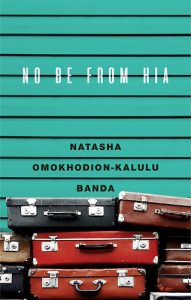

The JRB presents an excerpt from No Be From Hia, the debut novel by Natasha Omokhodion-Kalulu Banda.

No Be From Hia

Natasha Omokhodion-Kalulu Banda

BlackBird Books, 2020

Read the excerpt:

CHAPTER 17

MAGGIE OLUWASEUN AYOMIDE

LAGOS, NIGERIA, 2017

The passengers make a beeline for the double decker RwandAir airbus and the queue curves along the grey tarmac. Once on the plane, they fill each seat—not one space empty. Nigerians on their way to Lagos from verdant, police filled, highly organised Kigali. People have a sense of urgency as they proceed to their seats, no mercy for the lanky man who takes a luxurious walk in the aisles looking for cabinet space for his hand luggage.

‘Dis year I beg, move oh!’ they all say in a chorus.

I take my seat next to a young man who has a face full of scarification. Lines on his forehead, his cheeks, and his chin, all at an angle like upside down Vs. He greets me and tells me he is Nupe—a student from Nigeria living in Uganda. He asks me where I am from, and I hesitate.

A trio of women sit in the row behind us. From the conversation, I can tell that they are on their way from Lusaka to Lagos for miracle prayers at TB Joshua Ministries. The lady in the middle seat is sweating and weak. The other two repeatedly prop her up as she slumps to the floor with fatigue. One lady fastens her seat belt for her and tries to wipe her brow and fan her at the same time. They are speaking loudly, clicking their fingers in the air, asking God to bind all principalities and forces of darkness. They shout, ‘Shatamalata kata brakata rakata rakata rakata! God cover the pilot and his crew in the blood of Jesus, clear the way for them, so that your servant here can be healed by your hand, Ropheka! Give her strength to reach her miracle land for healing.’ I look back at the Nupe boy and decide not to reveal my Zambian identity.

The entire aircraft promptly goes to sleep, completely wrapped in blankets like human cordon bleu, revealing only the tops of their hairstyles and the soles of their feet. I close my eyes and try to remember them.

Memories of a gentle grandmother come fleetingly. We would sit on the fluffy carpet where she would braid my hair in loose cornrows for bedtime. The smell of coconut and shea butter wafted from her soft, cool hands as they danced along the neatly made lines running down my head. The Manhattans in white jumpsuits on the telly singing something about kissing and saying goodbye. Me asking where my mother was and why I could only speak to her over the static of the phone once a week. My grandmother would go around the subject in a way that left me puzzled.

‘Do you know why I like to braid your hair in cornrows, darling?’

‘So, it’s soft in the morning?’

‘Well, yes, honey. But, more importantly, because we should never forget.’

‘Forget what, Grandma?’

‘That we did all the hard work.’

‘I don’t get it, Grandma.’

‘This hair style reminds us of the cornfields. Of the plantations—corn, cotton, and sugar. My people’s people’s people—they had to work the sugar plantations all day in the scorching sun. Cornrows are a style that kept our hair kempt while we worked. It crowned our heads like the kings and queens we are, despite being reduced to less than human.’ At that, I sit upright from my slouch, push my shoulders back, lift my chin, and cross my legs.

‘To make a cornrow, you need all of the hair to join in neatly, row by row—and that’s how we worked—together. It also means, my darling, we all need each other, and it’s the same for our family. Don’t worry, your mother will be home soon.’

My grandfather was never with us physically—at least I don’t remember him there. Not the touch of him nor the smell of him like I did my grandmother. But I remember the story of him—of his presence, his charismatic personality of how gregarious he was. The big man around town, the host of London’s best parties. He now remains a figure in a picture frame laughing with friends, whisky in hand, good looks, and comfort surrounding him.

Finally, we descend, and as the plane falls, my emotions swell and mount. Something opens my entire being like a floodgate. I weep as though someone has died. The feeling is raw, open, cavernous, engulfing. How can the return to a land you barely know be so gripping? The poor Nupe boy is uncomfortable, not knowing which way to look. His scars turn upwards in worry—he offers me a tissue.

We touch down, and I pray for the land of my ancestors to be good to me. That my father will be there and that I will find favour in the eyes of my grandparents. That they will tell me more, help me understand my lineage better. That they will embrace me like they once did. That this void in my heart will finally be filled.

The hostess tells everyone to leave their blankets behind—there is zero adherence to her plea.

At the luggage carousel, I stand next to a gentleman who has just come off the same flight. His shirt announces loudly across his chest that it is ‘100% Genuine Dolce & Gabbana’. I wonder what it would be if it were anything less than the declared percentage. His belt is tight around his waistline, like he’s been struck by the curse of prosperity.

‘I saw you in Rwanda,’ he says in a matter of fact voice, like one who is used to being an authority on any subject.

‘Oh, I see,’ I respond.

He persists. ‘Pardon me, but is that ring real?’ He points at my marriage band.

I nod warily.

‘I think we separated when I went into first class. Me sef, I was coming from Dubai. The first class in that Rwanda plane is actually impressive. You can evun lie down on flatbed.’

I laugh.

The carousel makes complete passes a few times, but our luggage does not reveal itself. He seems to lose his composure.

‘This is ridiculous! First class in Dubai doesn’t treat you like this. First class anywhere else in the world will ensure that they release your baggage first!’ He wipes his brow in frustration. He shifts his weight onto his other leg. ‘Is this your first time in Nigeria?’ he asks me.

‘As an adult, yes, it is,’ I say.

‘Oho, where will you be staying?’

‘Ikeja.’

‘Oh, I see.’ He reaches for his business card and hands one to me. It reads in gold foil: Bola Richards. Not disguising his disappointment, he carries on. ‘Me sef, I live in Lekki. It’s on Victoria Island. Life there is much better than on the mainland. Please get in touch. Perhaps I can show you the country club where I play golf.’

Thankfully, his bag arrives, and he walks away flustered, probably wondering how I could pass up such a chance. My bag arrives shortly, and I grab it off the carousel.

My moment of truth arrives. The one I have been imagining all my life, and now I feel weak with anxiety. What if my father isn’t here to meet me?

‘Hmmm, madam, ooh!’ the passing trolley guy says to me.

I turn around, surprised.

‘What is ya name?’

‘Maggie.’

‘Diaris somtin about you, actually—everytin’ about you. De way you walk, de way you talk, and evun ya name iz beautiful! Diarias a God oh!’ He rolls his eyes pretending to look skywards, as if his prayer had been answered.

I laugh at his boldness. There is no way that would happen in Lusaka. ‘Well, hello, Lagos!’

At the small window, I change Dollars into Naira. A strong aura and a familiar voice, creep up from behind me. ‘Maggie?’ I turn, and it is my loving uncle Tayo.

His hair is worn in long silver dreadlocks secured in a ponytail. He is so skinny; his shoulders jut out of the sleeves of his traditional shirt. His fingernails are brown, like his skin. He is visibly excited; we smile at each other—both unsure where to start.

After a brisk hug but a warm welcome, and an uncomfortable laugh, he escorts me outside. He dramatically chases the trolley boy and walks me outside to arrivals. There stands my father; rounder and fuller than he once was. Laughing eyes behind his glasses. My own, red and puffy, tired from the long night of tears and the flight.

‘Maggie, my baby,’ he says.

‘Daddy.’

We embrace. Strangely, it feels as natural as something we do every day.

We all head to the pickup area, teeming with people of various shapes and sizes. The midday sun sits right above us, hot and low, the air enclosing, constricting like a four-sided cage. A policeman, possibly an army man, approaches and makes jest with my father. His arms are so long, right down to his knees. His hands look murderous, extraordinarily large and turned inwards. His red beret and black uniform are scary, but his laugh is warm and syrupy.

We get into an old Jeep, and the hot leather receives us. The aircon is broken, and we drive away from Murtala Muhammed International Airport onto the highway. My father shows me the cantonment area in Ikeja where Uncle Tayo’s family lived—they talk about the great parties they would have there during his summer holidays. On the mainland, a crisscross of electric lines sag and hang low from the many poles. The greyish smog like air sits close, and my father says it has something to do with Lagos being at sea level. I don’t believe him.

The sound of pressed hooters is persistent, with only short bursts of silence between. A droptop Bentley materialises, as though out of a hip-hop video, with a man in Medusa sunglasses and a thick beard. He has a woman with beige skin in the passenger side. The street hawkers try to jump into his back seat while they admire the big oga. A younger one almost succeeds.

‘Woz wrong with you now? U dey craze?’ His big beard moved along with his words.

‘Oga, you go buy cold water?’ They try to appease him.

‘You wan die? Dem dey follow you from house, if u no comot from hia I go slap you!’ He makes a move for his glove compartment, and they scatter away. He curses them—their mothers, and their children, and their children’s children.

I look around in wonder. Okadas and three-wheelers zoom past us. Danfos carting their passengers blare a cacophony of Drake and Davido. Their conductors hang out of the doors of the moving motors—defiant to death. Passengers jump on and off the buses without the vehicles coming to a complete stop. Bank brands are lined up everywhere, shouting for attention, orange GT Bank, blue Ecobank, red United Bank for Africa.

Finally, we turn off the main highway and onto a slip road, followed by the sound of the Imam calling all brethren to prayer. The bumpy dust road boasts suya roasts packed into newspaper funnels. The tomato grinder down the road puts his onion, garlic, tomato, and bell peppers into his welded funnel and turns the wheel while his liquid gold pours into waiting yellow buckets below. His crotched singlet and wrapper are a befitting outfit for the heat and the work on which he concentrates single mindedly. His customers line up, ready to collect their pre-mix for tonight’s stews.

My father explains that the grinder has lived opposite them for many years and that his tomato grinding business has sent all his children to school abroad. The grinder’s wife disappears into their home behind a lilac coloured curtain at the main door entrance. Right next to them stands an opulent mansion completely fenced in with barbed wire carefully placed along its perimeter. The house occupies its entire floor space, so it almost touches the barbed wall. It towers above its humble neighbour, pointing forwards as if to say, ‘Judge not,’ but rather to look the opposite direction, at what I will come to find is our own duplex.

The gate is opened by a skinny man-cub with fuzz for a moustache. He can’t be over fifteen. Ironically, his name is Youngharry. But then I remember that it is not uncommon to have teenage workers in this part of Africa. The squeaking sound of hot stones against rubber announces our arrival into the compound.

At last, the sound of angry car horns is no more. There is a different noise here. Generators, televisions, faceless voices haggling. We go upstairs to my grandparents’ room.

~~~

- Natasha Omokhodion-Kalulu Banda is a UK-born Zambian of Nigerian and Jamaican heritage who lives in Lusaka. She has been published in the African Women Writers (Afriwowri) ebook anthology Different Shades of a Feminine Mind, and featured on African Writer Magazine for her story ‘To Hair is Human, To Forgive is Design’ (2018). She was published in Short Story Day Africa’s anthology Hotel Africa (2018). The manuscript of her novel No Be From Hia was selected as a Graywolf Africa Prize finalist in 2019.

~~~

About the book

A homecoming tale of a family brought together by migration and torn apart by tragedy and secrets.

In a search for identity, love and acceptance—two ordinary girls travel from London to Lusaka to Lagos in order to save their family and discover their destiny. Meet the Ayomides and the Kombes: Zambian–Nigerian–Jamaican powerhouse families brought together during the post-colonial migration of the nineteen-sixties to the UK, and later separated by death, divorce and betrayal.

Scattered between London, Lusaka and Lagos, only the new generation can save this family. Maggie Ayomide and Bupe Kombe are cousins on either side of the world who couldn’t be more different. Zambian–Nigerian and Zambian–Jamaican, both yearn for their disbanded family to reunite. When Bupe leaves Brixton to go to secondary school in Zambia, she brings light and disorder to Maggie’s world. However, the girls are hindered by dark family secrets such as the mysterious death of their late grandmother, and Maggie’s missing Nigerian father.

One thought on “‘We touch down, and I pray for the land of my ancestors to be good to me’—Read an excerpt from No Be From Hia by Natasha Omokhodion-Kalulu Banda”