur in the book, reflecting the patriarchal environments that African women still have to navigate. At least ten of the stories begin with a warning that the story contains experiences of either rape or sexual assault, or both. Out of the thirty-two stories, that roughly represents one in three women—echoing the often quoted statistics about women’s exposure to sexual violence. And while these narrations are harrowing to read, they provide important context, as many African women will be familiar with experiences of non-consensual sex and sexual acts. Patriarchal double standards also show up in some of the narratives that speak to sexually liberating experiences. Miss Deviant, for example, reflects on this in her experiences as a dominatrix: ‘I had an awakening in the last three to four years about being a woman in this world. I realised that male submission is bullshit. Men can dip into it but when they go out into the world they are not advocating for equal pay.’

The stories candidly convey intimate details of personal joys, fears and vulnerabilities. This openness is not surprising given Sekyiamah, as interlocutor and co-storyteller, has been publicly discussing sex and sexuality for over a decade. She is the co-founder of the blog Adventures from the Bedrooms of African Women, where African women have been blogging about their sexual experiences since 2009, and has also written frequently and candidly about her own sex life there.

Sekyiamah acknowledges that had the blog not existed, it’s likely the book would not have emerged. ‘It’s through the blog that I knew that there were many fascinating stories out there,’ she tells me. ‘That was the impetus for me to think to interview a whole bunch of African women and write a book about their experiences.’

Apart from one contribution by a South African woman of south Asian descent, all the other stories shared are from Black women. As one contributor, Alexis, observes, ‘Black people are not often invited to identify themselves as “hedonistic” or deeply in our bodies.’ I asked Sekyiamah why this focus was important.

‘The politics behind this was wanting to show that our experiences are varied and that we come from different sexualities and gender identities,’ she says. ‘I felt like there are some books that exist that focus on white women’s sexuality, but none that exist that focus on African women’s sexuality.’

Just as important is that the collection is authored by a Black African woman. Sekyiamah believes that had the book been compiled by someone who wasn’t Black—and feminist—it would have been a very different collection, and may have run the risk of exotifying Black African women’s sexuality. The Sex Lives of African Women, therefore, is not only an important collective political work in which Black women push back against the omission of their voices in popular discourse around sex and sexuality, it is also an important addition to writing that resists the fetishisation of Black women’s experiences.

Diaspora is an equally important political underpinning of the book. In its Preface, Sekyiamah states that as a Pan-African feminist it was important for her to include the experiences of Black women displaced from the African continent via slavery and colonisation, as well as those who have voluntarily migrated.

The effects of Covid-19 are also chronicled, and some interviews had to be conducted via Zoom or social media as a result of global lockdowns. At the same time, the pandemic caused some contributors to work through the disruptions to their sexual relationships that Covid brought with it. Sekyiamah says that she doesn’t think the stories shared virtually are any less rich than those that were conducted face-to-face—in fact, interestingly, she feels the pandemic may have helped her complete the book in a timelier fashion.

The Sex Lives of African Women is an important contribution to Black African women’s life writing, showing them in all their vulnerability and strength. With Sekyiamah already having set a precedent for African women’s online public discussions around sex, it is truly a delight to see her continue this exploration in a format that is likely to reach even further audiences.

- Fungai Machirori is a Zimbabwean writer, researcher and commentator interested in African literary and digital spaces. You can learn more about her work at her website.