The JRB presents an interview with Siphiwo Mahala about his new play, Bloke and His American Bantu.

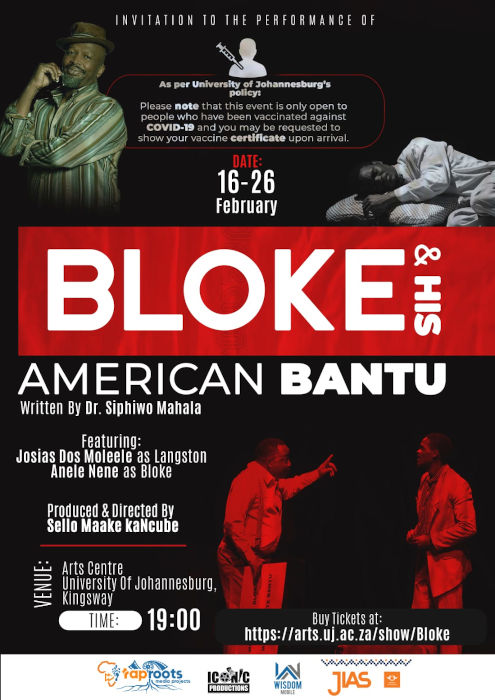

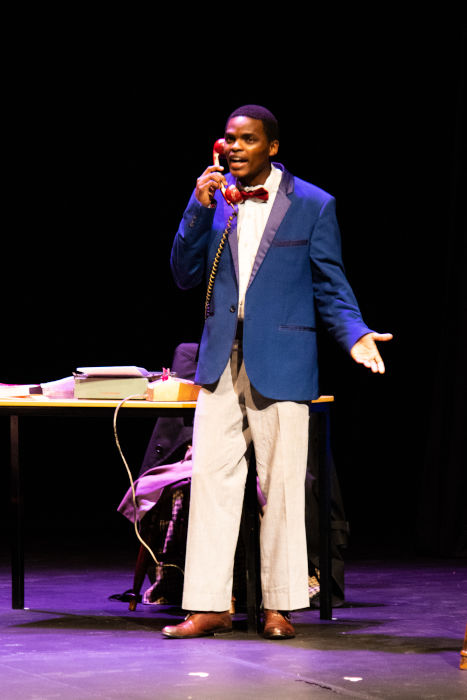

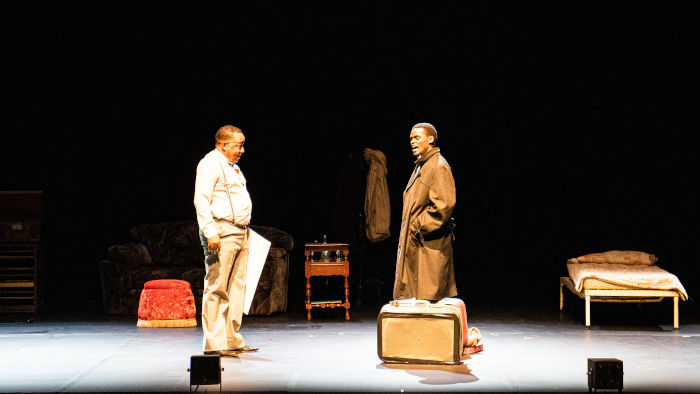

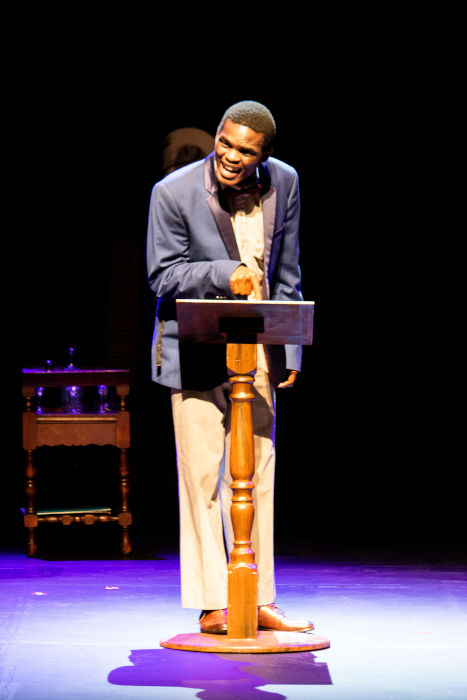

Bloke and His American Bantu is produced by The University of Johannesburg in association with the Sello Maake kaNcube Foundation, directed by the internationally acclaimed Sello Maake kaNcube, and stars Anele Nene as Bloke Modisane and Josias Dos Moleele as Langston Hughes.

Bloke and His American Bantu will be on stage at the UJ Arts Centre in Johannesburg from 16 to 26 February 2022 at 7 p.m. every day, except Sunday and Monday.

The JRB: Congratulations on the production of Bloke and His American Bantu, Siphiwo. Tell us a little about the inception of this play. Where did the idea come from?

Siphiwo Mahala: Having read quite extensively about the Harlem Renaissance, and knowing that Langston Hughes had corresponded with Es’kia Mphahlele, I was always interested to see the original letters. When I visited the United States for the first time in 2012, I went to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, New York, where Hughes’s ashes are buried. The next day I went to the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library in Connecticut, where Hughes’s archives are kept. Here, I found the correspondence with Mphahlele, but more than that, I realised that there was reference to Bloke Modisane in almost every second letter. When I asked for the Modisane files, I realised that Hughes had a much more intimate relationship with Modisane compared to many other people he corresponded with throughout the world. They wrote to each other frequently, exchanged intellectual banter, confided in each other, and at times wrote to each other for the sheer joy derived from the art of letter writing. I could visualise their lives unfolding right before me as I was going through the letters. A play was born.

The JRB: The play is set in the nineteen-sixties, during, as you say ‘one of the darkest hours in the history of South Africa’. Why do you think this is an important story to tell in South Africa in 2022?

Siphiwo Mahala: It’s an important story to tell, first of all, because it’s a uniquely South African-American story. In other words, South Africa has staged many American plays to which we can relate and from which we can model our lives. This play is about our joint heritage. It is not an American story put in the context of South Africa. It is a story that illustrates the ties that bind South Africa and the United States of America. It shows the role of cultural workers and intellectuals in the fight against apartheid. It demonstrates how important the cultural sector was in mobilising international solidarity against apartheid. Most importantly, it shows us that artists have the agency to build relations between nations beyond what diplomats can ever dream of. Following the Sharpeville Massacre, the world’s eyes were on South Africa. Modisane, who had writing credits alongside Lewis Nkosi for Come Back, Africa, a film that came out in 1959 and gave Miriam Makeba international exposure, used his cultural agency to conscientise the world about the sociopolitical condition in South Africa.

The JRB: This is a story of solidarity across borders, one that highlights the value of these kinds of relationships between artists and intellectuals. What do you think the two learnt from each other intellectually during their conversations?

Siphiwo Mahala: Bloke Modisane had been following Hughes’s work for years, and being published by him in An African Treasury in nineteen-sixty was a major breakthrough for Modisane into international markets. Similarly, until Hughes was introduced to the Drum writers like Henry Nxumalo, Can Themba and Modisane, the only South African writers he had read were Alan Paton, Nadine Gordimer and Peter Abrahams. Publishing the book gave him exposure to the work and thought processes of a kaleidoscope of African writers.

Hughes came from a mixed family background, and was deliberate about reclaiming his black identity. However, apart from a number of short visits, he had not lived on the continent. Through the exchange of letters and gifts, including cultural garments, as well as learning some isiZulu and Sepedi words, he was learning the tenets of blackness from Modisane. Similarly, Modisane delivered over twenty lectures across the US, in which he shared the living experience of black South Africans in a country where they were an oppressed majority. His lectures in the US were not just political, he taught African rhythms in music and dance, among other subjects. In a sense, through Modisane, Hughes learnt what it meant to be a black South African banished from your ancestral land.

The JRB: What personal aspects of the letters between Modisane and Hughes were you keen to bring out in this work? In other words, what about their relationship and camaraderie touched you and inspired you to share this story?

Siphiwo Mahala: What struck me at first was witnessing the evolution of their friendship, to see them addressing each other innocuously, and then getting to know each other, becoming nonchalant, giving each other affectionate names and exchanging banter. I also found it amazing that at some point in the nineteen-sixties, they sent each other several letters within a space of a week. It came naturally that, when one was in trouble, they knew whom to call and the empathy was palpable even though they were separated by the Pacific Ocean. When Modisane was destitute—unemployed and homeless in London, and even contemplating going back to South Africa where at least he ‘was alive’, it was Hughes who lent an ear. Similarly, when excited over something, they wanted to tell each other about their fortune and celebrate together.

The JRB: The conversation between these two men highlights the differences and similarities that connect the South African liberation struggle with that of Black America. What struck you about this connection as you were reading and writing?

Siphiwo Mahala: The similarities have been written about—being that black people were oppressed and discriminated against in both countries. Parallels have been drawn between what are popularly known as the Harlem Renaissance and Sophiatown Renaissance; similarly, connections have been drawn between the Black Power movement in the US, and the Black Consciousness movement in South Africa. Black people in these two countries fought similar struggles. However, there are two major differences: the first being that apartheid was legislated in South Africa whereas discrimination was not necessarily an official government policy in the US; the second is that black people in South Africa, unlike the US, were the oppressed majority. These are some of the scenarios that are explored in the play, and I think more than the historical facts, there is a special emotional connection that the peoples from these two nations share, and this comes strongly in the play.

The JRB: What approach did you use to get into the mind of these two men, who lived at a very different time to you?

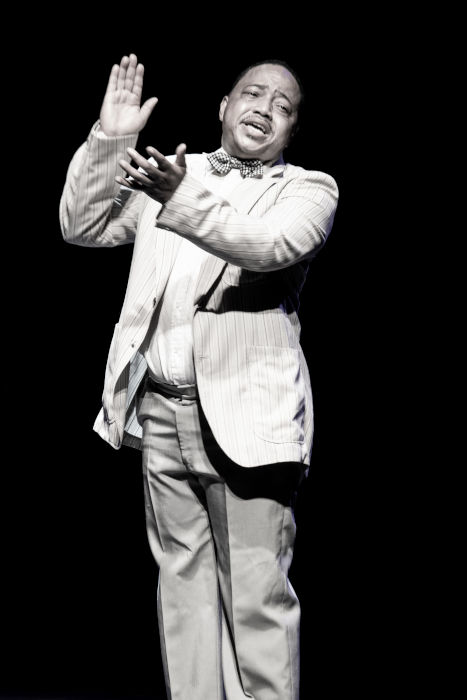

Siphiwo Mahala: I read over fifty letters exchanged between the two, and there was no way I wouldn’t get to understand who they were, their anxieties and ecstasies. Furthermore, I spent nine years reading further on them, watching documentaries and reading their work. I visited New York at least four times in the past ten years. I spent a lot of time researching before I could sit down and write. This helped me a great deal in portraying their characters. I was fortunate that Sello Maake kaNcube, the director of the play, immersed himself in the work and helped the actors understand and feel the story as opposed to just memorising the words. The two actors in the show, Anele Nene and Josias Dos Moleele, do great justice to the characters.

The JRB: Do you have a favourite piece of Modisane’s writing? What about a favourite Hughes poem?

Siphiwo Mahala: After going through all their writing as a researcher, I find it hard to decide on a single piece of writing as my favourite. What stands out for me in terms of significance is the opening lecture Modisane delivered at the American Society of African Culture (AMSAC) authors’ dinner in March 1963, titled ‘Short Story Writing in Black South Africa’. It set the tone for his US tour, but it’s also about short stories, which is my area of specialty. Similarly, I think with Hughes ‘The Negro Speaks of Rivers’ holds a special place for me because it’s a poem that ushered him into superstardom when he was only seventeen years of age.

The JRB: Thank you for your time ahead of the play’s premiere.