The JRB’s Editor Jennifer Malec chats to Joanne Joseph about her debut novel, Children of Sugarcane.

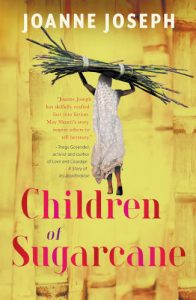

Children of Sugarcane

Joanne Joseph

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2021

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: Your book Drug Muled, which came out in 2013, was a bestseller, but this is your debut work of fiction. Was it that first book that indicated to you publishing was an achievable goal? Or did you have fiction writing aspirations when you grew up?

Joanne Joseph: I enjoyed writing as a child, but never imagined that I could write anything publishable as an adult. Even when I was studying literature and working in the media, I saw myself very much as a consumer of books rather than a creator of them. Drug Muled was the result of an intriguing long-format news interview I did with Vanessa Goosen, after which the strands of her story began to weave themselves into my thoughts. I began to wonder whether I might have the ability to turn those thoughts into a book. I knew it would likely have to fall into the genre of creative non-fiction, which was particularly challenging for someone who wrote news scripts for a living. But I realised in the translation of that narrative onto the page that there was a real freedom in working outside of the stringent writing boundaries I had set for myself—that perhaps I had compartmentalised myself too much as strictly a news and current affairs writer—and there was also far more I wanted to and could say, outside of the platform on which I was broadcasting daily. So that first book was really a writing test for me, and when it was published, I felt I had ticked one small box but was keen to try to challenge myself with a more difficult project in the future.

The JRB: In his praise for Children of Sugarcane, Imraan Coovadia calls it ‘a novel of the old kind’, which must have been very gratifying. Do you think this description fits? Is this something you were going for? Who are your literary influences?

Joanne Joseph: It was very kind of Imraan to endorse Children of Sugarcane. While it’s impossible to explain his exact thinking, I infer that he was referring to the genre of historical fiction through which the novel embraces the past, its vestiges, memory and the act of memorialising. All of these elements are quite central to the novel. In terms of influences, I read a huge variety of literature including a range of non-fiction political and sociological analysis, academic articles, particularly on the subjects of feminism, gender studies and critical race theory. In terms of fiction, I enjoy historical, contemporary, speculative, science and crime fiction as well as magical realism. It would be difficult to limit myself to a short list of favourite authors.

The JRB: More on that later! Children of Sugarcane was inspired by the life of your great-grandmother. What was it like getting inside the mind of a young woman from rural India in the eighteen-hundreds?

Joanne Joseph: The key to finding that interiority didn’t lie in the most obvious places. I found a picture of my great-grandmother, Athilatchmy Velu Naiken—just one surviving photograph of her, which I treasured. And I spent ages staring at it, as if she had the power to speak to me through time. But I never learnt how to discern her gaze, and I realised that no matter how hard I tried to recreate her, too much of her story had simply been dissolved in the passing of time for me to do justice to any accurate description of her life. What I felt I had to do was create a character who carried within her some of Athilatchmy’s DNA—or at least, what I gleaned about her: her courage, her resilience, her stoicism and what I read as her streak of rebellion too. I explored her environment as a rural, lower-caste Indian woman in the eighteen-hundreds, the political, cultural, religious and social constraints of the time, compounded by geographies and climate. The archives and a wealth of documented history, courtesy of the painstaking work of many brilliant academics—in particular, South African ones—opened a window into this world for me. And then I began to ask the question: how would any woman of this background respond to the myriad influences and the burdens pressing down on her? Children of Sugarcane is the answer to that question.

The JRB: Could you talk a little bit about how you went about researching this novel? I’m thinking specifically about the kinds of personal stories you must have drawn on, and where you found them?

Joanne Joseph: Inside Indian Indenture—a wonderfully collated historical work on indenture by Ashwin Desai and Goolam Vahed played a pivotal role in painting the human face of indenture for me. Many of the events documented in this book found their home in some form in Children of Sugarcane. Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie’s From Canefields to Freedom offered a beautiful pictorial record of the lives of the indentured. In this vein, literary academic Betty Govinden, a beloved mentor, shared with me pictures of the ruins of a tea factory in Kearsney where her grandmother was indentured. Selvan Naidoo and Kiru Naidoo, through the 1860 Heritage Centre, wrote extensively on the harrowing voyages Indian labourers undertook to come to the Colony of Natal bringing home the horrors of that experience, while Zainab Priya Dala’s What Ghandi Didn’t See compelled me to meditate on notions of intergenerational trauma, silences and changing notions of Indianness. These are a few of the main influences on the novel, but there are many more.

The JRB: Turning to the novel itself, do you think Shanti would have had the wide life experiences and resilience she had if she hadn’t had the benefit of a secret education as a young girl?

Joanne Joseph: I doubt she would’ve had such varied experiences. For one thing, she would’ve been geographically confined to what is now Tamil Nadu. I think Shanti demonstrates that one of the most powerful tools education gives us is a sense of how vast the world is, so we begin to imagine all the possibilities emanating from our place in it. Once education opens Shanti’s mind to this, she becomes impossible to cage. But as resilience goes, who knows what level of resilience she might have had to develop to survive a violent marriage or fend off the effects of colonisation in India had she remained there as a teenager? My sense is that any of these variables might have demanded the same or more resilience of her.

The JRB: At the book’s launch in Sandton, Iman Rappetti asked people to raise their hands if they had ancestors who came from foreign places, and the majority of the audience did. In a way, the story of travelling to South Africa is an archetypal South African tale. Why do you think it’s important for these stories to be told?

Joanne Joseph: You’ve touched on something so important there—the stories of migrancy, whether they’re the tales of Africa’s people moving through her or the arrival of settlers who have become Africans over the centuries. I look at the increasing xenophobia in our country, which is taking a disturbing turn, fuelled by opportunistic politicians. The narratives they propagate fail to recognise migrants as fellow human beings fleeing grave difficulties of one kind or another, whether it’s conflict, economic collapse, lack of educational opportunities, unemployment or hunger. Does anyone willingly choose to cross crocodile-infested rivers or climb into an overloaded rubber dinghy with their children, clinging to the hope of reaching the other side alive? Literature is one of the most powerful ways of building empathy in human beings because it brings us face to face with the experiences and suffering of others. It has an important role to play in restoring the humanity of those we’ve robbed of it in real life, including South Africa’s migrants.

The JRB: At the launch you also spoke about how at times you had to write through tears. With such harrowing subject matter, so entwined with your own history, was it difficult to focus on the nuts and bolts of the novel? How did you combine the emotional process with the mechanics of writing?

Joanne Joseph: Getting that first draft of the emotionally challenging chapters down was always especially demanding. You are not only processing what is happening to your characters, you are all too aware that you are simulating what happened to real people and that’s a searing thought. But to my mind, that’s exactly what my first draft ought to be, a vomiting onto the page of my angst as a writer tackling arduous subject matter. In the weeks that followed, I’d reprocess those chapters differently after having come to terms with the content. I’d start paying more attention to word choice, dialogue, sentence structure, characterisation, plotting and all the technical aspects that go into crafting a chapter. I think writers approach this kind of subject matter differently, but that was how I got through it.

The JRB: In your note at the end of the book, you write about how it had ‘undergone multiple incarnations’ in the nine years it took you to complete. How did the book change, and how much did it change?

Joanne Joseph: Over a period of nine years, I changed and the book changed as a result of that. During those nine years I got married, had a child and began learning about marriage and motherhood. I took on demanding broadcasting jobs that required me to develop myself in new ways. My parents were growing older and my mom was briefly very ill but thankfully pulled through to see her granddaughter and help raise her in the early years of her life. I saw very little of my brother who lives overseas, which was tough because we are very close. I don’t think it’s really possible to undergo these life challenges and not reflect that in your writing. A lot of writing is learning—it’s growing to understand yourself, your ambitions and desires, how you manage your relationships, enjoying the invitation of human beings into your inner circle who are quite different to you culturally or otherwise, but through whom you begin to see life through a multitude of diverse lenses. Why wouldn’t you imbue your characters with some of that knowledge even if they do exist in a different time? The fact of being human has probably changed little over the centuries. So, if I go back to those earliest drafts, they are cumbersome and embarrassingly overwritten. But I’m reminded that there are no dramatic plot twists I introduced over the years. What changed was my style of writing, the manner in which my characters resisted the oppressive system of indenture, the way they interacted and understood one another, the discoveries they made about love, survival, friendship and sacrifice in cruel circumstances.

The JRB: It’s often said that one of the more challenging aspects of writing historical fiction is how to wear your research lightly; how to decide what to leave out. Can you talk a little about how you approached this?

Joanne Joseph: This was one of the largest stumbling blocks in my earliest drafts. I was presenting an extended history lesson rather than a historical novel, which you’re inclined to do after spending months and months researching a topic widely and feeling like you don’t want to ‘waste’ a smidgen of all the reading you’ve done. But critically reading the works of other writers gradually taught me how to nestle history within the folds of my narrative. Just one example of this: I remember reading Ama by Manu Herbstein several years ago and realising, this why he succeeds as a historical fiction writer: his protagonist is so human—a woman the reader can really care about and emotionally invest in; the setting in the time of slavery is epic. He has worked at it like a set painter, sketching it as so vast a backdrop, that the reader never loses the sense for one moment that Ama’s entire life exists against this skene; yet history does not live only in that backdrop, it comes alive in all the minutiae like the food, the clothing, the language and the customs of the time, making the tiniest details important. These observations became extremely useful to me.

The JRB: Running through the layers of research, and at its heart, is a well-constructed plot—I must admit I was glued to the page as the final twist unfolded. How far into the writing process was your plotline settled? Did you play with different versions?

Joanne Joseph: I did play with a few versions. I remember a long conversation with my husband one night in which we lay in the dark and pored over the possible outcomes before I had got much writing done. At issue was which characters should survive and which shouldn’t. I had a very fixed idea at the time of who was going to live and die. He disagreed. Needless to say, his version stuck and I found a way to make it work!

The JRB: Shanti says to herself: ‘Secrets are like wild birds. They cannot be held captive forever.’ The implications of this idea are very interesting. Secrets of the kind revealed in this novel may be shameful and painful, but here we learn that they can also be also beautiful, vital, vivid. Would you agree?

Joanne Joseph: At times, societal conventions dictate that we keep parts of our lives hidden to avoid the burden of shame. As a woman of that time, how would Shanti have explained her daughter’s existence in a manner that would satisfy her community’s cultural norms? How would this revelation have affected her daughter, Raksha? How would Raksha, in turn, have overcome her secret shame if news of it had been publicly revealed? In this novel, I’ve stubbornly compelled the characters to face the revelation of secrets they don’t initially want revealed and the accompanying repercussions. But once this is done, it allows them the freedom to eschew the societal constraints which have forced them to conceal their truths in the first place.

The JRB: The novel tells the story of the cruel and patriarchal world of the British-owned sugarcane plantations of Natal, but it is also concerned with the deeply personal: love, friends, family. I feel these details, as Raksha finds in Shanti’s writing, are ‘the nuance of light’ that complicates the ‘black and white’ of our colonial history, that makes us think more carefully and subtly about our history.

Joanne Joseph: Indeed. In the course of understanding how human beings navigate difficult times in history, it is pivotal to explore ways in which they seek to assert their humanity and foster their joy in defiance of the subjugation that marks their lives. Not every character in a novel of this nature is going to be a vociferous freedom fighter, for example, but that does not mean they don’t engage in acts of subversion which carry within them the seeds of heroism. In Children of Sugarcane, this is partly how the characters entrench their sense of self in a context in which their identity and culture are deeply compromised and their personal histories are all but erased. It is the love, friendship and mutual support that both sustains them and becomes the small, individual acts of protest against a system that is designed to deprive them of all happiness.

The JRB: No spoilers, but I was very sorry to say goodbye to Mustafa two-thirds of the way through the novel. So I was quite pleased by developments at the end. How does it feel to leave these characters behind? Will we see a sequel?

Joanne Joseph: Mustafa really seems to have grown on many readers! In some ways, I have given these characters an imagined ending that I have left up to the reader to decide. Several readers are demanding a sequel, but I don’t think I want to go there. Children of Sugarcane feels to me like it should be a standalone novel. I haven’t entirely left these characters behind, though. They lived in my head for nine years and spoke to me often. Although they’ve since moved out, I still think of them lovingly and am grateful for how warmly they’ve been embraced by generous readers.

The JRB: Finally, since writers are often great readers, we like to ask: what have you been reading recently that you would recommend?

Joanne Joseph: This may not be everyone’s cup of tea because the subject matter is quite sombre. But I have truly been relishing the artistry of Our Ghosts Were Once People, edited by Bongani Kona. The collection brings together brilliant writing on death, dying and grief. It must be some of the rawest and most nuanced writing to come out of South Africa in recent times.

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor. Follow her on Twitter.