The JRB presents an excerpt from Safari Nation: A Social History of the Kruger National Park by Jacob Dlamini.

Safari Nation: A Social History of the Kruger National Park

Jacob Dlamini

Jacana Media, 2020

Read the excerpt:

Melancholy Travel

In a short story from 1981 titled ‘The Haunting Melancholy of Klipvoordam’, writer Miriam Tlali tells of a group of six Soweto residents (three adults and three children) who decide to spend the last day of 1979 and to bring in the New Year by camping at a holiday resort in the homeland of Bophuthatswana. As the unnamed narrator tells the reader, her friends Donald and Pauline, a married couple, came up with the idea. Donald and Pauline are clearly old hands at the business of camping, as we can see from the camping paraphernalia that fills their Volkswagen van. Don and Paul are special beings, says the narrator:

The like of them in a place like Soweto should be protected from extinction; they should be honoured and revered. They are like a rare and endangered species of God’s creation. They are among the few who still strive to bring about order where there is only chaos and despair. In the jumbled shattered existence of the Soweto Ghetto, they hanker after the sustaining force of mother nature. For does nature’s eternal seasonal cycle not offer the propagation of new life in place of the withering and dying and hence hope for the future?

To get to the resort, the campers drive through Soweto, past the affluent and tree-lined white suburbs of northern Johannesburg, and through what the narrator calls a scantily populated countryside. As the campers approach Bophuthatswana, the narrator says:

One would have expected that we would arrive at some border post, some line; a river or a bridge, at the end of which would be stationed a pair of stern-looking uniformed guards. That these honourable gentlemen would be wearing labelled epaulettes over their proud shoulders, or even medals on their lapels. I had looked around expecting to see sign-posts along the road reading: ‘Welcome to the Sovereign State of Bophuthatswana.’

Yet we knew that by … taking a turn away from the smoothly-tarred road onto the gravel one, we had in fact departed from the so-called ‘white’ South Africa. We had left behind all the comfort that goes with that part of this land. We were now part of the so-called Bophuthatswana self-governing black state, having automatically relinquished all that was of merit. The whole transition had been as easy as taking candy from a child. Just like that. No lines of demarcation had been drawn, no signs, nothing.

It would have been redundant. We knew it; our bodies felt it. We were all aware that the one world had come to an end and a new one had begun. The dry dust, the thorny scrub on either side of the uneven road had warned us.

Having made the transition from ‘white’ to ‘black’ South Africa, the party arrives at the resort, ‘the first time I had the honour of visiting a “black” recreational area in a so-called independent state in my own country and naturally I was curious.’ The narrator proceeds to examine the different trees and observe the birds and animals in the resort. She is clearly a fish out of water here. None of what she finds in the resort is known to her. She has no prior knowledge of the wild. She has to be schooled. ‘There was ever so much to learn,’ she says. But she also learns that the resort is an incomplete construction site dotted with ‘poor skeletal left-overs.’ The resort’s previous white owners were on the verge of building an electricity plant but abandoned their plans when the government created Bophuthatswana in 1977. ‘The whole business of the poverty—the ever-present legacy always so readily bequeathed to the ‘honourable’ inheritors of the so-called free black states. Who bothers about freedom in a deprived desert anyway, I wondered.’

Despite her disappointment, the narrator is still able to enjoy herself. She had got away from the noise and the dancing of Soweto. Disturbed by the sounds of the wild, she plays the music of Brook Benton to calm her nerves. As the campers count the hours toward the dawn of the New Year, they talk about the death of loved ones and the imminent independence of Zimbabwe. Early the next morning, as the six campers enjoy the break of dawn—what the narrator chooses to call by the Sotho-Tswana name mafube ‘because to my mind, in the English medium in which I am writing, no word that I can think of describes adequately the whole mesmerising excellence of the break of dawn than “mafube”, especially when seen in the clear open emptiness of unspoilt nature’—a melancholy dark figure emerges from the thicket. The man looks like he is bearing the world’s problems on his shoulders. ‘The man was very likely trying to escape from the helplessness of a lifetime of unfulfilled aspirations—an existence where hopes and dreams remain forever a receding mirage.’ But the man is also there to enjoy mafube. He is there to witness the break of dawn. Oppression and thwarted aspiration are no bar to an appreciation of nature.

Distilled into this poignant four-page story are some of the key themes of this book—not to mention twentieth-century South African history—from the fraught mediation of the divide between the urban and the rural, to the black and the white worlds, to the negotiation of the apartheid atlas, to a material engagement with homelands, to an affective sense of place, to the politics of black life in apartheid South Africa, to the meaning of Africa’s decolonisation for black South Africa, to the social distinctions and class divides within South Africa, and to the use of African languages to articulate black appreciations of nature. To be sure, Tlali’s is a fictional account, but in that fiction lie contested histories and histories of presence.

If Tlali offers an imaginative account of the black middle-class experience of the wild, Njabulo Ndebele provides more critical—but not necessarily historically accurate—reflections on the existential state of black tourism in South Africa. These reflections are not, as I show above, beyond challenge, but they are good to think with. Reflecting on a visit to a game lodge, Ndebele says that black visits to game lodges amount to the ‘experience of cultural domination in a most intimate way.’ This feeling is most acute during game viewing. He writes:

It is difficult [for blacks] not to feel that, in the total scheme of things, perhaps they should be out there with the animals, being viewed. Caught in a conversation with their white fellow refugees, brought together with them by an increasingly similar, stressful lifestyle, they can engage in discussions which bring out both the artificiality and the reality of their similarity. The black tourist is conditioned to find the political sociology of the game lodge ontologically disturbing. It can be so offensive as to be obscene. He is a leisure colonialist torn up by excruciating ambiguities. He pays to be the viewer who has to be viewed.

Ndebele says blacks are conditioned to find game lodges ‘ontologically disturbing.’ These lodges began life as extensions of white power in South Africa but had become, by the end of the twentieth century, places of white refuge from the stress of living in a black-ruled country. Everything is still in place in a lodge, from the amenities to the mute black workers. This is troubling to the black tourist:

Until very recently, one of the distinguishing features of the game lodge was the marked absence of black tourists, but now they are beginning to show up in steadily increasing numbers. Being there, they experience the most damning ambiguities. They see the faceless black workers and instinctively see a reflection of themselves. They may be wealthy or politically powerful, but at that moment they are made aware of their special kind of powerlessness: they lack the backing of cultural power.

Ndebele offers a powerful account of the black experience in postapartheid South Africa, where affluence cannot protect members of the black elite from racist humiliation. But Ndebele’s account also offers a powerful reminder of the cultural and political safaris, not to mention the class struggles going back at least a century, that sought to make South Africa a home for all: a home where pioneers of the black elite such as DDT Jabavu worried about soil conservation, thinkers like Thema fretted over the meaning of the KNP, and theorists of black nationalism such as Anton Lembede thought about ‘trees and their value to human beings.’ But elite blacks did not and do not have a monopoly on safari.

~~~

- Jacob Dlamini is an assistant professor of history at Princeton University and is a qualified field guide. He is the author of Askari: A Story of Collaboration and Betrayal in the Anti-Apartheid Struggle, for which he won the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award, Native Nostalgia, and more recently, The Terrorist Album.

~~~

About the book

‘Safari Nation is about the beauty of the Kruger National Park, as well as the ugly side of that beauty. The book will have succeeded if it helps readers already familiar with the park renew their love for the park, and if it drives readers not acquainted with the park to fall in love with it. But, for both sets of readers, that must be critical love. It must be love rooted in history, not some cant about a pristine wilderness or, worse, some unspoiled Africa somewhere. To help preserve the KNP for posterity, we have to come to terms with its past while helping to prepare it for an uncertain future.’—From the Introduction by Jacob Dlamini

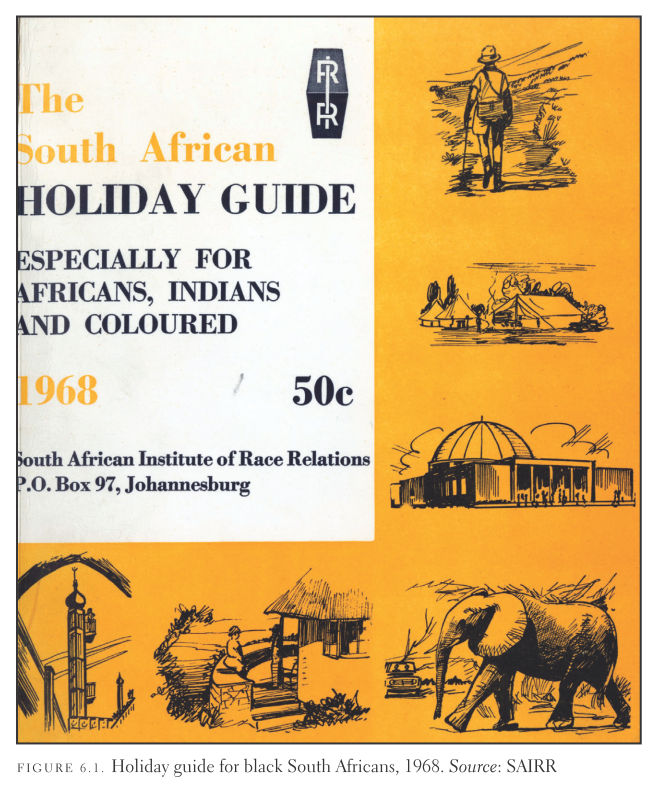

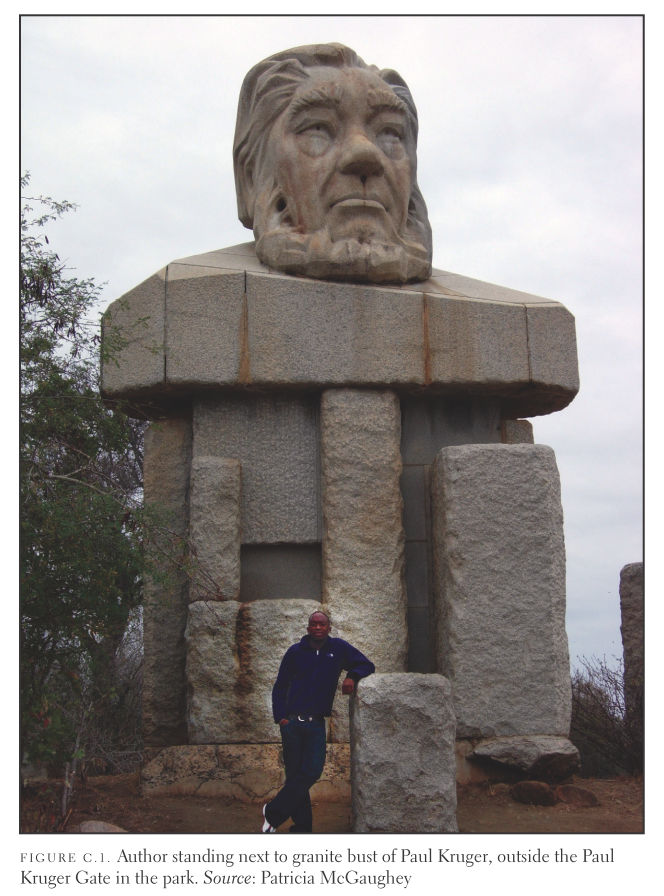

The Kruger National Park is South Africa’s most iconic nature reserve, renowned for its rich flora and fauna. According to Dlamini, there is another side to the park, a social history neglected by scholars and popular writers alike in which Black people (meaning Africans, Coloured people and Indians) occupy centre stage.

Safari Nation details the ways in which Black people devoted energies to conservation and to the park over the course of the twentieth century – an engagement that transcends the stock (Black) figure of the labourer and the poacher.

By exploring the complex and dynamic ways in which Black people of varying class, racial, religious and social backgrounds related to the Kruger National Park, and with the help of previously unseen archival photographs, Dlamini’s narrative also sheds new light on how and why Africa’s national parks—often derided by scholars as colonial impositions—survived the end of white rule on the continent.

Relying on oral histories, photographs and archival research, Safari Nation engages both with African historiography and with ongoing debates about the land question, democracy and citizenship in South Africa.

One thought on “‘Oppression and thwarted aspiration are no bar to an appreciation of nature’—Read an excerpt from Jacob Dlamini’s new book Safari Nation: A Social History of the Kruger National Park”