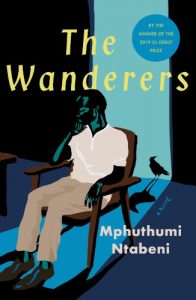

Mphuthumi Ntabeni’s The Wanderers is a novel that indicates a storyteller in love with the art of telling tales, writes Joanne Ruth Davis.

Mphuthumi Ntabeni

The Wanderers

Kwela Books, 2021

The Wanderers is the second novel from Mphuthumi Ntabeni, whose literary talent was thoroughly showcased in his historical work The Broken River Tent, with its haunted exploration of unsung nineteenth-century Xhosa history and its impact in twenty-first century South Africa. That novel won the University of Johannesburg Debut Prize for South African Writing in English and was longlisted for the 2019 Barry Ronge Fiction Prize. In The Wanderers, Ntabeni has once again presented us with a busy, populated and innovative novel that will likewise make a telling imprint on South African historical fiction.

The Wanderers is a distinctly Pan-African novel, set in South Africa and Tanzania, with nods to Zimbabwe and Rwanda. Phakamile ‘Phaks’ Maseti and his daughter, Ruru, are driven by the destiny of the Mfecane-dispersed amaMfengu—literally ‘the Wanderers’—to traverse the African continent. As they criss-cross the land, so the novel criss-crosses time: Ntabeni incorporates different eras into his work, including the anti-apartheid struggle and our contemporary moment, each clearly demarcated in the telling. Accordingly, The Wanderers brims with stories and themes familiar to South Africans and indeed the world: the Aids pandemic, ‘Struggle children’, abandonment, born-frees, transactional sex. We are greeted with the histories of the Sophiatown literati who fled South Africa in the 1970s and established their lives in other countries. Likewise, Ntabeni’s novel also explores the exile of uMkhonto weSizwe cadres in Botswana, Mozambique, Zimbabwe and elsewhere on the continent—and in the world.

In Tanzania, Phaks writes his ‘Pillow Books’, a series of vignettes in delicate but punching prose that echoes the writing of Todd Matshikiza, Arthur Nortje, Lewis Nkosi and Bloke Modisane. Consider the opening lines of Phaks’ short piece, Ravens and Prophecies_25/03/99:

The mist has hidden its face for a while. But I can still see its lingering whiskers on the river surface as the rising sun bakes the earth. Soon the sun will rise not for me. But, for now, I’m alive. Being alive is a constant act of finding value in atelic activities, a trick of staying ahead of the emptiness within. I think it was Camus who said the literal meaning of life is whatever you do that stops you from killing yourself. And I am saying the patience of the oyster is the only available way forward for a dying man, to coil within oneself, weaving one’s pearl.

Death is the end of desire.

This might have come straight from Themba’s pen as the Sophiatown giant wrote his story, collected posthumously in The Will to Die (1974), ‘Crepuscule’: ‘It is a crepuscular, shadow-life in which we wander as spectres seeking meaning for ourselves. And even the local, little legalities we invent are frowned upon.’

Or perhaps the stronger echo is found in the opening lines of Nortje’s ‘Waiting’:

The isolation of exile is a gutted

warehouse at the back of pleasure streets:

the waterfront of limbo stretches panoramically—

night the beautifier lets the lights

dance across the wharf.

I peer through the skull’s black windows

wondering what can credibly save me …

(July 1967)

Phaks’s narrative must surely take its place alongside theirs, even if his is a fictional account of the conundrum of the exiled freedom fighter, willing to give all to broker racial freedom and the end of apartheid, but stranded in banishment from the country, and almost irrelevant to it, as South Africa and its citizens move on regardless of who has left, or where they are, or why. To be stranded in this way is to handle the summary amputation of one’s personality, and it is Ntabeni’s deep negotiation of the ensuing self-reflection and reckoning that makes this novel so particular, and so important.

In Ruru, Ntabeni fulfils most ably contemporary demands for women protagonists who are compelling, complex, multifaceted, sexual beings. Ruru is independent, and yet predestined by her birth identity. Ntabeni delivers her story in her own voice, which he achieves most particularly by using ‘you’. In Ntabeni’s hands, this narrative conceit is innovated away from mere ‘second person narration’, and enables him to achieve the speaker’s tone so clearly that it reveals not ‘you’ but the character of the ‘I’ who speaks it:

As you lie in the darkness in the early morning, around two, the guardian angel hour, your naked thoughts demand to address your soul. You can hear the curtain breathing up and down from the wind like some kind of a lung. You think about how you have always craved a more capacious idea of a family but seemingly you’re always ending up with the capricious two. You have been charmed by Maman’s gentle personality, her indestructible optimism, and lack of hostility, her self-reserve, discipline, self-effacing kindness. You can now easily see how a man like Phaks would be besotted with her.

The Wanderers provides a deeply personal exploration of abandonment, as Ruru seeks out her father after her mother’s death, and he in turn seeks Ruru through his ‘winged words’. Ruru’s voice is allowed free rein in her letters to her mother, which makes for a defining portrait. The other women in the novel, ‘Mom’ Nosipho, Veli, ‘Maman’ Efuoa and Sandi, are as sensitively portrayed, and their perspectives as deeply fascinating. It is said that to hone his craft the Irish poet WB Yeats would choose random people and practise writing from their perspectives, so that the speakers in his poetry rang true even if far removed from his own voice. This is the writer’s craft. Ntabeni has talent for it in abundance.

One of the strongest features of Ntabeni’s novels is his own stylistic voice. Here is a storyteller in love with the art of telling tales. One gets carried away by his piercing observations and quiet contemplation, mingled with astute description and perceptive dialogue. His influences are eclectic: Virgil, Nietzsche, the Greek and Roman classics, Augustine, Biblical passages, theology, jazz, blues, music. French, Xhosa, Latin, slang. ‘WTF dude!’ precedes ‘mens sana in corpore sano’ by seven lines. Ntabeni insists on running the verbal gamut; there is no inkpot from which he will not draw, and he pulls it off. A certain propensity in South African fiction torwards insularity is disrupted at last by Ntabeni’s insistence that all may speak to African identities and issues:

I notice the prosaic desires I used to have, for food, wealth, sex and other corporeal needs sitting flaccid on the floor of my soul. They no longer stir my blood or quicken my soul. Could this be what Schopenhauer notoriously referred to as the futility of desire? When not having something is just as good as having it?

Saul of Tarsus, when he started calling himself Paul, says being alive or dead is all the same to him, as long as he obtains the power that was in Yeshua, his Christ. So the philosophers did not mislead after all. It does not happen that when you resign yourself to the demands of death you lose desires, that is the will to live in your body.

The Wanderers is a tragedy, using that sharpest of lenses to focus on the question of avoidable misfortune caused by human vice and folly. It is also Struggle literature, as noted, with Phaks as an anti-hero: a father who is no father, or a fighter, but only a foot soldier, one whom the ravages of war overtake, or a hero who devolves into a normal man. The work dabbles in the mode of the Bildungsroman as it charts young Ruru’s development from teenager to adult; and morphs into travel literature, starring the independent woman doctor Ruru with her freedoms and her adventures. It is a novel about death, pandemics, dying and the confrontation of mortality—grappling with the central questions of the point of life, of a life. The book insists on telling us about ordinary people, the ones whose actions accumulate to make history. Who can forget the grandfather who ‘tried to take another pull from his pipe, but it had gone out, so he settled for dragging and swallowing his own spittle’—?

Ntabeni combines his characters, modes and themes most masterfully, bringing us South African life and history in vivid hues. He weaves his stories into a rich narrative of life, the elements co-mingling and inflecting one another with meaning. All in the service of spinning a yarn, telling a tale. The result is a page-turner. Here is the voice of contemporary South African fiction.

- Joanne Ruth Davis is an African literary theorist. Her book on the English works of nineteenth century African intellectual Tiyo Soga Tiyo Soga: A Literary History won the Hiddingh-Currie Award 2019. She has published other academic papers on Soga, as well as African and African American women’s literature, archival research and the odd poem. She lives in London with her young family.