Whether we have learnt from the story of Dr Abdullah Abdurahman remains to be seen, writes Stephen Langtry. Martin Plaut’s new book marks a ‘partial’ start.

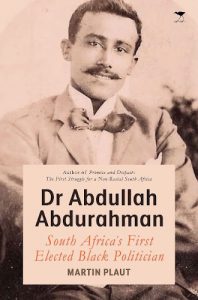

Dr Abdullah Abdurahman: South Africa’s First Elected Black Politician

Martin Plaut

Jacana, 2020

1.

Martin Plaut’s biography of Abdullah Abdurahman brings to the surface the story of a largely forgotten but important figure in the history of South Africa and the former Cape Colony. There is not a lack of information about the life of Abdurahman, and Plaut’s volume includes a fairly comprehensive bibliography. He reminds readers of the works of Mohamed Adhikari (Not White Enough, Not Black Enough, 2005), Crain Soudien (The Cape Radicals, 2019), Gavin Lewis (Between the Wire and the Wall, 1987) and Richard van der Ross (In Our Own Skins, 2015). He also makes particular mention of Eve Wong’s University of Cape Town Master’s thesis: The Doctor of District Six: Exploring the Private and Family History of Dr Abdullah Abdurahman, City Councillor for District Six of Cape Town (1904–1940) (2016). For this assemblage of information alone, Plaut’s book is invaluable.

At the time of his death in 1940, Dr Abdullah Abdurahman (affectionately referred to as ‘the Doctor’) was a highly respected figure. His funeral procession brought the city of Cape Town to a standstill. The ceremony was attended by the Mayor of Cape Town and tributes flowed in from several quarters, including from the Prime Minister, Jan Smuts. It is therefore interesting that less than one hundred years after his passing, the legacy of the Doctor from District Six is in need of resuscitation.

Biographies about popular figures—alive or dead—are a dime a dozen. But writing about someone who was once well known but has now receded into obscurity is a challenge. It is very much like salvaging a sunken ship or excavating an archaeological site. So one approaches this biography about Abdurahman with some excitement, in anticipation of new treasures to be revealed. But one is also curious about why this particular story has been neglected; in the same way that one wishes to understand why a ship sank or why a once majestic structure was abandoned.

In the first quarter of the twenty-first century, South Africa is in desperate need of stories being told—and retold. As someone who is engaged on social media in the retelling of stories from the distant and recent past, I am often surprised at how many people are unaware of large aspects of South African history. Of course, the blame must be placed squarely at the feet of national government, which has neglected the heritage sector—including its transformation and governance—at the expense of a narrow exposition of our history. And with a lack of knowledge of the past, there is a growing body of misinformation to fill the gaps.

Globally, there is an assault on facts of not more than a few days old. The efficacy of this assault grows stronger as the distance between events of the past and our present recollection widens. In few places is this more evident than in present-day South Africa. Just twenty-six years after the official end of apartheid—which was declared a crime against humanity—South Africa is experiencing a rise in apartheid denialism. While the seven volumes that comprise the report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission gather dust, there is a strident effort to deny or minimise the impact of apartheid (and the colonial injustices which preceded it). While these sentiments have always abounded at dinner parties, braais and on social media, they were given greater currency in March 2017, when Helen Zille tweeted while waiting to board an aeroplane:

‘For those claiming legacy of colonialism was ONLY negative, think of our independent judiciary, transport infrastructure, piped water etc

‘Would we have had a transition into specialised health care and medication without colonial influence? Just be honest, please.

‘Getting onto an aeroplane now and won’t get onto the wi-fi so that I can cut off those who think EVERY aspect of colonial legacy was bad.’

More recently (June 2020), she followed up with another Tweet:

‘Lol, there are more racist laws today than there were under apartheid. All racist laws are wrong. But permanent victimhood is too highly prized to recognise this.’

Even in the age of ‘alternative facts’, Zille’s statements were considered too outlandish, and other leaders of South Africa’s largest opposition political party distanced themselves from them. However, these assertions do not stray too far from the official positions of some opposition political parties and bring to light the discomfort that many white South Africans feel during conversations about colonialism and apartheid.

Why do some feel it is so important to attempt to rehabilitate the legacy of colonialism and apartheid? The answer to this question beckons us to pause and reflect on the importance of Plaut’s book.

2.

Shaun Viljoen subtitled his biography of Richard Rive, A Partial Biography. Plaut could very easily have done the same with his work on the life of Abdurahman. His biography is unashamedly biased in favour of its subject: Plaut builds the character of the Doctor of District Six up to such an extent that, I would argue, he brings into question the stature of some of Abdurahman’s contemporaries.

But Plaut’s biography is also partial in the sense of being incomplete. The 218-page volume tends to focus on Abdurahman’s opposition to the formation of the Union of South Africa, which sought to exclude the majority Black population from its political life. This might very well be the most important political work in which he participated. It is certainly the aspect of his life which brought him on to the international stage, taking him to meet high-level players in England and India. But it is just one part of his life.

The book contains only a passing reference to the major contribution Abdurahman made to education for Coloured people. The role he played in the establishment of the Teachers’ League of South Africa, ensuring Harold Cressy’s admission to the University of Cape Town (where Cressy became the first Coloured person to obtain a degree), and the founding of both Trafalgar and Livingstone High Schools—the first high schools for Coloured people—are glossed over.

Interesting information from Abdurahman’s record on the Cape Town City Council are also omitted. Once when he was seated in the council chamber, some of the white city councillors refused to sit next to him. This did not deter Abdurahman from making reconciliatory overtures. In this regard, Plaut neglects to mention, for example, Abdurahman’s vote in favour of the renaming of Maitland Road to Voortrekkerweg in 1938. In response to criticism for this decision, he said: ‘the fact is that non-Europeans stood side by side with the Voortrekkers and their blood was shed freely on the field of battle with the Voortrekkers’. His position on this matter explains some of the negative attitudes towards his memory that have lingered after his death.

Plaut concludes that Abdurahman fell out of favour because he located himself too much in South Africa’s political centre and thus earned the ire of both those on the right and the left. This elevates Abdurahman to the status of Nelson Mandela, who today is considered a sell-out by a radical young Black generation, and (still) a terrorist by recalcitrant white racists.

Indeed, there were strong conservative tendencies in the Cape that were fearful of antagonising the white colonial establishment and the status quo. Abdurahman faced opposition, among others, from John X Merriman (one-time Prime Minister of the Cape) who described him as a ‘pathetic figure’. From within his own community as well, Abdurahman had his detractors, such as FZS Peregrino and NR Veldsman, who hitched their wagons either to British idealism or Afrikaner nationalism and who sought to avoid confrontation by all means in the hope that their compliant behaviour would win concessions for at least some Coloured people.

At the same time, while he was a close associate of some of the founders of the African National Congress—such as John Dube, Walter Rubusana, and Sol Plaatje—it’s clear why the ANC today is not exactly rushing to embrace Abdurahman’s legacy. Though, as Plaut points out, the positions taken by Abdurahman at the time did not differ significantly from the early leaders of the ANC, the author presents evidence that contemporaries such James La Guma—as well Abdurahman’s own daughter, Cissie Gool—accused him of having ‘betrayed his people’ because of his close ties with white liberals.

Having flown under the radar for the greater part of the last eight decades, Abdurahman has escaped some of the vicious criticism that has been levelled against some of his contemporaries, including Gandhi—another of his associates. But Gandhi, of course, harboured strong prejudices against Black (particularly African) people. There is no evidence that this was the case with Abdurahman. On the contrary, the record shows that he worked tirelessly (albeit unsuccessfully) to build bridges between African, Coloured and Indian people in the fight against institutionalised racism.

3.

Abdurahman’s efforts to block the formation of the Union of South Africa were fuelled by his opposition to a political settlement between two white groups—British imperialists and Afrikaner nationalists—to the exclusion of the majority Black population. The Union of South Africa laid the basis for the current political dispensation. It confirmed the borders of the current state—two former British colonies and two former Boer republics. (Interestingly, Afrikaner nationalists wanted to extend the borders to include Bechuanaland [Botswana], Swaziland [Eswatini], Lesotho, and Rhodesia [Zimbabwe]. They were also intent on extending the Boer republics’ policy of disenfranchising the ‘native’ population into these spaces. How different the fortunes of the region would have turned out if they had succeeded.)

The settlement that led to the Union is symbolised today in the three capitals of South Africa, Pretoria, Bloemfontein and Cape Town, established to appease the white Afrikaners and the English, and the two towers of the Union Buildings in Pretoria, which represent the two white groups. The statue of Louis Botha (the first Prime Minister of South Africa) has a place of honour at the entrance to Parliament in Cape Town. This is the same Botha who said:

‘On the native question in South Africa, the first decade was necessary for the consolidation of the Union. The whites … have laid the foundations of, and must continue the erection of, that edifice to make it habitable. Afterwards they would negotiate to see how much room was left for the natives.’

The hope of 1994 was that the inclusion of the ‘natives’ and, for that matter, all Black people (African, Coloured and Indian) in the formal political life of South Africa would magically erase all the history that preceded. This hope was premised on the idea that in exchange for Black South Africans not taking revenge for centuries of oppression, white South Africans would make gestures of restitution. This would have subverted the young Black minister’s concern in Alan Paton’s Cry, The Beloved Country: ‘I have one great fear in my heart, that one day when they turn to loving they will find that we are turned to hating.’ Plaut illustrates how the period after the formation of the Union of South Africa marked the betrayal of Black aspirations by both Boer and British interests. In particular, in 1936, the British reneged on the promise made by King Edward VII in 1909 to preserve the rights of Black voters in the Cape. The lack of goodwill shown by the white minority towards the majority of South Africans is therefore not a recent phenomenon. Even overt quislings such as the Coloured political organiser NR Veldsman did not win any concessions and were cast aside when their usefulness was expended.

Abdurahman emerges as a tragic hero in this tale—and in this biography. He follows all the rules set by white society. He attends one of the best (almost exclusively white) schools in Cape Town. He qualifies as a medical doctor at a prestigious university in Europe. He marries a European woman with whom he returns to Cape Town to set up a medical practice. He is well connected within the white liberal establishment. He opposes the ‘radicals’ of his time and pursues a politics of restrained protests via official means (by petition and dialogue) through his elected positions. In the end, though, all his efforts come to naught. He is rejected. He dies with the Union of South Africa on course to embrace a system that would last for another fifty-four years.

Steve Hofmeyr—an Afrikaner nationalist who moonlights as a musician—famously tweeted in October 2015 that ‘Blacks were the architects of Apartheid’. After reading Plaut’s book one understands why someone like Helen Zille actually has much more in common with Hofmeyr than with Black members of her own political party. Today, the Western Cape (which comprises part of what was once the Cape Colony, and later Cape Province, in which Abdurahman operated) remains largely divorced from the rest of a unitary Republic of South Africa. Public schools that are predominantly white, such as the one Abdurahman attended, still exist—indeed, they thrive—and reflect the same colonial ethos. There is a call, which is growing in popularity, for secession from the rest of South Africa. Realising that they cannot succeed on their own, white supremacists who want an independent Cape appeal to Coloured people to support this call. As during the time of Abdurahman, there are elements in the Coloured community who pin their hopes on white-led parties to restore rights to them that were taken by white people more than three hundred years ago. Whether we have learnt from the story of Dr Abdullah Abdurahman remains to be seen. Martin Plaut’s book marks a ‘partial’ start.

- Stephen Langtry works at Cornerstone Institute, a private not-for-profit higher education institution in Cape Town. He has experience in the public service, education and not-for-profit sectors. Follow him on Twitter.

One thought on “A Cape tragedy—Stephen Langtry reviews Martin Plaut’s new book Dr Abdullah Abdurahman: South Africa’s First Elected Black Politician”