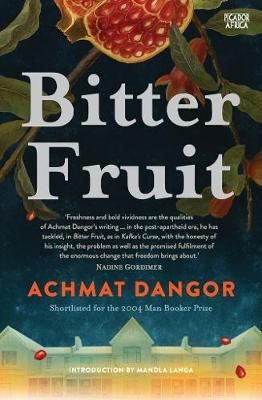

Achmat Dangor’s novel Bitter Fruit was first published twenty years ago by Kwela Books. It went on, after its United Kingdom release by Atlantic in 2004, to a shortlisting for the Booker Prize. Dangor, a founding Patron of The JRB, died last year. To mark the twentieth anniversary of his seminal work of South African literature, we present the following excerpt from Bitter Fruit, which has been rereleased by Picador Africa in recent years. The excerpt is prefaced by a publishing history of the book by his longtime agent, the poet Isobel Dixon.

Note: The JRB will host a literary commemoration of Achmat Dangor online on Tuesday, 2 November at 5.30pm SAST.

‘This is a city of fierce thunderstorms, quick and transient’

—Bitter Fruit

Achmat Dangor’s writing came to me in the early days of my publishing life as a rich, mysterious gift. I was fortunate to be asked by Achmat’s South African publisher, Annari van der Merwe, to sell international rights to Kafka’s Curse, which she had published at Kwela Books. It was bought by a discerning young editor, Dawn Davis, at Pantheon in the United States, hailed as a New York Times Notable Book on publication in 1999, and translated into six languages. The Baltimore Sun wrote: ‘It is entirely wonderful: delicious, moving, mysterious, wise, and profoundly provocative. Read it.’ As I read that now, I think of how in so many ways Achmat himself was ‘mysterious, wise, and profoundly provocative’. An old soul, with a great capacity for mischief, as well as a deep empathy and kindness. Like his writing—multifaceted, hard to pin down.

It was the days before PDFs, I read and posted paper manuscripts and books to publishers, and Annari and I emailed messages and faxed reviews and tax forms and contracts back and forth. What was Achmat writing next? I asked, what can publishers follow this with? A ‘bigger’ book, about the ‘New South Africa’—a draft Achmat completed while on a hectic work and travel schedule as head of the Nelson Mandela Children’s Fund. One day in Joburg, Amsterdam the next, then meeting the King and Queen of Spain, I would hear from Annari, as we both tried to pin him down and engineer meetings with his international publishers. But somehow ‘though not master of his own time’ as Annari wrote to me, Achmat made the time and wrote the tremendous manuscript that became Bitter Fruit. Though I learned this later, Ivan Vladislavić edited the manuscript for Kwela. I read the text in awe and emailed to say what a lacerating and powerful novel it was. This time, I was sure, a UK publisher would see the light too.

To cut a very long publishing story short, it took some time. Bitter Fruit was bought in France, Spain and Canada first, and turned down by more than twenty English editors before Toby Mundy of Atlantic and I had a long conversation over lunch and he decided to take a second look, having passed earlier. The novel—as it does—had continued to haunt him. Atlantic was publishing Damon Galgut’s The Good Doctor as well and, as it turned out, Damon was shortlisted for the Booker in 2003, and Achmat’s Bitter Fruit followed suit in 2004, after publication to many fine reviews. Morgan Entrekin and Amy Hundley came on board for Grove Atlantic in the US and other translation deals followed. (Though Achmat didn’t win the big prize, it was an extraordinary night, though my favourite parts were away from the big hall and the television cameras, in a quieter space, with Achmat and his wife Audrey dancing at our late Booker afterparty in Soho.)

Writing this, I reread Amy’s acquisition press release quote: ‘Achmat Dangor’s portrayal of multicultural South Africa is incredibly fresh, and this new novel is accomplished and beautiful, with a tense and complex awareness of the way history continues to refract into our contemporary lives.’ That tense and complex awareness—and again I think of Achmat himself through the word of a review. That close observation, the sharp sideways eye, a discerning look, as if he could see straight through you, though wryly, not unkindly.

A favourite photo showing that wryly amused and measured sideways gaze is one I took of Achmat across a Camden restaurant table, perhaps on the Booker shortlisting trip. It accompanies this article. You could never tell what he would say next, he did not traffic in cliché or platitude or the superficial. In conversation he would come at a thing softly, softly, but clearly, from a surprising angle. But a different, deeper fierceness, anger at injustice, blazed right through his work, both on paper and in the world. A complex and tender fierceness that that keeps speaking to readers of Bitter Fruit – since republished in South Africa by Terry Morris and Andrea Nattrass for Picador Africa – and his further work. We only wish there was more.

‘Freshness and boldness and vividness are qualities of his writing,’ Nadine Gordimer wrote. ‘He has always delved beyond the surface of human relations, from the intimately personal to the societal and political.’ And these words, which struck me afresh, from Hazel Rochman in Booklist: ‘Dangor writes from the inside and yet with distance, challenging some sacred platitudes of the heroic struggle and the new elite but never settling for the easy ambiguity that dismisses all values as being the same. Told from many characters’ viewpoints—anguished, angry, tender, ironic—the searing narratives reveal the wounds of betrayal and no reconciliation. The people and their stories are unforgettable’.

Unforgettable stories, and an unforgettable storyteller. To do him honour, we remember, and we read.

*

Bitter Fruit

Achmat Dangor

Kwela, 2001

Atlantic, 2004

Harper Perennial, 2006

Picador Africa, 2017

From Chapter 3:

Dawn. Mikey lies in bed and observes the sun, still pale, feeble almost, on the dark rows of books that line the shelves in his room. ‘And you are still so young!’ Vinu had said, when she saw his books. He remembers the way she rolled her eyes, mocking, declaring herself ‘forever chaste’, saved from ‘concubinage’ because the Lord Vishnu was too busy with his books to ‘truly’ see her beauty. She had come, seeking not sex, but refuge from the carnage of her parents’ broken marriage. Her language was a means of escape, its suggestiveness entirely rhetorical. But she did say that she smelled history in this house, too much history, and then promptly fell asleep.

Mikey thinks back to the debate they had in class a few days ago. ‘Homer’s Odyssey is the basis of the modern novel,’ Miss Anderson had said, looking expectantly at her students. ‘Well, I think so,’ she’d added, when she saw the indifferent expressions on their faces. Lecturing in English literature is a sad profession, it seems, a refuge for failed writers. Miss Anderson once tried her hand at it, gave up, bored with the book she had ‘lived with’ for ten years. She has started writing again, in secret now, it is said, no longer discusses her ‘work in progress’ with friends. Now she confronts her class with the undeveloped ghosts of last night’s writing. Wasted on these spoiled, post-apartheid hedonists. She resorts to the desperate intensity of a writer still struggling with her words. Rumours of a tragic love affair with someone who is now in a powerful position. He—a Cabinet minister, it is said—divested himself of Miss Anderson, the ‘white bit on the side’, exponentially decreasing his involvement with her as he rose in the ranks. The inspiration of her creative rebirth is that she was ‘got rid of ’, love abandoned for power.

Does some of her research among male students, and takes comfort there. Mikey can’t see why they find her attractive. Thin, gaunt-faced, her shoulder-length hair flecked with grey. Perhaps some new vein of excitement has been opened, the promise of unleashed passion, it glows in her, the tender skin of love gone wrong.

He does not particularly dislike Julia Anderson, Mikey decides; well, perhaps only when she assumes the mantle of literary prophet and starts speaking in well-turned phrases. It makes her seem uglier than she really is, her emaciated features gathered into a fierce scowl. Who can kiss such thin lips? And she always picks on him, uses him as the sounding board for the answers she hopes to get from others. His diffidence, his obvious boredom, provokes her.

‘Well, Mr Ali, what do you think of Homer’s Odyssey?’

‘It is clichéd,’ Mikey answers.

Give her the poker-faced treatment, sometimes forces her to direct her venom elsewhere.

‘Really?’

‘Really.’

‘Example?’

‘“The pink fingers of dawn.” Imagine the sun rising like that?’

‘A metaphor for its time.’

‘Clichéd,’ he insists.

‘No, worse,’ Karabo Nkosi says. ‘Eurocentric.’

‘For God’s sake! It’s set in Europe. It’s about Europe!’

‘But the Greeks are darkies like us,’ Vinu says.

‘Clichéd, that’s all,’ Mikey says.

‘Think about it, Miss Anderson: the pink fingers of dawn over Sandton!’ Karabo says.

‘Is that where you live?’ Miss Anderson asks, looking at Mikey.

‘Who, me? No, I live in Berea.’

‘The township in the suburbs, Miss Anderson, that’s where Mikey lives.’

‘Still, Homer Eurocentric and clichéd?’

‘Dawn would have to be a white woman, then, with pink fingers, is that not Eurocentric?’ Karabo asks triumphantly. He has Miss Anderson’s measure, he thinks.

‘Do you have pink fingers, Miss Anderson, can we see your fingers?’ Vinu asks, her fervour false. Surely Miss Anderson must see the mockery of it all.

Vinu won the debate, no doubt about that. We bring down the false gods/ All the gods/ Until there are none … Mocking verse from the struggle era. Anonymous. Mikey turns onto his stomach, listens to his father in the bathroom, cleaning his teeth, blowing his nose. Will I harrumph-harrumph like that when I get to be his age?

He thinks now about his mother, her legs up in traction, the loveliness of a trapped animal. He has never thought of his mother as lovely before. Well, nothing wrong with that. Growing up means being able to recognise things such as the loveliness of people. Her family calls him ‘ougat’ because he recognises the loveliness of people. But his mother’s distance bothers him, the feeling that she is detached from her surroundings, that she is burrowing into her pain for comfort. Even he feels that this observation is facetious, that grown-up tendency to bury uncomfortable thoughts in ‘constructions’. The Julia Anderson syndrome.

But he does not know his mother any more, he thinks. ‘I do not know my mother,’ he says out loud.

There is a sudden silence in the bathroom. Is his father listening, Odysseus eavesdropping, suspicious of Telemachus’s loud musing about Penelope? Intellectual shit. Father is downstairs staring soulfully into his bowl of cereal. How senile does a man become when he is close to fifty, how sentimental, how fuzzy-headed and weak-hearted?

And my mother, what does she think about, does she think at all?

Of course she does. He has seen her sitting at her ‘bureau’, as she calls it, in the alcove between her bedroom and the door to the balcony, a haven created by an architectural miscalculation, writing in that diary of hers. Bent over, absorbed, an intensity that lasts for hours. What? A novel? A historical record of the lives they have lived? She and her husband, minor actors in the blockbuster movie Liberation! Bewildered rats, trembling with excitement, the pink-fingered dawn of history before them.

No, not a novel, hers is not the posture of a fictionaliser, never any amusement in her face, no smile of pleasure at an unexpected turn of phrase, no, something much drier, the details of their struggle, tales of petty heroism. Or is it something deeper, a delving into herself?

The silence in the bathroom endures, a quality of absence. His father is downstairs, fidgeting with the clock in the kitchen, always losing time, a genetic fault. Timepieces are like human beings, they have built-in flaws. Silas is waiting to hear if Mikey is up. There is no need for him to rise so early, varsity in recess, Miss Anderson on a beach somewhere, masturbating to the rhythm of Homeric hexameters.

The front door slams, the car starts, pulls out of the driveway with a loud, wet squelch. So it is raining out there. Silas wants Mikey to know that time is moving on, his oblique way of remonstrating with his son for his indolence. My father the stoic, can’t tell you a thing when you look him in the eyes. And yet, there he is, dealing with the country’s problems, trying to reconcile the irreconcilable.

Mikey rises, places Oupapa Ali’s glowing fragment of Kaaba stone, which he uses to illuminate the desolation of urban nights, back in its soft receptacle of clean underpants, and pads to the bathroom. He urinates, watches the steamed froth with some satisfaction, shivers with delight at the end. How pleasing the simplest of our acts of gratification. But it is too cold to go about the house naked. Nature always getting in the way. He returns to his room, slips on a T-shirt and jeans over his chilled body, imagines the smell of coffee in the kitchen. The only indulgence he has detected in his father.

The sun breaks through the strangely sullen sky—this is a city of fierce thunderstorms, quick and transient, not used to this lingering greyness—and fills Lydia’s alcove with a sudden brightness. Mikey pauses at her desk. A few unopened bills (does she owe people money independently of Silas?), a letter with a Canadian postmark. Probably Aunt Martha. Wonder how Mireille is? He tries the drawers, conscious of his own guileful posture, the sideways manner in which he pulls at each handle in turn. They are locked. His sense of intrigue grows.

Mikey rummages about in the old tool cabinet—an array of once immaculately clean screwdrivers, hammers, wrenches, grown rusty and blunt with disuse, testimony to Silas’s changed station in life—and finds the bunch of keys. Once it must have been a simple collection of duplicates, but over the years, Silas has added stray keys picked up in the street, or abandoned by friends and colleagues when they moved homes and offices. Mikey remembers seeing Silas take the key from a cupboard in a second-hand furniture shop and slip it into his pocket, his face lit up with a shoplifter’s secret enjoyment. Now the bunch resembles the jangling credentials of an ancient turnkey, the guardian of some vast, medieval dungeon. A marvellously practical habit, revealing of yet another obsessive side to Silas’s bland character?

Mikey quickly finds a key that fits Lydia’s desk drawers. Indeed, she had locked them as an expression of her privacy, rather than in any real hope of keeping out an intruder. He sifts idly through the memorabilia of a rather ordinary life. Entrance tickets to the Johannesburg Zoo (marked ‘Non-White Day’), an invitation to Gracie and Alec’s wedding, cancelled cheques, abandoned invoices for goods purchased. A solitary dried carnation, preserved, together with a florist’s card simply inscribed ‘Love’, in one of those zipped polythene kitchen bags, provided a romantic touch. But whose love, whose errant love is being commemorated? Certainly not Silas’s. His businesslike approach demands grand gestures, huge and overflowing bouquets, their imposing beauty transient and superficial. What he is like in the throes of passion, Mikey wonders. Then dismisses the image of bulging eyes and limbs clumsily entwined. He knows that Silas has spindly legs and that Lydia has hair under her arms, the sprouting of which she struggles to control.

Lydia’s diary lies hidden, the only real attempt to conceal anything, underneath a sheaf of ancient legal documents: insurance policies, birth certificates, expired vehicle registration papers, the deed of sale to a house disposed of years ago, matters that are usually the preserve of husbands. Now Mikey begins to comprehend the extent to which Lydia, by default, manages the family’s affairs. Anyway, collecting obsolete documents, in neat piles but without any obvious order or purpose, is the obsessive habit of people besieged by the constant fear of poverty. Do the rich preserve their past as assiduously?

With Lydia’s diary on his simple breakfast tray, alongside the heated-up remnants of the coffee that Silas had made, and cereal soaked in orange juice (he cannot abide the taste of milk so early in the day), Mikey sits now in the rain-drenched garden at the back of the house. It is no more than a quadrangle of grass bordered by dying flower beds—don’t plant exotics, not just before winter, he had heard Lydia tell Silas in a rare moment of domestic engagement (even if it was only to disagree). Mikey expects to glance, very leisurely, through the minor traumas of a life lived as best she could. Given Lydia’s beginnings, parents like Mam Agnes and Jackson, a husband like Silas, what could his mother have recorded in her diary but the routine passage of life, births, deaths, petty cruelties and vain hopes? Nothing momentous in here, he tells himself, trying to dismiss the feeling of guilt that comes more at the remembrance of how easy it was to invade her privacy, than at the prospect of trespassing onto the secret domain of her life.

Yet, when he cannot bring himself to read the first entry, it is not a sense of decency that deters him, for ‘every enquiring mind has the right to know even the forbidden’, he rationalises, but an unexpected foreboding. This diary has something to do with Lydia’s accident, her subsequent hospitalisation, with the name Du Boise that he has heard his parents whisper tensely between them in the hospital room.

A ghost from the past, a mythical phantom embedded in the ‘historical memory’ of those who were active in the struggle. Historical memory. It is a term that seems illogical and contradictory to Mikey; after all, history is memory. Yet, it has an air of inevitability, solemn and compelling, especially when uttered by Silas and his comrades. It explains everything, the violence periodically sweeping the country, the crime rate, even the strange ‘upsurge’ of brutality against women. It is as if history has a remembering process of its own, one that gives life to its imaginary monsters. Now his mother and father have received a visitation from that dark past, some terrible memory brought to life.

This excerpt from Bitter Fruit was selected by Achmat’s co-founding patron of The JRB, Ivan Vladislavić, who was also the novel’s editor.