For the next three days, The JRB will be publishing the three winning stories from this year’s Short Story Day Africa Prize.

The winners of the 2020/21 Short Story Day Africa Prize were announced on Monday. This year’s winner is Idza Luhumyo from Kenya, for her story ‘Five Years Next Sunday’. Zambian writer Mbozi Haimbe earned 1st Runner up for her story ‘Shelter’, and Alithanayn Abdulkareem of Nigeria was 2nd Runner with ‘Static’.

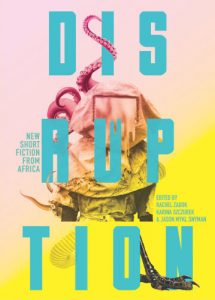

The winners will receive prize money of $800 (about R11,400), $200 and $100, respectively, and their stories, along with the rest of the longlist, will be published in Disruption: New Short Fiction from Africa, due out from Catalyst Press in September 2021.

Today, we’re sharing the full text of ‘Static’. Keep an eye on The JRB tomorrow and Friday for the remaining two stories, or sign up here to receive all three stories in your email inbox on Friday.

~~~

Static

Alithnayn Abdulkareem

2nd Runner-up of the 2019/20 Short Story Day Africa Prize

The headline reads A Series of Record Droughts Plague Eko. I run the newspaper over my sweaty neck and cleavage as I climb the stairs. Experts can be really obtuse sometimes. Anybody here could have told them droughts were inevitable; it hasn’t rained in Eko for years. All the clouds resemble upside down volcanoes. I’ve stopped looking up, the sky has a dusty orange filter these days. I’m waiting for lava to flow from the heavens and burn us all up.

I reach the fifth floor and turn the door knob. My clammy palm slips against the smooth metal and I fall, jarring my knees. I twist it again and the door opens. The air inside the apartment reaches out to me. I gag and cough, and stagger back. I remove my T-shirt and tie it across my face before entering. The smell heats its way through the fabric covering my nose till my eyes weep. I can even taste it through the cotton. It makes me think of the first time Maami made me clean a pot of rotten rice and maggots. I put my hand inside it, and threw up in the sink. She still made me clean the pot. I didn’t know it then, but it was a good precursor for my body, training me to deal better with rotten things.

I open the window and the silence is sliced when one fly enters, then another. They land on Maami’s dead body by the fridge. I look around the apartment: cream walls, the fridge in a corner, one window to outside. No pictures on the wall. Printers require ink and ink requires water, so photographs are now a luxury. I step over Maami’s body to the table where a jug of water gathers a film of dust. I remove the T-shirt and hold my breath while swallowing. The water touches my stomach and makes a U-turn, carrying everything already inside me back up in the wave. I run to the bathroom and lean over the toilet. Plantain chips and water gush into the bowl. The mess swirls down the drain too quickly for me to comprehend what has just left me.

I’ve only ever seen one dead body before Maami’s, and I couldn’t smell him. At his funeral, Maami’s hand pushed my head into her chest. I don’t think she meant to press that hard, but she was using her other hand to shake the hands of the mourners who’d come to pay their respects and it would have been impolite to grip them tight. So she placed all her tension on me. She smelled like a song, I don’t know how else to describe it, but she held me and I started hearing all those songs in Hausa movies, the ones with too much autotune and saccharine metaphors for love, ‘kamar soyaya’.

I squat over Maami’s body. Her dress has ridden up and I can see the under-curve of her left breast. One hand is stretched out, the other is on her chest. I lower her lids, the only things I’ve touched in the thirty-six hours since she stopped breathing.

I wash my hands with vodka and water, then yank the sheets off my bed and place them over her before moving my mattress to the window, as far from her as possible. I flop onto the bare foam. It’s my first time rooming with a dead person. There is no weight anywhere, nothing shudders, nothing stiffens the hairs on my neck. In the dark, covered with my bedsheet, Maami could pass for furniture, any mundane object hidden till its usefulness required the covering to be removed. I imagine that she is alive and snoring. Over the years, that dragging of mucus from her nostrils to throat functioned as a lullaby. I close my eyes till Khail knocks on my door.

I let him in and he surveys the mess. ‘Let’s do this,’ he sighs.

He takes her arms and I take her legs, pumping the muscles in our calves to raise her off the ground. A dead body doesn’t move like a live one, it sags in ungainly ways, and we constantly have to readjust to keep her from reuniting with gravity. The stairway is not wide enough to make turning easy. To manoeuvre, Khail and I bend and stretch her as needed, folding her into a V to turn, then back into an I as we descend each new flight of stairs.

My phone vibrates in my pocket, an inconvenience I ignore. We reach the ground floor and let her go. Her body makes a plush sucking sound on the concrete.

‘I’m tired and thirsty,’ I tell Khail.

‘Yeah.’ He takes Maami’s arms and drags her along the ground. My phone vibrates again. I pick up. The number seems familiar, but there is no caller ID.

‘Hello.’

‘Good day from Planet One. Please state your name and identity number after the tone.’

I suppress a shudder. No matter how good Planet One’s AI gets at mimicry, the speed and timbre of its voice always gives it away.

‘Amina Saud, A00012727,’ I say.

‘What is your father’s name?’ the AI asks the secret question I gave them during the compatibility tests. The question catches me off guard. I hesitate. It repeats the question.

‘He has no name, he’s dead.’

‘Congratulations, Miss Amina Saud. You have been selected by the interplanetary lottery board as a finalist. Due to your excellent physical and mental assessment scores, we are pleased to make you an offer to join the new crop of migrants to Planet Forma. Press one if you accept, press two if you decline.’

I hold the phone away and look at Khail dragging Maami away. Bits of skin and black blood rub off on the gravel, sticking to the ground like clues leading to her grave. I stop and put the phone back to my ear.

The message repeats on a loop. My fingers hover between one and two. Why is there no option for further questions?

I press one.

The AI thanks me and spews some information I don’t bother to retain as it will be sent to me. I almost miss the instructions to press hash if I have any queries. I press hash.

‘Why me?’

It replies in an electro-word jumble as if, somewhere, a desk robot is typing a response being read out by a phone robot.

‘You were an excellent fit with our criteria. Physically and otherwise.’ Finally, something coherent. It might be poor at tone, but Planet One’s AI is excellent at subtext. I’m fertile, I’m poor enough to be desperate, and I carry genes from two different races.

‘Well thank you. What is the next step?’

‘A package will arrive tomorrow or the next day with further instructions. Congratulations once more. Have a great day.’

‘You too, thanks.’ I say, but the call is already finished.

I walk faster, hope filling my ankles with new energy. When I catch up with Khail, there is already a fresh hole.

‘How?’

‘Yesterday. Friends at midnight.’

‘Allah bless them.’

I move to Maami’s body. She looks a mess. Her clothes have ripped and her skin wears fresh wounds. They’ll never heal now. I comb my fingers through her hair and wipe the earth and blood from her face. Then we roll her into the ground. Khail hands me a bottle of vodka and I pour it over her. He strikes a match and throws it into the grave. We move a few feet away.

Khail takes my hand, ‘Amina, I’m sorry.’

‘Uh-huh.’

We pass the remaining vodka between us. After four swigs I cough.

‘Khail. Planet One called.’

He passes the drink and cracks his knuckles. ‘The company selected you.’

‘How did you know?’ I don’t sound excited.

‘I always knew they’d take you. You’re a diversity goldmine, the golden token.’ He draws lines in the sand with his toes.

I swallow the dryness that takes my throat down to my stomach. ‘You can come, you know? We could get married. Then they’d have to allow you to come with me.’

‘No, Amina.’

I snatch the bottle from his hands and drain it. ‘Fuck you, Khail!’

‘Okay.’ He pulls me towards him till his mouth is a fan on my lips and I can taste the vodka on his tongue. I close my eyes and let our lips touch. I pull away and touch his hand.

‘Why won’t you do this for me? Would it be so bad?’ I reach for his face, stroking his cheekbones and jawline. ‘We don’t have anything left here.’

I throw the bottle into the fire. Khail steps away from me.

‘Amina, they’re going to dress you up, tell you to bat your lashes and dance. And after the party they will lock you up in a beautiful prison and tell you it’s a castle. How can you take this offer after what they did to your father?’

‘Then tell me what to do?’

‘I can’t. I love you, but I can’t.’

‘You won’t come with me, you won’t tell me what you want.’

‘I want you to be free, Amina.’ He points at the grave fire. The air smells like cooked meat. ‘For the first time ever there is nothing holding you down. You can leave. We can leave Eko. There are still liveable places on Earth, protected parts. It’ll be hard, but we can get in and be safe. Don’t give your freedom to the kind that killed your father.’

I stare into the dwindling flames. This is what my world is, people waiting to be consumed by fire. One day fire will fall from the sky and kill us all.

Khail pisses vodka into the sand nearby. Already we are dropping from dehydration, from poor oxygen, from exhaustion. What is he so adamant about staying?

‘I’m going,’ I shout at his shadowy form in the darkness. ‘I will not wait for fire to claim me.’

The pale doctor asks me to draw Khail’s face. I tell him I’m better with my mouth than my eyes and hands. He nods and asks me to paint Khail with words. I tell him about the consistency of his fura, how whenever I ground the balls they ended up clumpy. His fura was always fine and mixed with thick yoghurt where I used milk and sugar.

I tell him about trailing Khail around the market. How I watched his long black neck crick under the weight of cement and bricks until it became a permanent hunch. How I gasped the first time I saw him shirtless; he had skin like raw crude, beautiful and firm, but patched with red from sunburn and healed wounds. I did not know it was possible for a person so dark to hold so much colour.

‘Khail is tall,’ I say to the Pale doctor. ‘His chest used to be wider but he lost a lot of weight. His hugs are amazing. He smells like water.’ I know how that sounds, but it’s what I think of when he hugs me. I feel that same consistency of water running across stone, wearing down, smoothing edges. ‘He’s so smart. He taught me a lot about history.’

‘Where is Khail now?’ the Pale doctor asks.

‘Earth.’

‘Hmmn. Have you been able to stay in touch since you moved?’

‘Not really.’

‘If you saw him, what might you say to him?’

‘That I’m sorry I left.’ That I want him to tell me he understands so I can stop feeling pepper in my blood every time I think of him.

‘What was Khail’s capacity in your life, Amina?’

‘There’s no earthly word that would do justice to our bond.’

‘He must have been very special.’

‘He is, Dr Atiku.’

Whenever I meet with Dr Atiku, he greets with a swivel of his chair and a smile. I wish I knew what his real face looked like. His doctor face is too much like mine. We both have deep grey eyes and straight noses. Where mine tapers off to the left a little, his stays firm and ends above the divide on his top lip. Our top lips are dark while our bottoms are pink. We are both always wearing polite smiles. I barely see his teeth. He wears pink often. I admire that in a man.

My husband remarked on the same thing the day he dropped me off at my first appointment. ‘It’s weird but you kind of look like your doctor.’

‘I thought I was supposed to look like you. People in love starting to meld into each other and all.’

He laughed and kissed my head. ‘Yes, but you never smile.’

‘I am literally always smiling.’

‘No. Your teeth never show. Mine are always on display.’

At our first session, I told Dr Atiku that my blood felt off. ‘Can you describe what that feels like?’ he asked.

‘There’s a lot of itching sometimes, a lot of heaviness. I feel heavy all the time.’

‘The heavy feeling could be attributed to the gravity shifts; the itching could be an atmospheric response. Maybe you haven’t quite taken to your new environment.’

‘No, it’s not that. I don’t think so.’

‘Amina, you can say anything here, it’s confidential. The same legal framework on Earth applies here.’ He chuckled, ‘For now.’

‘I think maybe I miss being around Others. I’ve never been in such an overwhelmingly Pale place before.’

‘Oh?’ He leaned back and tucked a strand of straight yellow hair behind his ears.

‘Yes. I had this person back home. He used to say he never supported Others moving planets. He said we’d move here and Pale people would enslave us all over again.’

The doctor crossed his legs.

‘No one here makes jokes like that,’ I said and sighed. ‘He was kind of right. I feel like I’m in a bubble.’

‘Amina, a percentage of Forma consists of Others. Surely there must be associations and the like?’

‘No one tells me or invites me.’

He blinked fast, three times.

‘I’m sorry.’

‘Please don’t apologise.’

‘Sorry yeah, not sorry. I just … I don’t know.’

‘Yeah, that tends to happen. Give yourself some time. How long have you been here?’

‘A year and a half in Earth time.’

‘Okay, well I’d like you to schedule a follow-up session. I think together we can find the source of your internal burden.’

I laughed quietly. ‘I like that description. Thank you, doctor.’

On the way out I saw an Other in a cleaner’s uniform coming out of the laboratory. The corner of her cart hit me as we passed each other. ‘Sorry,’ she mumbled.

‘Ba Masala,’ I replied in my father’s language.

Her head jerked up and she regarded me. I smiled. ‘In a gaida. Hello.’ Her eyes flickered across my nose to my eyes, wide like hers, grey unlike her black. Her eyes scrutinised my face, my butter-coloured skin, an unholy hue of Pale and Other. Then she scurried away.

Chet’s pale friends, Cherry and Brett, are over for dinner. Cherry is stunning with a curtain of jet-black hair that reaches her waist. She and Brett have perfect teeth. She blushes when Brett winks at her in public. Brett works for Chet; they both left Earth when they were very young.

Cherry likes my new ‘do’. I’ve braided my hair and twisted the front and sides into knots so it resembles a crown. ‘God, Amina!’ She tugs at a loose braid and gushes, ‘My hair could never do that. If only.’

Chet mouths sorry and squeezes my hand under the table. I smile and turn to Brett and fondle his hair. ‘God, Brett, what lush curls you have. If only my hair could do that.’

Chet coughs into a napkin, Cherry’s hand slides from my hair, Brett swallows four tablespoons of soup without pause.

After dinner I teach them how to do the Wo, a dance from my father’s family.

Brett sits it out and mixes drinks. ‘For after,’ he says. Cherry nails the part where we have to dip low. Chet manages a weak side shuffle. Neither of them can get their hands to angle the way they should. Chet transitions to wobbling. He takes a seat near Brett. Cherry and I practice for fifteen more minutes before she raises her hand.

‘I don’t know, Amina. I’m just not as rhythmic as you.’

I walk to Brett and take a cocktail from him, down it, and return to the centre of the living room.

‘Honey, turn the music up a little, please.’

The drink is not a strong one, but it’s mixed with some of the medication the doctor prescribed to me. Mood regulators, he called them. The music is a line to Earth, it’s a new song but the beats feel familiar, something I’ve lived to, moved my feet to.

I’m so close to Earth now. Even gravity feels different inside this song. I shimmy till I’m squatting, pop my back, then sidle up. I twist my waist into a deceptive eight, and I do it again. I don’t hear the applause till Chet stops the music. The lethargy rushes back and I exhale.

I do a shy bow and walk into Chet’s open arms.

‘Mine, ladies and gentlemen.’

Cherry and Brett stand up and applaud. ‘Amazing! Just amazing!’ After they’ve gone, Chet pulls me by the waist towards him till my leg is in the middle of his legs. I touch his hair—one of my favourite things about him—the same salt and pepper my mother had. Long. I push it from his forehead and eyes.

‘I still can’t believe you’re mine.’ He inhales and kisses me. ‘You’re so fucking sexy, even Brett and Cherry couldn’t stop looking at you.’

He leans in again. I’ve gotten used to his small lips. He nibbles my bottom lip and I giggle. I remember the first time we kissed. Even though I welcomed the affection, I experienced a momentary confusion when I didn’t feel something full pushing back on my lips. There’s nothing to bite, I’d thought.

I kiss him back. Fair trade. Thin lips are a good trade-off for the privileges of being sponsored by him. We’ve come a long way from our first frail encounters. I’ve learnt to hide the worst of my anxieties from him, to serve him sexually, emotionally, to be a living fantasy he can show off. And in return I am here, pampered, and not back on Earth waiting to drop and mesh with all the other abandoned dead bodies.

I pull away from his kiss, tracing a nail across his side. He smiles.

‘I wouldn’t be anywhere without you, my darling.’

‘You are the most beautiful, most exotic girl on the planet. And I love you,’ he says and kisses my forehead.

Dr Atiku is wearing pink again today—two buttons of his shirt undone,—and grey pants.

‘How many Others have you met, doctor?’ I ask.

‘Does it matter?’

‘Yes. Please humour me.’

‘I don’t know.’

‘Okay. Can you count them on two hands?’

He looks down. ‘Yes.’

The day Earth ends, we gather at home with Chet’s friends to watch the satellite feed. Nobody sits. Everybody is afraid of distance; we stand with barely an inch between us. I count three Others: a driver, a nanny—domestic staff like my father was—and there is a mixed child like me, holding her Pale mother’s hand. Where is her father?

I see blue Earth, green Earth, white Earth. From one corner, orange sidles over the tapestry. The orange magnifies till it covers a quarter of the globe, then half. I remember my first drawing as a child. I drew the Earth and coloured it white and black. ‘Why?’ Baami asked.

‘For you,’ I pointed to the black. ‘For Maami,’ I pointed to the white. Now there is no other colour. It plays in slow motion, this ball of orange, receding and pushing the black away around it.

A voiceover punches through the hypnotic pyrotechnic display: ‘We were unable to get any footage from the ground due to the level of heat destruction. As of this moment, three thousand people have been successfully transported out of the Earth’s atmosphere. They have set course for Forma and will arrive in seven months, Earth time.’

Another voice cuts in. ‘We will now observe a moment of silence for the lost planet.’

When everyone bows their heads, I leave the room. There is sand inside my bones. I stagger into the closest bedroom and lie down on the bed. As my head touches the pillow, everything fades into static. Chet’s voice making the tsk tsk sounds. Everyone’s faces, twisted in instructional sympathy. For most of them, the only roots they can trace back to the fallen planet are in books and computer drives under the ‘extended family’ tab. The family that matters to them, they are all here, safe and well-fed, unsweating. Drops swim from my eyes to my neck. My head feels heavy, my face hot. I close my eyes and see Khail, blurry at first, then he gains a higher resolution. I inhale deeply. The apartment disappears and Khail and I are on the Ikoyi bridge, sitting at its centre where the bridge collapsed, our feet dangling into darkness.

Khail touches one finger and another to my jaw; strokes my cheeks before turning my face to his.

‘Sometimes I still think I hallucinate you,’ he says. He moves his hand from my face and swings his leg across the crack in the bridge. A hissing sound comes out of it. The sound spreads around us; it might be coming from the myriad homeless bodies bunched in corners, blanketed in the orange glow of streetlights.

‘It’s possible I only exist in your head. You have the worst life,’ I say.

I crack an eyelid. The apartment comes back. Lava seeps from my eye and I close it again.

No more bridge. Just me and Khail, falling into the crack below.

I stop falling. Khail doesn’t.

‘Come with me!’ I shout. He keeps falling away from me. Lava flows from my other eye. My body burns.

I see fragments. Khail’s eyes, Khail’s lips. Khail laughing and glitching in my head.

Lava runs down my face the way I imagine it fell to Earth, swallowing everybody. Swallowing Khail.

I’m not sure when Chet enters the room, I only feel a cold introducing itself to my skin in the shape of his chest. I feel a straight line of hairs on his stomach as they press into my spine. I feel my arms forced apart and his arms replace them across my chest. His hands fold over my heart.

‘Amina, Amina, Amina,’ he says.

My blood is thick and orange and pours out of me. A smell like Maami’s rotting body takes my nose. The static in my head is a macabre orchestra of screaming and crying, the stray prayers of the about-to-be-dead. I open my mouth but all I can do is croak as all my fluids and energy drain from me.

Chet holds me, calling my name. ‘Amina, Amina, Amina.’ He won’t let me tip over into the crack. He cleaves to me till a new sun breaks through the guestroom’s curtain and all of Earth is gone from me.

~~~

- Alithnayn Abdulkareem is a development practitioner and writer based in Washington DC. She writes mostly opinion articles and personal essays, with the occasional short story to keep things interesting. An alumnus of Chimamada Adichie’s Farafina writers’ workshop, she has been published by Quartz, Ozy, Brittle Paper, Wasafiri, Transition, ID: New Short Fiction from Africa, and others.

~~~

Publisher information

dis• rup • tion /dɪsˈrʌp.ʃən/ [noun] Disturbance or problems which interrupt an event, activity, or process.

This genre-spanning anthology explores the many ways that we grow, adapt, and survive in the face of our ever-changing global realities. In these evocative, often prescient, stories, new and emerging writers from across Africa investigate many of the pressing issues of our time: climate change, pandemics, social upheaval, surveillance, and more.

From a post-apocalyptic African village in Innocent Ilo’s ‘Before We Die Unwritten’, to space colonisation in Alithnayn Abdulkareem’s ‘Static’, to a mother’s attempt to save her infant from a dust storm in Mbozi Haimbe’s ‘Shelter’, Disruption illuminates change around and within, and our infallible capacity for hope amidst disaster. Facing our shared anxieties head on, these authors scrutinize assumptions and invent worlds that combine the fantastical with the probable, the colonial with the dystopian, and the intrepid with the powerless, in stories recognizing our collective future and our disparate present.

Disruption is the newest anthology from Short Story Day Africa, a non-profit organisation established to develop and share the diversity of Africa’s voices through publishing and writing workshops.

Edited by Jason Mykl Snyman, Karina M Szczurek, and Rachel Zadok.

One thought on “[The JRB Daily] [Exclusive] Read ‘Static’ by Alithnayn Abdulkareem, 2nd Runner-up in the 2019/20 Short Story Day Africa Prize”