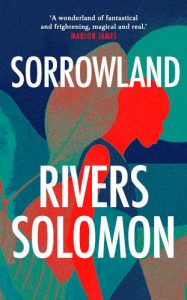

Rivers Solomon’s Sorrowland rearranges the furniture of the hardening genre of novels resolved to deal with North America’s history of racial violence, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

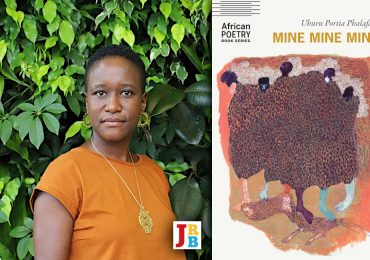

Sorrowland

Rivers Solomon

#Merky Books, 2021

The great enemy of the contemporary novel is TV. As the beat of cultural life is increasingly filtered through the watch-it-now lens of on-demand television shows, so many new novels have taken on a pacing and rhythm that presages their adaptation for Netflix. Partly, this is because the long-worn sense that writers ought to respond to the world in which they find themselves is the driving impulse of much that is great in contemporary literature. If our current climate of anxiety produces much dramatic potential for the novelist, it is also susceptible to producing a kind of novel that often feels too comfortably attuned to the idea of ‘reckoning with the past’ as a cathartic rehearsal of past wrongs, and is thus diminished as a result.

Sorrowland, the blazing third novel by Rivers Solomon (who uses fae/faer pronouns), is an interesting example in this regard. The spec-fic text arrives from the Stormzy-linked Penguin imprint #Merky Books as a sweeping page-turner of a story that aerates the author’s favoured forms—memory, trauma, the speculative—as part of a boldly inventive construction that runs to 355 richly dramatic pages. The central character is Vern, an intelligent and thoughtful fifteen-year-old who escapes from an African American separatist cult known as the Blessed Acres of Cain, whose leader has shackled her to himself in a dubious marriage. Vern is heavily pregnant when we encounter her, and she flees from ‘Cainland’ (shades of the plantation, overlays of Herman Cain) into a wooded forest where she gives birth, pursued all the while by a sinister catcher who Vern calls ‘the fiend’:

A gutted deer with its dead fawn fetus curled beside; a skinned raccoon staked to a trunk, body clothed in an infant’s sleepsuit; and everywhere, everywhere, cottontails hung from trees, necks in nooses and feet clad in baby bootees. The fiend’s kills, always maternal in message, revealed a commitment to theme rarely seen outside of a five-year-old’s birthday party.

The hostile memento mori are meant to remind Vern that her two children, the divergently characterful twins Howling and Feral, are not safe as long as she remains in the woods. Vern, whose athletic resourcefulness belies her desperately poor eyesight (of which more later), is unfazed and determined to survive. She lives in the woods for four hard years, surviving on instinct and the closely held determination to find her first love, Lucy.

But the woods are filled with many hallucinatory horrors, and Vern becomes increasingly unable to separate herself from the ‘hauntings’, ghostly apparitions which begin to proliferate the longer she spends in the forest. Vern finds herself in the grip of something strange and ambivalent, a fungal stirring within her that gives her the ability to heal herself when she is injured and provides her with superhuman strength. Unfortunately, these gifts are accompanied by crippling pain that culminates in her sprouting an exoskeletal growth on her back, which spreads rapidly.

So far, so sci-fi. The story that follows is a filmic epic that manages to be enjoyably readable, replete as it is with Sixth Sense-style ghosts, intensely brutal fight sequences, a stutteringly intimate romance (although introducing a Native American love interest and having her function merely as plot advancement is a strange faux pas), and an unfolding narrative that begins to signal to the possibility of a follow-up a little too early. Solomon is an admirably confident storyteller, and faer control over story brings to mind Parable of the Sower-era Octavia Butler. The narrative levitates in the unmanageable tension between the certainty of seclusion and the uncertainty of what lies waiting in the future. It becomes a journeying epic without overwhelming the reader in a frantic crescendo of plot.

Certainly, in Vern—a queer, non-binary, near-invincible mother with albinism—Solomon has a compellingly affecting hero figure for the remaking of the human. Confined to the isolationist commune for as long as she could remember, Vern’s forays outside suggest a daunting world of seductions and dangers. We never forget that of the many things that mark her as different, Vern’s Blackness is the one that draws the threat of visibility closer. At one point, having stolen some suburban-mom clothing from a shop, Vern allows herself to imagine an alternate world in which she is—

a white suburban mam in tennis shoes and leggings […] Later she’d go running, put her kids Callum and Bruno into the jogger. Find a park. Find a woods. Get lost in it. Never return. Till her husband called. Susannah. Where are you? Some things were the same in Cainland and out, and husbands calling to demand your presence was one of them.

What part of Vern desires the normalcy of whiteness, its bland oblivious everyday certainties? See how the fantasy drifts, either pulled by one reality (the safety of the woods) or gratingly grounded by the presence of a man? But the dream is jerked roughly back to the scene of contemporary American violence through a police stop that we see through the uncomprehendingly curious gaze of the children:

They wore blue clothing, crisp and tight. ‘Do you have some kind of ID?’ One of them asked Mam.

‘Not on me, no, I’m afraid,’ Mam said, her face stern but calm. Her voice was wrong, stiff and strange and high, a copy of the person talking to her. Howling tucked himself behind her thighs, just as Feral did.‘And your name?

‘Susannah,’ she said.

‘And your children?’

‘Callum and Bruno,’ said Mam, and Howling knew he wasn’t supposed to tell these blue-suited people that was a lie. These strangers, they were like bears. Stand still, stay quiet, back away ever so slowly, slower than a snail creeping along your arm, and most important, don’t interrupt Mam in the middle of her negotiations. Mam thought Howling never listened, but he did. One of the blues knelt in front of Howling.

‘Are you all right, son?’ he asked.

Howling looked up at Mam and she smiled down at him. A fake smile. A tense smile. Yes, these blues were bears.

In the blur of action, it is sometimes easy to forget that Vern is effectively a child herself. The novel’s rather unbalanced timeline, with great leaps forward and backward acting as plot legerdemain, brings us back to the idea that what we’re reading is a stumbling kind of coming-of-age story. Blessedly, the novel spares us any save-the-children sentimentality (for large sections of time, the children are off-stage, so we may ask why they are there), but it is sometimes unclear if the character’s tentativeness in defining herself is purely her own, or an effect of the author’s lack of clarity.

Perhaps the novel is attempting too much. A novel that layers so much together so tightly—queer love, self-acceptance, generational trauma and other touchpoints all feature—risks bulging in an unseemly way. That the novel almost manages it says much for Solomon’s talent: the narrative rarely sags, so forceful is its energy. And of course, by centring a queer protagonist, Solomon reminds us that many of the earliest Black abolitionists were women, and that queer Black activists from Audre Lorde through to Bayard Rustin have been critical voices in the struggle for freedom in North America.

In this regard, Sorrowland rearranges the furniture of a hardening genre, the cluster of recent novels that are of one accord in their resolve to deal with North America’s long and blood-soaked history of racial violence. This deeply committed genre of novels that bring the scene of injustice—its repression and its tangled memory—to the arena of fiction is populated by a cast of uneven talent. Some of them, like Ta-Nehisi Coates’s The Water Dancer, are deeply sentimental for a Baldwin-esque reckoning with the curve of Black history in America. Others, like Jesmyn Ward’s Sing Unburied Sing, stir the dark depths of the Southern Gothic to find what lies beneath. Whether these novels will endure beyond their moment in the reading spotlight remains to be seen, but there is a nagging sense that—committed as they are to their collective project of recovery—they feel embedded in something that ignores the rest of the world.

The point is made quite clearly in Sorrowland when one of the characters helpfully reels off a bit of Langston Hughes: ‘The poem was called “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”, and Vern wondered if it was possible that the fungus was Black. Born in Africa. A watchful spirit looking after her people.’ This sort of folksy commonplace, where Africa is consigned to the loosely defined consoling beforelife of Black life in North America, counts as a reductive imagining of Blackness.

For all of that, Sorrowland has rather more about it that is compelling. If Solomon’s writing occasionally jars with the way it darts indecisively between the inner worlds of the various protagonists (and giving over narrative to toddlers can prove taxing on the reader), and if fae makes the young writer’s mistake of trying to fit too much into the book (judicious trimming would have removed the clanging ghost-orgy that Vern facilitates in a motel-room), then fea nevertheless manages to achieve a novel that is entertaining and provocative. Cainland, for instance, is a masterful creation that satirises a certain mode of Hotepry with a nuanced hand. The inhabitants are strapped down in their beds every evening in deference to their night terrors (the same hauntings that Vern sees), and their leader, the predatory Reverend Sherman, is a Farrakhan-esque charlatan whose demise is one of the novel’s unsatisfying plot points, happening as it does off stage.

Ultimately, the undoing of Sorrowland is that it rushes on where we wish it would linger, and it dallies too long in uninteresting scenery. Some adjustment here and there could have produced a sharper novel. As it is, it lapses too often into telling rather than showing, abounding with moments of such piercing truthiness that it’s a shame the words can’t always keep up.

- Editorial Advisory Panel member Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.