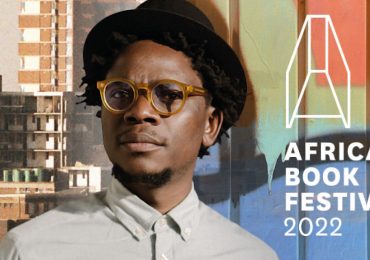

The JRB presents an excerpt from The Wanderers, a work in progress by Mphuthumi Ntabeni.

Ntabeni’s debut novel, The Broken River Tent, was recently awarded the Debut University of Johannesburg Prize for South African Writing in English.

~~~

The Colour of Time

I

The waiter, admiring the fawning smiles of the Bongo girls passing outside the restaurant, clipped the cup of tea on the edge of my table. Saa-maa-ha-nee! he apologised coyly as he dropped down to begin wiping the table. Noticing what happened, from his glass cubicle at the back, the manager slalomed through the thicket of restaurant chairs to assist. I’m sorry madam! Sorry I am. He’s new. You must forgive us!

He spoke in kindly embarrassment, helping with the wiping of the spilt tea with cupped hands before recalling he had a dish cloth tucked into his apron, which he took and used to wipe the table, gently elbowing the waiter out of the way. Ha-qu-na Ma-tah-tah. I tried to set him at ease, embarrassed by my halting Kiswahili. Hakuna Matata! No problem! Hakuna Matata. After a hurricane of apologies he calmed down. Whether he repeated the phrase to reassure me or mock my Disney World accent I wasn’t sure. Jina Langu Ni Asmail. He extended his hand to make sure there were no hard feelings while introducing himself.

O! Jina Langu Ni Ruru. Nice to meet you! Saa-maa-ha-nee. Said I, still in halting Kiswahili.

Karibu. Welcome to Bongo.

Asante! I said, gaining confidence from his non-judgemental acceptance of my linguistic inadequacy.

Are you liking your stay here? he asked after our perfunctory introductory remarks and my extended explanation of why I was in his country. We had entered into a maturing camaraderie. I managed to explain that I wasn’t a tourist but a medical doctor at the Mazimbu hospital in Morogoro, seventy kilometres from Dar. That I had come to Dar on a short visit to meet someone at the restaurant. I’m not sure how much he understood from my halting Kiswahili but we proceeded from reassuring clumsiness into triumphant familiarity very quickly.

The restaurant, precariously poised on the neck bend of Nyerere Road in Kariakoo city centre, had an air of Eastern exotic kitsch: Turkish carpets over cobblestone surfaces, drapes with tassels in the front window that concealed the heavyweight sound of the city traffic. Most of the buildings in the area displayed the cultural footprint of the German Bauhaus. They were now smeared in soot, dust and rust—the wear and tear of time. But they still carried themselves with an air of dignity that accentuated the pleasing confrontational balance between the minimalism and maximalist splendour of Bauhaus architectural poise, the cavalier rounding of corners to form a conversational meeting point between aesthetics and the ascetic.

Morogoro? My uncle lives with many goats there, said my friend, the manager, having come to inform me he would personally be serving me after the minor incident. I liked his manner of chatting me up to deflect the accretive awkwardness of sitting alone in a restaurant in a foreign city. It took my mind off the panic of being stood up by the person I was meeting. Again he left for the kitchen, where there were strange scouring sounds, after dropping the menu sheet. The milling crowds outside were chatting seriously, as people who are sure about the mysteries of faith always do. In Dar, Friday was the day of the week that had the muffled tone you find on Sundays in South Africa; their Sundays were as boisterous as our Saturdays. Their Saturdays, like this one, had a stranded quality about them. People congregated at the street stalls, dragging smoke from hookah vendors, trying hard to give themselves something to do while waiting for their decadent Sunday lunches.

Coming back after a few minutes, still with an air of domineering cordiality, the manager asked if I was ready to order. I think I will wait for my guest, I informed him. Meantime, can you tell me, pointing to the word Mishkaki on the menu, I asked, Nini Hii?

O! That is very tasty. Barbecued shish kebab served with peppers, chapati bread and fries. You should try it. I bet you’ll like it, said he, assuming a professional tone.

But isn’t it a little early for that? I asked with a smile. The freshly minted sun outside was still toddling.

Perhaps you like ugali with goat milk instead then? He threw his hands on his hips in mock disappointment, braiding it with a smile when I showed slight panicked confusion. From what he explained I understood ugali to be some kind of pap, a dryer equivalent of South African stiff-pap. I found the idea none too appetising either, for the morning.

Oh! It’s nguna? I enquired, trying to show off my street-wiseness.

Madam! We are a respectable establishment here. Nguna is street food, he said dismissively. We do it the traditional way, served with Moroccan lamb stew, or Kenyan sukuma wiki with collard greens if you don’t eat meat.

There was no rancour in his voice, but it amuses me that Europe, where restaurant culture has been the order of the day for centuries, is rediscovering its street food, while Africa, where street food is the order of the day, is now denigrating it as we become affluent, climbing onto the wagon of restaurant culture. Of course it has to do with class. Going into a restaurant is now one of the ways to flaunt your success.

I’ll wait for my guest and decide with him. Thanks! Perhaps you can give me a cup of coffee and a glass of water in the meantime? I replied, folding the menu.

Good, good! I have perfect one for you! Straight from Kenya! Full of aroma!

The restaurant had a homey cleanliness about it. Conversations between the patrons were boisterous. The pimple-like water drops of dew on the window panes were still oozing. I took out the magazine I had bought at the mall’s bookshop. My attention fell on an article about the colour of time. The writer, hemming and hawing to reach her point, was trying to convince us that the colour of time is blue—something I intuitively don’t dispute, despite her lack of empirical evidence beyond poetic musing. I like the idea of blue time, like the ocean or the sky. It gives you … hope, something tangible among the fleeting impressions. It is also logically not that bad: red signifies danger, something our senses intuitively agree with because we associate it with the spilling of blood; green and blue give us hope because they’re the primal colours of mother nature. So when going through time you do so with a mixture of red and green, danger and hope. And blue is the neutral territory in the sea and the sky—neutral, that is, when not stirred by the vengeful heart of Hera, the sister-wife of Zeus. There’s probably no way of imparting information about the colour of time without appearing foolishly didactic at some point, which is how the article ended, made worse by the author’s cloying need to express her cynical intellectual superiority.

I turned my eyes back to Dar, and the history I had researched before coming here. The House of Peace, دار السلام Dār as-Salām, Dar or Bongo if you are local, is the oldest city in Tanzania, founded on the charms of small coastal village called Mzizima, which in Kiswahili means ‘healthy town’. Dar, like most port cities, grew quickly into a ‘moral risk zone’, with the unsavoury influence of unlicensed liquor shops attracting prostitutes like flies on cow dung. According to recorders of the city’s early history—read priests, imams, starchy colonial government officials and district-police superintendents, themselves not too averse at spending stolen moments with the demimonde aspects of Bongo city—thought all this was not conducive to lawful order. The city’s nightly dance pleasures, and its population’s ‘lack of control of the impulses with regards to sexuality and aggression’, struck fear into official conservative hearts. But expanding festivities and venal appetites of greed, brought by the colonisers as they passed through the port on their way to Zanzibar for spices—the major foundational business of the city—proved too strong for conservative prissiness. So Bongo City survived and thrived. Her anatomy, to date, carries with it the scars of colonial influence in the form of dull but effective German architecture, late Bauhausian, and the cosmopolitan mix of Constantinople’s entrepreneurship.

Sitting at the restaurant, privy to how the workings of the sun distort the incommodious nature of seeing, I recalled all this to pass time. At the shoulder the road bends towards the harbour. There the surface undulates, and the pedestrians float on the melting contours of the horizon. It came to me as a metaphor for history, the tidying up of facts into memory. Philosophy has a similar problem of seeing, hence Plato’s cave parable. Things shimmer and undulate when observed from the outside. Giving them a narrative is our way of taming them, making them composite. I marvelled at the panoramic view, the glamorous beauty and the way the sun tinged the atmosphere with melancholy where it massaged the ageing buildings. Dusted in soot dandruff, and hugged by the biting autumnal winds, they gave off something of the vulnerability of old people walking with sticks in deserted places. Jack Kerouac, in his book of burning adventures On the Road, said everyone becomes mad with being alive when the sun hugs landscapes in its performance of autumnal dance.

II

Kplorm, a researcher at the South African consulate, is who I was waiting for. He had called about a week before, suggesting that we meet so he could share with me the latest information they had about my father in Tanzania. He had been useful in tracing the whereabouts of his grave in Morogoro. After speaking a few times over the phone we grew curious about each other. He seemed knowledgeable about many things, not least of which was where to go for good times and the rhythms of Bongo Flava. I learnt that though his name was Ghanaian, like his mother, his father was Xhosa. His parents had met at the University of Dar es Salaam. I decided to travel the two hundred kilometres from Morogoro, partly to meet up with him, but also to get rid of the stir craziness of a small village by checking out the Dar leisure scene. I wanted to move beyond the safe touristy parameters to the heart of the city’s local culture.

I imagined he would be about three or four years older than myself, thirty-five at most. I found myself often thinking about him, imagining how he looked, what he liked. He possessed a muted wit I read as psychological acuity. I craved conversational diversity beyond my work atmosphere. We had spoken about various topics, including contemporary African literature. He talked along the lines of ‘the glamourous mediocrity and fetish of sophisticated ignorance suppressing the authentic African voice’. I didn’t always follow what he meant but that phrase stuck in my head. I was becoming infatuated with him.

When I told my friend Sandy about him she flashed a red flag. Sounds like the dude is trying too hard to be woke, she demurred. Sandy, sharp as a blade, is the twenty-six year old daughter of a Tanzanian mother and South African Coloured dad, and the only person so far I can truly call a friend among my Tanzanian colleagues. We were sitting at the stoep entrance, behind the hospital. She said Kplorm sounded like the boring type who think they’re the real makoya, irrefutably Black. I bet he has a fixation on Fanon, disdains white males, but has an obsession for sleeping with white girls on top of a feigned superficial love for hip-hop music, she added, rolling her eyes. Admittedly some of what she was saying was hitting home.

We have a ferocious love for hip-hop and an obsession with Biko also, nobody accuses us of faking authentic blackness and wokeness? I clutched at a straw.

You know we the real bomb shister Ruru; we’s the diggs baby! You just catching them feelings girl, she said. Sandy and I often talk about the boring pressures of performative wokeness that is tickled by its own fickle fecklessness. She patted me on the shoulder and passed me the dagga zol.

~~~

- Mphuthumi Ntabeni is a political commentator and writer who lives in Cape Town. His debut novel, The Broken River Tent, was published by BlackBird Books in 2018.