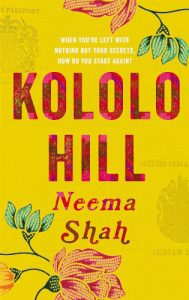

The JRB presents an excerpt from Neema Shah’s debut novel Kololo Hill.

Kololo Hill

Neema Shah

Picador, 2021

Outside the train station in Kampala, the roads were three times as wide as those in her village. They stopped briefly at Motichand’s dukan, which did indeed seem to have anything you could ever need and many things you’d never want, but she couldn’t take it all in. How far away her father was, her brothers, her home. Everything was different, strange, the buildings, the air. Her husband.

The house was centred around an open yard. The single-storey building was painted pale green like the inside of a pea pod. Running along three sides of the yard were a kitchen, a walk-in storeroom, a sitting room with two wooden armchairs, three bedrooms and a small enclosed space with a tap for morning ablutions. It was a larger house than the one that she’d lived in for the past year back in Gujarat, crammed in with Motichand’s brothers and mother. This home was bigger than any she’d ever seen. All that space for two people.

‘And this is December,’ announced Motichand proudly, waving his hand towards the man in the corner of the courtyard, as though he was another feature of the house, like a brand-new radio or a stove. ‘Everyone has house boys here.’

December was tall and slim, with a head of thick hair like unspun cotton. He was already too old to be considered a boy by a good few years, closer to her own age in fact, but Motichand had explained on the train that the name ‘house boy’ was the label for all male servants here. December glanced over at Jaya. His rigid brows made him look as though he was annoyed but then he flashed a brief smile, his eyes narrowing into crescents. Jaya pulled her chundri tighter around her face and turned her head away, as she’d been taught to do with all men for the sake of propriety. But she regretted it immediately. It must have made her look stuck-up.

Jaya unpacked a few items in the bedroom she’d share with Motichand, a simple square with two large beds. Separate beds. She didn’t linger, going back outside onto the veranda.

‘Here, I have translated the main things you’ll need, so you can get December to help you with anything you want.’ Motichand thrust a scrap of paper into her hand.

Jaya looked at the paper, a mess of scribbled words written in Gujarati with notes for the Swahili translation.

‘I am going back to the dukan now,’ said Motichand.

‘You are leaving?’ Jaya looked up.

Motichand called out something in Swahili to December, who was sweeping the veranda. He waved his hand in response.

‘Do not worry. He used to look after an English widow for a while, she lived on her own, nothing to worry about. He is most helpful. Most reliable. Back soon,’ Motichand called out, leaving a spare set of keys on a hook and slamming the door behind him.

Panic ran along her spine. He’d left her there with a stranger roaming the house. A Ugandan man. Could she trust him? In Gujarat, she’d never been alone with a male who wasn’t a relative; no respectable woman would be left alone with a man she wasn’t married or related to. What would her father say if he heard about it? What would the other Asians who lived nearby think of her and Motichand? But if there was one thing she’d learnt about her husband in the few weeks she’d spent with him in India, it was that he was oblivious when it suited him.

She turned towards December, who was crouching on the far side of the veranda, sweeping. He looked up: an awkward smile, shy even.

The day passed in a muddle. Either Motichand’s translations or her pronunciation were wrong. When she asked for a saucepan to make chai, December poured water from the copper pot into a saucepan and made the tea himself. When she asked for matches to light the outdoor fire for dinner, he lit the fire himself and beckoned her over when it was ready.

She wanted to shout at him, to make him stop. She couldn’t get used to someone else serving her. Certainly not a man. ‘Revah deh,’ she said to him, the Gujarati words sounding strange in this new setting, and of course December looked at her in confusion. He got up and poured another cup of water, raising his eyebrows in the hope that he’d got it right.

Jaya drank the water, even though she wasn’t thirsty.

*

Each day, December brought home food from the market, using the money Motichand gave him. Some measly tumeta, a paler red than she was used to, along with a few stringy pieces of chicken and a gunny sack of millet that he’d cradled in the crook of his neck all the way home. She looked at the food but lacked the words to ask December why the money provided so little. Now she realized she lacked the words to ask Motichand either; her mother had made it clear: you couldn’t involve men in household matters, nor question them when things went wrong.

She longed to speak to someone she knew, to ask their advice. At least when she was in Gujarat, Jaya had been able to see her own family once or twice, even though she’d moved to another village after her marriage. It was the tiny details about each of them she missed the most. Her youngest brother gleefully pulling their Kaki’s little pigtail and running away; the string of soft sighs her father made when he fell asleep, as though the very act of sleep itself was exhausting. She even missed the people that were on the periphery of her life in the village. The people she’d never worried about leaving, people she’d assumed would always be there, their lives intertwined forever.

*

In the evenings after dinner, Jaya joined Motichand in the sitting room. He knocked back a glass or two of whisky while they listened to the BBC World Service. Even though she couldn’t understand the announcers, Jaya found the muted, crackling English words a comfort, a voice to cut through the loneliness. She asked Motichand about December’s life, where he came from, whether he had a family to support, but her husband had never bothered to ask. Meanwhile, Motichand’s occasional visits to her bed at the end of the evening were as awkward and bumbling as their wedding night had been, but thankfully infrequent.

Motichand’s brothers were supposed to follow him across the black water, the kara pani, as it was known, because the people in their villages said the sea would pollute and wash away your caste. They were supposed to help grow the business, but their letters were full of vague promises to join him, arriving months after they were written, only adding to the confusion. Looking back, Jaya wondered if they knew what she’d later learnt for herself: Motichand couldn’t be trusted with money—it seemed to flutter in and out of his hands like a bird.

Most days, Jaya was stuck at home until Motichand finally returned. The cricket call was often the only thing to keep her company as dusk fell. Wanting to take more control of the household and converse in Swahili, she encouraged Motichand to teach her words whenever he was around. Sometimes, when they went to the newly built temple, Mrs Goswami would teach her a few words, though Jaya learnt to ignore her sly digs about a husband who left his wife alone with a Ugandan man all day. Jaya picked up the names of different foods—mchungwa, ndizi—and found out how many shillings they cost. Her Gujarati was infused with the softness and timidity expected of a woman, an echo of the women she’d left behind in India, but in Swahili she was emphatic and assertive, her vowels rounder, diction stronger, rhythm bolder. She became someone else.

*

‘What does your name mean?’ Jaya asked December. They were in the yard, turning over the chillies they’d left to dry out on her tattered old saris. As the day had gone on, the bright scarlet chillies had shrivelled and darkened, as though they had soaked up the terracotta colour of the earth beneath.

December looked up at her in surprise; their conversations tended to focus on housework. His eyes were streaming; the heat of the sun brought out the fire of the chillies. They scorched the air, burning Jaya’s throat.

‘December. It’s the name of a month, in English.’

‘And it is a common name for people in your village?’ Jaya had assumed it was a traditional tribal name, similar to the way that Indian names were given, according to caste and religion. Yet perhaps it was usual to take the names of the English?

December laughed and wiped his eyes with the back of his arm. ‘It’s not my name, not really. One of the families I used to work for before was English. The little girl said December was her favourite month and they struggled to pronounce my name. Adenya.’

‘A-den-ya.’ Jaya thought it much easier to pronounce than December. ‘Well, we will call you Adenya from now on.’

‘No,’ he said. ‘Call me December, it’s my name at work. Adenya is my family name.’

~~~

Publisher information

‘An impressive, confident debut about family and survival, against the backdrop of a history that is not written about often enough.’—Nikesh Shukla

When you’re left with nothing but your secrets, how do you start again?

Uganda 1972

A devastating decree is issued: all Ugandan Asians must leave the country in ninety days. They must take only what they can carry, give up their money and never return.

For Asha and Pran, married a matter of months, it means abandoning the family business that Pran has worked so hard to save. For his mother, Jaya, it means saying goodbye to the house that has been her home for decades. But violence is escalating in Kampala, and people are disappearing. Will they all make it to safety in Britain and will they be given refuge if they do?

And all the while, a terrible secret about the expulsion hangs over them, threatening to tear the family apart.

From the green hilltops of Kampala, to the terraced houses of London, Neema Shah’s extraordinarily moving debut Kololo Hill explores what it means to leave your home behind, what it takes to start again, and the lengths some will go to protect their loved ones.

One thought on “‘Call me December, it’s my name at work.’—Read an excerpt from Kololo Hill, the debut novel by Neema Shah”