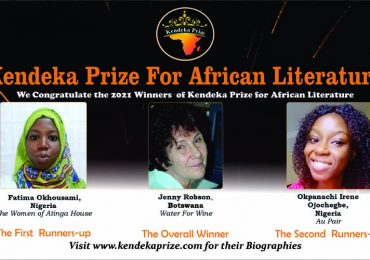

The winners of the inaugural Kendeka Prize for African Literature have been announced in Thika, Kenya.

From a shortlist of five short stories, Jenny Robson of Botswana won the Kshs 100,000 (about R13,500) first prize for her story, ‘Water For Wine’, while Fatima Okhousami and Okpanachi Irene Ojochegbe, both of Nigeria, won Kshs 50,000 and Kshs 25,000 for their stories, ‘The Women of Atinga House’ and ‘Au Pair’, respectively.

Chair of judges Lucas Wafula (Kenya), was joined by authors and literary activists Edwige Renée Dro (Côte d’Ivoire) and Rémy Ngamije (Namibia-Rwanda) in selecting the winners.

The prize is sponsored by Solano Publications Ltd, and is overseen by a Board of Advisors chaired by James Murua (Kenya).

The Johannesburg Review of Books will publish the winning stories in our October edition.

Chair of the judges Lucas Wafula sent through the following thoughts on this year’s prize, and its winner:

Being a judge in an augural literary prize is unsettling in itself; chairing the judging panel compounds the anxiety because inaugural in most cases nearly equals to groping in the dark. This is the reason I am excited that we have successfully concluded our assignment as judges of the inaugural Kendeka Prize for African Literature—2021. I couldn’t be more grateful to, and proud of, my colleague judges, Edwige-Renée Dro, from Ivory Coast and Rémy Ngamije, from Namibia. They made the whole process interesting, easy and the debates intellectually stimulating. Without Andrew Maina and the Kendeka board of directors, there would be no prize to talk about. We are most grateful to them. Finally, the writers, who hit their keyboards and saw us receiving stories from across the continent—thank you.

As judges were simply looking for a good story. A story that grabs you and says, read me. A story that draws you in and takes you on a journey. A story that reflects Africa, our lives as human beings, and the challenges that we all grapple with. And there were a number of such stories that contained these ingredients and many that did not reach the threshold.

Some of the stories that had the most interesting and ambitious plots sadly, fizzled out towards the end. One would feel that the writer had suddenly realised that they had gone beyond the word limit and as such must end the story. A story, in my view, and my colleague judges would agree, should conclude and not end. It should leave the reader feeling that there is more happening beyond the now—even though we may not see it.

There were stories that had some philosophical rumination that we could not understand—whether these elements were insertions or observations by the narrator. There were others that had misdirection in sequencing or had good premise that was not carried all the way through, with writers fumbling with what would be considered as basic elements of what a good story should be.

Conversely, there were stories that stood out; stories that brought smiles on our faces and will excite readers. One of the stories that hit the right chords with all the judges was ‘Water for Wine’. To us, this was the best of example, stylistically, of literature.

The author of this story deals with very complex issues within a short word count with a clear focus of what a story is and what it isn’t. This is a story that comes from a larger universe. The reader gets a feeling that after the story concludes, the protagonist still faces challenges as a nurse-aid and as a person with conflict in faith. Kelabogile is still trapped in a universe that she cannot successfully escape. The language applied to this story is simple, clear and effective. Its ingredients are delicious enough in themselves to not warrant extra spices. It is an adventurous and rewarding story to showcase to the world.

In terms of simplicity and style, ‘Water for Wine’ does what one might consider the simplest of things, which is actually, the hardest to achieve: being true to a narrative; the writer immersing themselves in one character, knowing their challenges and strives and also the place – the setting of the story, and being aware of the challenges in this place while dealing with complex cultural discussions around death, spirituality, religion, class differences—between the doctors, nurses, the nurse-aid and the peasants, poverty—gender roles—this nurse-aid wonders why male nurses are also referred to as sisters, family relations, and so on.

‘Water for Wine’ embodies the aspects of a challenging short story, which you read and imagine the protagonist in other circumstances beyond now. It is a story that shocks the reader into seeing what is happening around them, causing them to see the main character right there with them. This is a story that does not have assumptions about the reader’s capability; it allows them to think and draw their own conclusions.

The writer did very well to not only tell a complex story in a simple way but also, accord the main character, a nurse-aid, (who represents the lowly in society) a personal sense of dignity and she respected and presented the main character’s amazing cultural intelligence very well.I must urge writers, especially those who wish to tackle a commonplace or cliché topic, to remember to approach such a topic in a different, engaging and interesting way. We must remember that every chef looks at an onion and sees an onion. Therefore, it is what you do with the onion that matters.

Writers must be careful not to take on too much, when it comes to short story writing. If you do, you will surprised at how quickly you will be humbled by the word count. You can only do so much in a limited space: This is not to say that a short story is short or cut, no. It is a whole story, with all the requisite ingredients, told within a limited word count.

Thank you.