The JRB presents an excerpt from Olivette Otele’s African Europeans: An Untold History, which was recently shortlisted for the Orwell Prize.

Olivette Otele

Jacana Media, 2021

African Europeans: An Untold History

Read the excerpt:

O poet, hold not dear the people’s acclamation;

The eager shouts of praise will quickly die away.

Cold-hearted crowds will mock, and fools prate condemnation;

But be thou calm and firm, and proudly keep thy way.

These words were written by one of the greatest Russian writers and poets, Aleksandr Pushkin, in ‘To the Poet’ (1830), which advises a fellow poet, as a warning as much as an encouragement, to keep writing and stay faithful to their craft while trusting their skills. Pushkin was born into old noble families on both his mother and his father’s sides. His links with Africa could have gone unnoticed were it not for a slightly darker complexion and features that differed marginally from those of his fellow Russians. His mother was descended from Scandinavian nobles, but his maternal great-grandfather was General Abram Petrovich Gannibal (or Hannibal), a recognised figure in the history of Russia.

Gannibal was kidnapped from West Africa when he was eight years old. He was enslaved, and ended up in the service of a Serbian count who took him to the court of Tsar Peter the Great. Peter took an interest in young Gannibal and decided to have him as his godson. He then sent him to France to be educated. Many opportunities followed for Gannibal, and he embarked upon a military career, rapidly rising through the ranks. His African ancestry came to be known and valued when, in a letter addressed to the Senate in 1742, he stated that he came from a noble family in Africa. After petitioning the court and the Senate to be granted the status of a nobleman, Gannibal succeeded in reaching the highest social status he could have hoped for. His life was not wholly successful; his first marriage was disastrous. However, his second marriage with Christina Regina Siöberg, a noblewoman whose ancestry encompassed both Brandenburg and Scandinavia, proved to be happier. They had ten children, including a son called Osip who went on to have a daughter named Nadezhda. She was Pushkin’s mother. The 1742 letter has prompted a historical investigation to determine from which place in Africa Gannibal originated. In the letter, he had written that he was born in a city called Logone or Lagone and that his father was the monarch of two other cities. Historian Dieudonné Gnammankou followed several trails and eventually found out that Gannibal was born in Logone-Birni, a town located near the Logone River in the far north of Cameroon. The research was supported by several Russian bodies, such as the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

Gannibal’s great-grandson, Pushkin, never shied away from his family’s African heritage. In the first edition of his novel in verse Eugene Onegin (1825), he warns his readers that he plans to write a biography of his black ancestor. As Cynthia Green notes, the novel ‘contains one of his most famous references to his own mixture of Russian and African heritage’ in the passage:

It’s time to drop astern the shape

of the dull shores of my disfavour,

and there, beneath your noonday sky,

my Africa, where waves break high,

to mourn for Russia’s gloomy savour,

land where I learned to love and weep,

land where my heart is buried deep.

He had prior to that adopted the moniker afrikanets (‘the African’), and his unfinished historical novel was based on his great-grandfather. He had entitled it The Moor of Peter the Great. Modern Russia is proud of both Pushkin’s and Gannibal’s achievements. They are commemorated on statues and stamps, and Pushkin’s work has been reinterpreted through further literary productions, music, films and so on, in Russia and across the world. Pushkin never visited Africa. Both he and Gannibal were resolute European Russians who embodied several histories and reminded their contemporaries of intellectual crossroads, the legacies of education and the tumultuous and brutal histories of conquest.

Other stories of Afro-Russians very often related to transcultural exchanges, Pan-Africanism and the investments of many African intellectuals and politicians in communist ideology. Cameroon and a few other countries sent students to be educated in Russia during the period that followed the independence of most African nations in the 1960s. The expectation was that those students would return to their countries to help shape policies and initiate social change. Many of those who left belonged to families with strong ties to the government, and they were welcomed back with open arms and enviable positions as civil servants in the upper echelons of society.

What is important here is to connect past and present in order to understand how contemporary Europe, Russia included, deals with these legacies and common histories. It appears that the history of engagements and collaborations has been forgotten, as stories of the former Soviet Union are relegated to the past in public discourse. The rise of ethnonationalism in Eastern European countries, with a dangerous emerging tendency to promote monocultures, does not leave room for African Europeans to embrace and celebrate their multiple heritage. Testimonies of assault and racial discrimination are numerous in twenty-first-century Europe. However, the election of Peter Bossman as the first black mayor in Eastern Europe in 2010 seemed to signal a new departure and brought hope to many. Bossman was born in Ghana, but due to the political situation in the country he had to leave when he was in his twenties. He studied medicine and years later settled in Piran in Slovenia, where he set up his own private practice. Bossman was criticised for not speaking Slovene, the country’s official language; language is often a measuring tool for integration as well as part of an exclusionary arsenal wielded by anti-immigrant groups. Nonetheless, Bossman stated that he had never experienced racism and truly believed that Slovenia was on the path to great positive change. Class may blur discriminatory boundaries, as Bossman’s experience is in stark and puzzling contrast with the voices of African Europeans across Europe.

For those who were born in Eastern European countries, have dual heritage and only grew up with a European parent, finding one’s mark in a society that distrusts difference is a daily fight. From Nina, who grew up in Slovakia and was raised by her Slovak mother, to some of the 5,000 or so Afro-Polish who live in Poland, interaction with the majority group is twofold. It is either a sexualised and exoticised relationship in specific public spaces such as dance clubs and arts centres, mainly between black African men and white Eastern European women, or an exoticisation of dual-heritage women by fellow countrymen and country-women, who display both fascination with dual-heritage bodies and unexpected racist attitudes towards people of African descent. Violence in every shape and form is part of these exchanges. The European Commission’s reports about racism in Eastern European countries such as Latvia, and its recommendations for combatting the problem, often indicate that the arrival of new migrants has unsettled local populations. In many instances, however, these new arrivals have occurred at a relatively low number and cannot convincingly explain racial harassment and racially motivated attacks. Stories about Russian and Eastern European football fans attacking black supporters during international tournaments continue to dominate the news. Racism against black people in sports is not exclusive to these countries, but threats, bodily harm and even deaths have led several players to advise supporters to avoid Eastern European countries. Life for those who reside there remains difficult in many instances.

~~~

- Olivette Otele is Professor of the History of Slavery at the University of Bristol and Vice-President of the Royal Historical Society. She is an expert on the history of people of African descent and the links between memory, geopolitics and legacies of French and British colonialism.

Publisher information

As early as the third century, St Maurice—an Egyptian—became leader of the legendary Roman Theban Legion. Ever since, there have been richly varied encounters between those defined as ‘Africans’ and those called ‘Europeans’. Yet Africans and African Europeans are still widely believed to be only a recent presence in Europe.

Olivette Otele traces a long African European heritage through the lives of individuals both ordinary and extraordinary. She uncovers a forgotten past, from Emperor Septimius Severus, to enslaved Africans living in Europe during the Renaissance, and all the way to present-day migrants moving to Europe’s cities. By exploring a history that has been long overlooked, she sheds light on questions very much alive today—on racism, identity, citizenship, power and resilience.

African Europeans is a landmark account of a crucial thread in Europe’s complex history.

‘This is a book I have been waiting for my whole life. It goes beyond the numerous individual black people in Europe over millennia, to show us the history of the very ideas of blackness, community and identity on the continent that has forgotten its own past. A necessary and exciting read.’—Afua Hirsch, author of Brit(ish)

‘Fascinating … One of the book’s great pleasures is its cast of memorable characters [and] though this is a work of synthesis, it’s an unusually generous and densely layered one.’—The Guardian

A brilliant, important and beautifully written book that forces us to think about the past differently.’—Peter Frankopan, History Today Books of the Year 2020

My wife was from the French Caribbean and during the year we spent in Ceaucescu’s Rumania, our best friends were two anglophone students. K was a Zulu who had escaped from Rhodesia to Scotland where rather than wait for a place at Dundee University, foolishly opted to take up his United Nations’ scholarship in Moldavia. L was a Malaysian of Chinese descent. The cement to our friendship was the freedom that speaking English gave us.

Because I am white, the police assumed I was Rumanian and seeing my wife and me together in the street, would promptly arrest us, only to apologise obsequiously on discovering I taught at the university. This was nothing compared to the treatment meted out to K who would be beaten up when local yobs realised he was accompanying a Rumanian girl.

Olivette Otele writes: “language is often a measuring tool for integration as well as part of an exclusionary arsenal wielded by anti-immigrant groups.” Well I remember an occasion when all four of us were on the bus. Seeing a lady weighed down with many bags, I relinquished my seat which she took readily. Yet as soon as she heard our talking in English, she jumped from her seat like a scalded cat.

One Saturday night we were in a smart hotel with some French speaking Africans drinking beer from teapots – it was past the legal drinking hours. When the time came to go home, I suggested we took a taxi and to a man the West Africans started laughing. Taxis would never stop for blacks, they informed me.

The saddest story concerns Luca. At the time many of us thought – unjustly – he was a spy for the Securitate, the Rumanian secret service; he taught French in the university and appeared totally impervious to the fear that submerged everybody, Rumanians and foreigners alike. (More than three decades later, he sent me via Facebook, an unflattering Securitate report he had scoured from the internet. It concerned my imperialistic and unsocialist behaviour in repeating off-colour Rumanian jokes.) One day I was chatting with Luca in the university staff restaurant when a postgraduate student turned up. An Algerian scientist, S always claimed that the régime back home in Africa had inoculated him against the injustices of Ceacescu’s repression. No sooner had S – a Muslim – sat down with us than Luca stood up, leaving my African friends and me with the explanation that he could not remain at the same table as ‘uncivilised people’.

Forty years later I travelled to Malaysia and spent a joyful time with L, now a retired generalist, and his wife in Kuala Kangsar – (he’d been educated at the school where Anthony Burgess once taught). K returned to his homeland, now Zimbabwe, married and then emigrated to Australia where he still works as a doctor.

For anyone wanting to hear Ms Olivette Otele discuss the AfroCaribbean composer Chevalier de Saint-Georges, here is the link:

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p09b3p7x

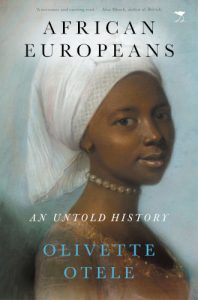

Where did she get the photo on the cover of her book? The woman on the cover of her book is in Louisiana history as a woman named Maria Theresa Coin Coin. She had children by Claude Thomas Pieare Metoyer. Her parents came from Togo Africa as slaves. She was born in Louisiana? And she is my Great Grandmother from the 17th hundreds in Louisiana?