This week, The JRB is publishing the three winning stories from this year’s Short Story Day Africa Prize.

The winners of the 2020/21 Short Story Day Africa Prize were announced on Monday. This year’s winner is Idza Luhumyo from Kenya, for her story ‘Five Years Next Sunday’. Zambian writer Mbozi Haimbe earned 1st Runner up for her story ‘Shelter’, and Alithanayn Abdulkareem of Nigeria was 2nd Runner with ‘Static’.

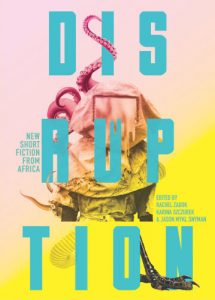

The winners will receive prize money of $800 (about R11,400), $200 and $100, respectively, and their stories, along with the rest of the longlist, will be published in Disruption: New Short Fiction from Africa, due out from Catalyst Press in September 2021.

Today, we’re sharing the full text of ‘Shelter’. Read yesterday’s story, ‘Static’, here, and keep an eye on The JRB tomorrow to read the winning story, or sign up here to receive all three stories in your email inbox on Friday.

~~~

Shelter

Mbozi Haimbe

1st Runner-up of the 2019/20 Short Story Day Africa Prize

I turned up the volume on the radio as the DJ’s voice interrupted the flow of Zed Beats. What now? Another road closure due to unstable tarmac? Protests in the city centre due to another hike in mealie meal prices? It was always something, and never something good.

‘Apologies for disrupting your top twenty countdown.’ The DJ’s smooth, deep voice was more suited to dropping sweet nothings than issuing fake apologies. ‘Our friends at the Zambia Meteorological Centre have sent out an amber warning for an incoming dust storm. All areas of Lusaka are affected. That’s a dust storm, bantu banga. Stay in, stay safe.’

Great. Where was I supposed to find a dust shelter at such short notice? August was the month for dust storms, not January. But here we were, dust instead of rain right in the middle of the wet season.

The music came back on, an upbeat tune pumped with rapping.

I glanced in the rear-view. My baby was still asleep, safely strapped in his car seat. Safely and baby both being relative. Although approaching four, Isaiah was still very much the baby I thought I’d never have. As for safety, that was yet to be seen with this storm brewing.

The traffic slowed down. Routine for morning rush hour on Great East Road. Less routine was the number of motorists committing traffic violations by making dodgy U-turns. Stay calm, Malindi, I told myself. Stay calm.

Heedless, my heart emulated the quick pace of the pumped music.

I’d been on my way to work via Isaiah’s nursery. I now activated the satnav embedded in the upper right corner of my windscreen and searched for the nearest dust shelter. Six red balloons appeared on the map of search results. The closest of these was at the university. I discounted the university shelter as it would be crammed with students. The second closest was near the House of Parliament, which was surrounded by shopping malls. That shelter would likely be full too.

I voice-dialled my husband while executing one of the illegal U-turns.

Wezi picked up immediately. ‘I was just about to call you. Mulikuti? Where are you?’ That thread of anxiety unmistakable in his voice. ‘Are you still at home?’

‘No, we already left. We’re on Great East.’

Wezi’s sharp intake of breath echoed in the confines of the jeep.

I tried to reassure him with, ‘We’re on our way to the shelter near the airport.’

‘Airport, Lindi, no. It’s too far away. Why not return home?’

‘Manje traffic. Better I just rush to the airport, it will be quicker. Plus there’ll be less people at that shelter compared to the ones in town.’ I gunned past an overloaded minibus. ‘What of you? Are you inside?’

‘Me, I’m almost home now. I’m safe. Don’t worry about me.’

‘Okay, honey. I’ll keep you posted.’

I slowed down for a speed camera but stepped on the accelerator again as soon as I was clear. I rarely flouted traffic regulations. But a red-gold hue now tinged the sky, the gold in the dust particles reflecting the sun and creating a shimmering effect. Very pretty to look at. A different matter when the acidic dust touched exposed skin or invaded vulnerable airways. The scientific community was still trying to figure out how the dust, originating in the Sahara, had become acidic and managed to colonise vast swathes of the globe. Some pointed at eco-terrorism. Others posited that Earth was fighting back against humankind’s destruction. Earth was angry, and she was ridding herself of her bipedal burden. My own views flip-flopped between the two camps. On some days, I felt certain the dust was manufactured in a lab. On other days, like today, the angry Earth theory seemed spot on. The music cut off again, a heavy pause before the deep-voiced DJ said, ‘Hello, listeners. Muli bwanji? I’m fine myself, but please do me a favour, ayi? Get inside. Stay inside. That amber warning is heating up to red. And now for the latest offering from our very own Saulani Vincent with ‘Ka Sweetie, Ka Gelo’.’

I sped past the next speed camera without so much as tapping on my brakes. The vehicles going in the opposite direction, west, had now stalled completely, and impatient honking filled the air. The smell of burnt rubber permeated the interior of my vehicle. I slapped at the console to switch to recycled air rather than have the aircon filter external air. It didn’t make much difference. The burnt-rubber smell clung to the lining of my nostrils.

Vehicles zoomed past me. A check in the rear-view showed a steady flow catching up to me. My pulse skipped as my mobile phone rang. I answered it via the in-car system.

‘Wezi, hi.’

‘Where have you reached now?’

I glanced at the satnav. ‘I’m twelve kilometres from the shelter. Should get there in about fifteen minutes, tops. Have you arrived home?’

‘Yes, I’m inside. I’ll stay on the line, though.’ His voice, tight with anxiety, accelerated my already racing pulse.

‘I’m using the radio for updates. It mutes when I’m on the phone.’

Wezi sighed. ‘How’s Isa doing?’

I checked. Two big brown eyes stared back at me. Suddenly a stone wedged in my throat.

‘Lindi? Malindi, are you still there?’

‘Where else would I be, Wezi? Just …’ I gulped down a calming breath as Isa whimpered at my raised voice. ‘Sorry. I’m sorry. Please let me call you back in five.’

He ended the call. I focused on the road. Bright green synthetic grass carpeted the roadside. It was the same almost everywhere in the city. Whether in public spaces or private yards, synthetic grass and concrete covered the ground leaving no space for bare earth. Road signs cropped up at intervals, most of them reminding citizens to ‘Keep Lusaka Dust-Free’. I had to resort to acid-resistant syntho-turf about two years ago myself, when a bad dust storm killed my lawn and contaminated the soil below. People were now abandoning their cars on the jammed westbound carriageway. They streamed across the bright green strip of turfed land that separated the carriageways to flag down cars. Some tried their luck in the neighbourhoods flanking the road, banging their fists on firmly closed doors. We all used to take in stranded strangers. Until the storms started lasting several days and mealie-meal prices limited our charity to friends and neighbours. ‘No, no, no!’ I swerved to avoid a pedestrian. Slammed on my brakes as another ran out in front of my car. ‘Are you crazy? Be careful!’

Isa was crying now, his screams needling under my skin. I threw him a glance over my shoulder, helpless, and resumed driving at a crawl. Losing time. Slowed down by the pedestrians clogging the road. My palms were sweaty on the steering wheel. My back too, warm moisture collecting in the crack of space between my skin and the leather seat.

The dust sensor on my console flashed red. I kissed my teeth at it. What could I do? I was already on my way to a shelter. What more could I do?

‘It’s okay, Isa. No more crying.’

People at the side of the road were strapping on face masks and protective glasses as they walked. The more prepared among them zipped on their hooded, government-issued protective dustcoats, which were beige and ankle-length. I pulled into a layby.

I hadn’t done everything I could.

I dug out my emergency kit buried in a compartment under the passenger footwell. Then hauled Isaiah, car seat and all, over onto the front passenger seat. ‘It’s okay,’ I kept murmuring. ‘It’s okay.’ He’d stopped crying but his eyes remained wide with alarm. Even a child could tell the discrepancy between my assurances and the red-gold sprinkling across my widescreen.

Heart thumping and fingers fumbling, I wrestled Isa into his dust overall with attached hood and mittens. Made of two layers of material with an alkaline gel between them, it was designed to withstand light to medium showers. All safety gear was designed this way. Full-face mask and respirator secured to Isa’s face, I pulled on my overall and exchanged my low-heeled pumps for boots from the emergency kit. I was breathing hard and lathered in sweat by the end of it, having wriggled and contorted in the limited space behind the wheel, big as I was.

A tap on my window.

Three figures huddled outside. School kids, judging from their rucksacks and uniform collars just visible above the neckline of their dustcoats. I popped the locks on the back doors. The teenagers jumped in, a couple more appearing from the dust-mist and hopping in as well. I pulled the hood of my overalls low on my brow. Sure I felt a sharp prickling there from the dust riding in on the heels of my passengers. ‘Close the doors,’ I said, muffled by my mask. ‘Fast-fast, we go.’

‘Zikomo, Ba Auntie,’ they chorused, equally muffled. ‘Thank you so much.’

Dust obscured the sun, plunging the morning into a false evening. I rejoined the traffic. Slow-moving, but at least it wasn’t at a standstill. Had I been gifted with psychic abilities to predict a sand storm in January, I would have been prepared with specially adapted tyres. As things were, I had no idea how long before my tyres started to contribute to the burning smell. We had snow last July. A huge anomaly for this part of the world, but then weather anomalies were becoming the norm these days. The snow fell like icing sugar and formed fluffy clumps wherever it landed, spreading a white, sound-eating blanket over the ground. The dust fell in the same way; ate up sound in the same way. Fluffy red-gold clumps formed on my windscreen quicker than the wipers could brush them off. I leaned forward, gripping the steering wheel so hard I felt my arms would shatter from the tension. Fear coated the back of my throat, corrosive as the acid I was fleeing. Isa sniffled beside me. With the full-face mask and respirator, his sounds of woe had a menacing Vaderesque quality. The ringing phone overlaid Isa’s sniffling, to my relief.

I pulled my mask off. ‘Hi, Wezi. We’re fine. You?’

Pause.

‘Wezi?’

‘So, you’re not at the shelter yet?’

Wezi’s voice was carefully neutral. I felt for him, I did. His family out in the acid, nothing he could do about it.

‘Almost there, honey. Eight kilometres. Plus, the traffic’s speeding up again.’

It wasn’t a lie. After the roundabout, the airport road was straight, exceptionally well tarred and fast. It helped that we were now on the city’s outer limits, which saw much less traffic as a rule. I picked up speed. The dust no longer settled on my windscreen due to my momentum and the rising wind. Adrenalin flooded my system sending chills through me. I stepped on that accelerator. The jeep surged, engine rumbling.

‘You need to lockdown in the basement, Wezi.’

‘After you reach the shelter.’

Our house, like others built in the last five years or so, had a dust-proof basement. Wezi, Isa and I would already have been shut in there by now if I were home. He was taking an unnecessary risk. I looked out at the passing fields.

‘We’re there. We’ve reached the shelter. I’m just pulling in.’

‘For real?’

I nodded, the fields affecting me more than I’d have imagined. They used to be green when I was a little girl. Not bright synthetic green but the lush colour of nature. Fields of maize or sometimes wheat, or pastureland with herds of grazing cattle. There also used to be vast areas of untouched bush along this road: long golden grass, tall trees with gnarled branches and emerald leaves. Now those places were barren ground. Waiting for the red- gold to fall on them and contaminate them, mutate them into acid plains. And they would spread, acidifying more fields across the country. No amount of protesting over mealie-meal prices could make maize grow in acid plains. These once fertile fields of my childhood were today only good for syntho-turf, concrete and high-rise housing. A project the council was already working on, if the architect’s impression on the upcoming billboard was to be believed. A bicycle lay abandoned under the billboard, and then another farther along the road. Both bikes were piled high with blackened bags of malasha, charcoal made from felling and burning trees. I thinned my lips, at once annoyed by the destruction and amazed there were any trees left to plunder.

I must have made a disgruntled sound, because Wezi said, ‘What’s wrong?’

‘Basement now, please, Wezi. You’re giving me blood pressure.’

‘Ah, imwe naimwe.’ He laughed softly with a wealth of affection. ‘Is it me or the storm affecting your BP?’

I also laughed, with the same affection warming my chest. ‘Stay safe.’

‘Yeah. Stay safe, too,’ and Wezi cut the call.

I overtook the car ahead as it rolled to a stop, its tyres flat and smoking. Sediment covered the tarmac, and dust devils rose from the fields. Twisting in tornado shapes as though dancing in welcome to the red-gold. I cut a glance at the satnav to check how much further. An error message glowed on the frozen screen.

Satellite signal lost.

‘Okay.’ I exhaled. ‘Okay.’

‘Sorry?’ one of the teens in the back asked.

‘Who needs a satellite, eh? We’ll just follow the traffic.’

Good plan. Apart from the fact that, one by one, the vehicles ahead limped to the side of the road with their tyres punctured.

Another car slowed down. I overtook it.

The tyre icon on my console flashed; I had a puncture. I kept going though my steering wheel pulled to one side.

But it was harder to persevere when a series of thuds shook the car roof.

‘What was that?’ asked one of my passengers.

The answer came in the form of another thud. This one on my windscreen, leaving a smear of blood and feathers. Nausea hit me. I hugged Isa to my side with one arm, telling him, ‘Don’t look, baby. Please don’t look.’

I could feel his tremors through the two layers of my insulated overalls. My own hand trembled on the wheel as birds fell from heaven. Denting my roof and cracking my windshield. The teenagers in the back were mute, but we communicated our horror as surely as if we were screaming.

The radio crackled with static. ‘Bantu banga, excuse me for yet again disrupt—’

I switched off the radio with a jab of my finger. Had it been playing this whole time? Those pumped up beats? The world was ending and Saulani Vincent was complaining about his Ka Sweetie. A red flash on my console, another punctured tyre. I accepted the inevitable. Even if I were to manage to keep going on the remaining two tyres, there wasn’t enough sunlight piercing the dust canopy. Not enough rays reaching my car’s solar panels.

And to confirm it, the console threw more flashing at me. A cable with a plug on the end of it. Console speak for: you’re low on power, please find your nearest charging station.

Soon, the car decelerated of its own accord. I guided it to the side of the road, engaged the handbrake. Bent my forehead to the steering wheel, my breathing stuttering as I tried to pull my thoughts together. Wait the storm out in the car?

No. The cracked windscreen wouldn’t hold under any more battering.

I touch-dialled a number. Held my breath until a rushed voice answered, ‘Hello? Malindi? Please tell me you’re all okay. I tried to reach you but your line was engaged. Are you inside, I can hear like, like … are you outside? Oh my—’

‘Mum. Mum. Mummy, slow down, we’re fine. I just wanted to check how you are that side.’

‘Us here tuli kabotu.’

My parents and younger siblings were fine, thank God. I ended the call and spoke to my passengers. ‘We run the rest of the way.’

Mask back on, I released Isa from the car seat, and hugging him tight, pushed the door open.

The car had been insulating us. Out here, the vicious wind roared. Slammed into me, flinging hard particles of mutated Sahara sand that stung on contact with the exposed parts of my face. You saw them on the streets, people with pitted foreheads and cheeks, the pockmarks tiny and discoloured. Sandpox. I’d be one of those people now. I held Isa against my chest as I staggered under the force of the wind. My teenage passengers were already far ahead. A couple more seconds, and I couldn’t tell them apart from all the other people fleeing the storm in their dustcoats.

The thing was not to sweat or cry. Fluid activated the acid quicker than dry skin.

I couldn’t help sweating. The tears, I held in. They were a hot lump in my throat, shimmering in my eyes. Because about three, maybe four hundred metres ahead was the domed, grey shape of the dust shelter. Like all shelters, it stood on high ground. My arms burned from carrying Isa. My back ached from my own extra weight, feet stumbling as my melting soles slipped on the gritty tarmac. A quick glance over my shoulder: the dust devils were gathering speed behind me. So close. I was so close to the shelter now. Gasping for breath, I powered up the incline. But it seemed to me I was running on a backward moving travelator.

‘Nearly there, Isa.’ I clutched him tighter as he started to slip from my arms. ‘Wait for us! Don’t close the door, please!’

The wind snatched my muffled plea away. Not that it mattered. The shelter doors were automated and rigged with dust sensors. They would shut if the dust saturation exceeded threshold levels. Deserted vehicles lined both sides of the road. Some of the cars hadn’t had their annual protective veneer upgraded and now lay prey as acid disintegrated their paintwork into plumes of stark white smoke. It wafted across my path and restricted my visibility, cut me off from the world. It was just me and Isa snared in smoke and swirling sand. Someone came running towards us. One of the teens I’d given a lift. He doubled up against the wind and raced closer, arms outstretched.

I understood.

I was moved with gratitude, heart swelling.

‘Thank you,’ I said, handing Isaiah over. ‘My husband is called Wezi Mtonga, just in case. Now, go. Run.’

He nodded, and sprinted back to the shelter. I wasn’t too far behind him, my will intact even though I lumbered, ungainly. Isaiah and the teen disappeared into the shelter. A man and a woman came and stood in the doorway, urgently beckoning with their arms: run!

A sob caught in my throat as the doors began to close. A red light flashed above the doorway, siren cutting through the wind’s roar like a deadly blade. I wouldn’t make it. My God, I would die out here.

I extended my arms in silent pleading. The man and woman strained forward, grabbed a hand each and yanked me through the diminishing doorway.

I wasn’t supposed to cry. Still too dangerous. But the sobs overcame me, tears seeping beneath the edge of my protective glasses to burn my cheeks.

‘Stop it. Stop that. You’ll ruin your pretty face.’ The woman sprayed my face with neutralising solution, which cooled the burning in an instant. ‘Take the glasses off and close your eyes.’

I did, took the mask off too, and she doused my face with the solution.

‘How far along are you?’ she asked.

I glanced around the crowded reception hall. ‘My son, where’s my … Isa! Isaiah!’

‘Calm down, we’ve taken him to the creche. He’s quite safe.’ She dipped her gaze to my belly. ‘When is your baby due?’

Slime ran off my overalls where the red-gold sand had penetrated through to the alkaline layer. I stripped off the overalls, said, ‘I have another ten weeks to go.’

She pursed her lips. Then turned and called across the hall. ‘Dr Agnes, I’ve got one for you here.’

‘I’m coming!’

Dr Agnes showed me to a little room off the reception hall. She checked my vitals, performed an ultrasound scan, and gave me a kind smile. ‘You’re both fine,’ she said. ‘This is an excellent shelter; we’ll all be fine.’ I slid off the examination table and buttoned my blouse.

The place stank of acid-burnt rubber. The occasional drumming of birds falling on the roof reverberated through the shelter. Most of the people in here were covered in sandpox.

Maybe we were all fine right now. But for how long?

~~~

- Mbozi Haimbe was born and raised in Lusaka, Zambia, where she lived until her mid-twenties. Her story, ‘Madam’s Sister’ won the Africa region prize of the Commonwealth Short Story Prize 2019, and a 2020 PEN America/Robert J Dau Prize. Mbozi has a Masters in Creative Writing from Cambridge University. She was awarded a Develop Your Creative Practice award by Arts Council England in 2020, and is currently working on her debut novel, an Afrofuturistic story based on the Makishi masquerade traditions of the North-western people of Zambia. A qualified social worker, Mbozi lives in Norfolk, UK, with her family.

~~~

Publisher information

dis• rup • tion /dɪsˈrʌp.ʃən/ [noun] Disturbance or problems which interrupt an event, activity, or process.

This genre-spanning anthology explores the many ways that we grow, adapt, and survive in the face of our ever-changing global realities. In these evocative, often prescient, stories, new and emerging writers from across Africa investigate many of the pressing issues of our time: climate change, pandemics, social upheaval, surveillance, and more.

From a post-apocalyptic African village in Innocent Ilo’s ‘Before We Die Unwritten’, to space colonisation in Alithnayn Abdulkareem’s ‘Static’, to a mother’s attempt to save her infant from a dust storm in Mbozi Haimbe’s ‘Shelter’, Disruption illuminates change around and within, and our infallible capacity for hope amidst disaster. Facing our shared anxieties head on, these authors scrutinize assumptions and invent worlds that combine the fantastical with the probable, the colonial with the dystopian, and the intrepid with the powerless, in stories recognizing our collective future and our disparate present.

Disruption is the newest anthology from Short Story Day Africa, a non-profit organisation established to develop and share the diversity of Africa’s voices through publishing and writing workshops.

Edited by Jason Mykl Snyman, Karina M Szczurek, and Rachel Zadok.

6 thoughts on “[The JRB Daily] [Exclusive] Read ‘Shelter’ by Mbozi Haimbe, 1st Runner-up in the 2019/20 Short Story Day Africa Prize”