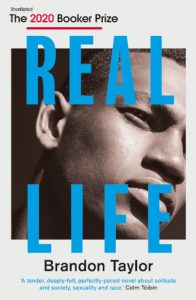

The JRB presents an excerpt from Brandon Taylor’s debut novel Real Life, which was shortlisted for the 2020 Booker Prize.

Real Life

Brandon Taylor

Daunt Books, 2021

~~~

At the edge of the water, stone steps descended to the murky bottom of the lake. They were made from a kind of harsh, unfinished stone that had been smoothed by the water and the foot traffic. There were, two or three arm lengths away from Wallace, other people sitting too, watching the moon rise. And on the distant shore, past where the peninsula, furred with pine and spruce trees, hooked into the lake like a thumb, there were houses raised up on great stilts, the lights in the windows like the eyes of some large birds. Wallace had thought at times when he took the lakeshore path at night, looking through the scrim of trees, that all those houses did look like a flock of enormous birds crouching on the other side. He had never been over there himself, had never had a reason to cross the lake to that rarefied and separate part of town.

The small boats had come in and been set on their racks, draped for the night. The larger boats were taken out farther down, near the boathouse, where Wallace sometimes took walks in the other direction, to where the grass grew wild and the trees were denser and heavier. There was a covered bridge and a family of geese living there. Sometimes, he saw their big grey wings spreading out beneath him as they glided across the water. Other times, he saw them lazily and confidently striding in the shade toward the soccer fields and picnic grounds, like stern game wardens. But at this time of the evening the geese were away, and the gulls had returned to their nests, and Wallace had the edge of the water to himself except for the other anonymous watchers nearby. He glanced at them briefly and wondered what shapes their lives held, if they were content, if they were mad or frustrated. They looked like people anywhere: white and in ugly, oversize clothes, sunburned and chapped and smiling with large, elastic mouths. The young people were long and tan, and they laughed as they pushed on one another. Farther back, the great mass of people spread out over the pier like moss. The water beneath him splashed up a little, wetting the edges of his shorts. The stone was slimy and cool. A band was starting up behind him. Their instruments twanged as they whirred to life.

Wallace hugged his knees and put his chin on his arms. He slid his feet out of his canvas shoes and let the lake wash up to his ankles. It was cold, though not as cold as he had expected or would have liked. There was something slick in the water, something apart from the water itself, like a loose second skin swilling around under the surface. There were stretches of days when the lakes were closed because of the algae. It sometimes secreted neurotoxins that could be fatal. Or harboured parasitic organisms that clasped on to swimmers and sucked them dry, or gave them diseases that caused their bodies to tear themselves apart from the inside. The water here could be dangerous even if you didn’t know it. But there were no warnings posted. Whatever was in the water was not yet at a level thought dangerous to people. The water stank more now that he was close to it, like alcohol, powerfully astringent and chemical.

It reminded him of the black water that had stared at him from the drain of his parents’ sink all those years ago. Black and round, like a perfect pupil gazing up at him, smelling sour, like something gone bad. His father had also kept buckets of still water. I’m saving that, he’d say when Wallace tried to pour it out. Saving it the way one saved old clothes or bottles or pens with no ink or broken pencils. Because you never knew what might happen that would make the trash worth keeping. The water in the buckets was as dark as tar because leaves had fallen from the roof into it and had broken down. Sometimes, he saw the frail brown remnants of the stalks, after all the green had been eaten away. At the right angle, it was possible to see the writhing forms of mosquito larvae as they flitted just along the surface. His father had told him once that they were tadpoles. Wallace had believed him. He had cupped his hands in the slimy water and had squinted close, trying to discern the tadpoles. But of course, they had only been mosquitoes.

Dark water.

There was a knot of tension high in his chest, something hard and coiled. It felt like a black ball stuck to the inside of his lungs. His stomach hurt too. He had eaten nothing but soup all day. The surface of his hunger was rough, like a cat’s tongue. Pressure gathered in the backs of his eyes.

Oh, he thought when he realised what it was: tears.

In that moment, there was a body next to him. Wallace turned, for an instant expecting to see his father’s face, conjured up out of memory, but instead, it was Emma, who had come at last with her fiancé, Thom, and their dog, Scout, a shaggy, happy thing.

She put an arm around his shoulders and laughed. ‘What are you doing over here?’

‘Taking in the sights, I reckon,’ he said, trying to match her laugh.

~~~

- Brandon Taylor’s Real Life was a New York Times Editors’ Choice and shortlisted for the Booker Prize. His work has appeared in Guernica, American Short Fiction, Gulf Coast, Buzzfeed Reader, O: The Oprah Magazine, Gay Mag, The New Yorker online, The Literary Review, and elsewhere. He is the senior editor of Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading and a staff writer at Lit Hub. He holds graduate degrees from the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he was an Iowa Arts Fellow.

Publisher information

Wallace has spent his summer in the lab breeding a strain of microscopic worms. He is four years into a biochemistry degree at a lakeside Midwestern university, a life that’s a world away from his childhood in Alabama. His father died a few weeks ago, but Wallace didn’t go back for the funeral, and he hasn’t told his friends—Miller, Yngve, Cole and Emma. For reasons of self-preservation, he has become used to keeping a wary distance even from those closest to him. But, over the course of one blustery end-of-summer weekend, the destruction of his work and a series of intense confrontations force Wallace to grapple with both the trauma of the past, and the question of the future.

Deftly zooming in and out of focus, Real Life is a deeply affecting story about the emotional cost of reckoning with desire, and overcoming pain.