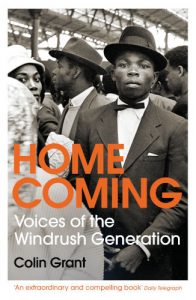

Colin Grant’s Homecoming: Voices of the Windrush Generation is an important and valuable text that has captured the voices that enriched British society for decades without proper recognition, writes Adekeye Adebajo.

Homecoming: Voices of the Windrush Generation

Colin Grant

Vintage, 2020

1. A griot of a people’s trials and tribulations

In 2008, Jamaican–British historian Colin Grant published the most comprehensive contemporary biography of Jamaica’s most famous Pan-African prophet, Marcus Garvey: the magisterial, meticulously researched Negro in A Hat. Just over a decade later, we have Grant’s new oral history, Homecoming: Voices of the Windrush Generation, based on more than one hundred interviews, archival recordings, and memoirs of Caribbean immigrants in Britain. The anthology makes for a further attempt by Grant to trace his Caribbean roots; and to give voice to the hopes, achievements and struggles of Caribbean immigrants who came to Britain as part of the ‘Windrush generation’. These exiles are collectively named after the ship HMT Empire Windrush, which transported many of them in the first year of migration, 1948—the year of the British Nationality Act that granted British West Indians citizenship and the right of residence in the United Kingdom.

Grant is thus a griot and chronicler of his people’s trials and tribulations in a foreign land—albeit one that many Caribbeans had previously considered the ‘Mother Country’. His ‘excavation of the past’ includes talking about his own working-class parents, Clinton ‘Bageye’ and Ethlyn Grant, and the autobiographical tales in the book are some of the most interesting. Colin grew up in an unhappy council house in unfashionable Luton, with his father often feeling humiliated and slighted by British racism, and his mother consistently expressing frustration at having abandoned her middle-class lifestyle in Jamaica—complete with uniformed servants—to struggle in a hostile Britain. The author’s parents reflected the divide within the West Indian community: nostalgic ‘dreamers’ forever thinking back to the sacrifices they had made in leaving their islands, and ‘realists’ who did not look back but preferred to focus on the harsh realities of adapting to life in Britain.

Between 1948 and 1963, an estimated 300,000 Caribbean immigrants from Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago, Guyana, St Kitts and Nevis, Antigua and Barbuda, and other islands, arrived in Britain by sea and air. (As Black African countries gained independence from Britain from 1957 onwards, the Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1962 severely restricted immigration from Africa and the Caribbean, the former subjects discovering anew that the wealth of the metropolitan had never, in fact, been common.) Jamaicans constituted seventy-five percent of these immigrants. The exiles went, in the main, to London, Leeds, Luton, Reading, Manchester and Birmingham. It was essential that Grant capture their rich stories before the generation disappeared. He thus interviewed people from a diverse background of countries, professions, and generations: teachers in Croydon, welders in Leeds, nurses in Manchester, bus drivers in Bristol, motor workers in Luton, seamstresses in Birmingham, seamen in Ipswich, slum landlords in Notting Hill, Calypsonians in Salford, dockers in Tiger Bay and Carnival Queens in Chapeltown. These are all people who have been largely invisible to their British hosts, whose lives have never been properly documented, whose significant contributions to the making of contemporary Britain never properly recognised. Grant notes that Caribbeans have partly contributed to their own anonymity, through secretiveness and an obsession with maintaining a low profile, borne of not wanting to attract attention to themselves. He is particularly keen to reverse the marginalisation of women immigrants who were part of the exodus from the start. Finally, the book also includes interviews with white Britons, to capture their impressions of the West Indians in their midst.

2. Great expectations: Anglophilia and a clash of cultures

Britain had introduced slavery into, and colonised, twenty Caribbean countries for three centuries. Many Caribbean citizens thus grew up on a staple diet of British education and culture. They embraced the Mother Country and were told that they were members of the Commonwealth, entitled to carry British passports. They also wore their Sunday best, sang ‘God Save the King’ and ‘Rule Britannia’, and unfurled the Union Flag every Empire Day on 24 May. They read Shakespeare, Dickens and Walter Scott; they recited classic British poems by Pope, Kipling, Wordsworth and Chaucer; their history was about how Churchill had vanquished Hitler; their geography was about British seas and shires; and their economics was about Bristol iron and Sheffield steel. West Indians were also exposed to Ealing comedies, Laurence Olivier’s acting, Noel Coward dramas, and pantomimes like Puss in Boots and Cinderella. They played cricket, football, rugby, tennis and bridge; they learned English country dancing and the waltz; they attended churches with British priests; they admired British gentlemen in bowler hats and umbrellas; and many ate an English breakfast.

The Caribbeans stood up to sing the British national anthem in their local cinemas before the film started. It was as if they had no history, no culture, and no literature of their own. Many never made the connection between the widespread destitution and poverty on their islands and British slavery and colonialism. Indeed, many adopted deferential and subservient attitudes to white people: for them, Pax Britannica had only brought modernisation to their countries. Anglophile Caribbean citizens thus wholeheartedly imbibed British culture, despite the widespread professional and social discrimination baked into British colonial rule on their islands. As Waveney Bushell, a Guyanese immigrant, noted: ‘We were indoctrinated into feeling that Britain was the place in the world … I felt everything English was the best.’

Rarely did these Caribbean citizens read about their own history or study the work of local writers. They had a romantic attachment to England long before they stepped ashore on the Mother Country. The textbooks that they read, including Nelson’s West Indian Readers, were all imported from Britain. Many of their objects of material pride—cars, clothes, shoes and suits—were made in England. British banks proliferated in their countries. Grant notes, of the thorough belief in the mission civilisatrice of empire that obtained on the islands, ‘The bodies of West Indians may have been in the Caribbean, but their heads were in British clouds.’ Or, as Jamaican journalist Vivian Durham put it, with perhaps more poignancy: ‘The ambition of every black Jamaican in those days was to be a white man.’

3. Bleak House: Slavery and its modern legacy of racial discrimination, limited opportunities and hard times

Trinidadian scholar-politician Eric Williams demonstrated in his seminal 1944 study Capitalism and Slavery that the main beneficiaries of the transatlantic slave trade had been the ‘plantocracy’ of British merchants and planters in the Caribbean, operating out of ports such as Bristol, London and Liverpool. Between 1680 and 1786, over two million African slaves were shipped to British colonies in the Caribbean in vessels with names like Enterprise, Fortune and Lottery. This trade laid the foundations of contemporary British industry and banking, and had widespread support among the monarchy, the church, politicians and the general public. After Britain abolished slavery across the Commonwealth in 1833, rather perversely, it was slave-owners—and not the slaves themselves, or their descendants—who were compensated for the loss of their ‘property’. The British government paid the contemporary equivalent of £200 billion to the slave-owners. For all this, as Grant describes, propaganda on the islands covered up Britain’s major, two-century role in the slave trade, convincing West Indians instead to focus on a narrative of the Mother Country as an Abolitionist power.

After World War II, there were huge labour shortages in the British health and transport services, as its citizens emigrated to Australia and Canada in large numbers. British officials set up offices in countries such as Jamaica and Barbados to entice West Indians to move to the UK. Many Caribbean nationals thus left their small islands of widespread joblessness in search of a better life and adventure. As Grant notes, ‘West Indians saw Britain as the motherland; they felt awed, privileged and protected by it.’ Poles, Irish and other Europeans also emigrated to Britain at about the same time.

These Caribbean voyages often amounted to improvised journeys without maps, with many immigrants failing to plan carefully what they would be doing in Britain. Some did not even have details of where they would be staying when they arrived. Many had sacrificed enormously to save up the small fortune required to make the trip. Families were often broken up, children were sometimes left behind, and exiles often never saw their parents again, due to the high cost of travel and limited job opportunities in what amounted to apartheid Britain. Many felt powerless and trapped in a cold and unfriendly land: able neither to settle nor to return home. Some were middle-class immigrants with qualifications and skills, but many also came from working class and poor farming backgrounds. Patriarchal Caribbean social structures ensured that many of the early immigrants were men.

The West Indians soon felt the hostility of British society. Within a decade, they were greeted with headlines such as ‘Our Jamaica Problem’, and ‘Racial Troubles in Notting Hill’. Nativist British politicians started talking about controlling the ‘influx’ of West Indians, fanning the flames of anti-immigrant xenophobia. This resulted in Tory politician Peter Griffiths’s notorious ‘If you want a Nigger for a Neighbour, Vote Labour’ campaign of 1964. Many British people saw the immigrants as sub-human, often disparaging them as ‘savages’, ‘monkeys’ and ‘coons’, or as Peter Pan children who never grew up, who were more religious than intelligent. Official government reports described West Indian workers as ‘unsuitable for heavy manual work’ and ‘slow mentally’.

Previous Caribbean notions of a British paradise flowing with milk and honey were very quickly dispelled. Many found conditions worse than those they had left behind, in addition to the cold weather and bad food. They faced open discrimination in employment, housing and accessing loans and mortgages. Many thus held on to low-paying, unskilled, menial jobs as if their lives depended on it. Having been denied employment opportunities in most sectors, the exiles then endured the double indignity of being derided as lazy spongers off the British welfare system. West Indians often lived in damp and cold accommodation with outside public bathrooms, and many were exploited by greedy slumlords. Many were also turned away from housing due to the colour of their skins, with signs openly saying: ‘No Blacks, No Irish, No Dogs’. Black teachers faced threats of their schools being burned down by prejudiced pyromaniacs.

The West Indians in Britain showed resourcefulness in setting up self-help associations and communal funding schemes that helped pay for rent, mortgages and cars. They needed strength of character and nerves of steel to survive the overwhelming hostility and its attendant humiliations that they encountered in their new home. Inspired by African American activist Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955–56, Caribbean citizens staged the Bristol bus boycott in 1963 to end the refusal to hire Black bus-drivers and conductors. The hostile environment also steered many previously quarrelsome West Indians into an overarching sense of Caribbean identity, which helped forge unity among the diverse set of immigrants, but also led to their collectively becoming a secretive community, a set of people leading discreet lives, seeking to stay out of trouble. Exile was a difficult place, occasionally relieved by the kindness of strangers, like an English home-seller, an Irish landlady, or a British solicitor’s helpful firm.

Exile was also a place for the expression of internalised prejudice. The West Indians had no proper sense of their African ancestry, which British indoctrination ensured counted as something of a humiliation. Grant notes, ‘Africa was an embarrassment and a pitiful “dark continent” … Africa was not the motherland; England owned that title.’ British textbooks in the Caribbean reinforced negative stereotypes of Africa, with images, such as of ‘pygmy’ Africans with large bones protruding through their noses, ensuring a sense of backwardness. As Bert Williams, a Jamaican immigrant, notes, ‘We always thought we weren’t Africans; we were better than the Africans and they were actually really slaves.’

The descendants of slaves had thus convinced themselves that they were the masters. In this warped structure of racial hierarchy—a new Black caste system—Africans counted as the untouchable Dalits, and Caribbeans as the noble Brahmins. As Trinidadian émigré Ken noted: ‘I was a white supremacist with a dark skin, a champion of white people against the injustices of the blacks.’ Many middle-class Africans in Britain also held similar negative stereotypes of West Indians. Coming from societies that had been colonised but not enslaved, they often dismissed West Indians as sugar cane-eating, lazy and criminally minded people.

4. Race riots and carnival queens

As in the post-bellum American South, Britain’s white working class feared that West Indians would take away their jobs, despite the latter’s tiny numbers and limited opportunities. There was also, as in America, a widespread fear of Black male sexuality, including among Polish immigrants. These irrational fears erupted into riots in Notting Hill and Nottingham in 1958, and spawned the phenomenon of white ‘Teddy boys’: working-class youth arsonists—armed with knives, iron bars and belts—who moved around in packs attacking West Indians, determined to ‘Keep Britain White’. Many West Indians expressed pride at the courage of Jamaican youths in facing down these white supremacist vandals. In the face of such racist truculence, the British police and government authorities sometimes blamed the violence on the West Indians, and many officials—as well as members of society as a whole—seemed sympathetic to the drunken yobs.

In reaction to the riots, two thoughtful Caribbean leaders decided to counter negative stereotypes—and salvage cultural pride—by fostering a more positive image of their community. Carnivals had been initiated by slaves in the West Indies three centuries earlier; they were now transported back to one of the largest and most culpable slaving nations. Carnivals were an act of nostalgia by homesick West Indians; they unabashedly celebrated Caribbean culture, heritage and arts with marching steel bands, colourful dance troupes and Carnival Queens. In London’s Notting Hill, Trinidadian human rights activist Claudia Jones led the efforts, with the first event held indoors in St Pancras Town Hall in 1959. The £100,000 annual Notting Hill Carnival is now the biggest street festival in Europe, attracting more than 2.5 million people, 40,000 volunteers, and 9,000 police. In Leeds’s Chapeltown, St Kitts and Nevis community activist Arthur France was the moving spirit behind the Carnival in 1967. As his compatriot Carnival Queen of Chapeltown Sheila Howarth noted, ‘people from Caribbean islands were homesick, they were alone and they wanted to find something that was their own. They owned the Carnival …’ The festivals were an act of self-assertion, self-determination and self-empowerment by a community that felt marginalised and maligned in what many had previously—erroneously—thought was their Mother Country.

5. Britain’s 21st century shame: The Windrush scandal

At the beginning of his book, Grant bemoans the ‘reprehensible treatment’ of the Windrush generation by the British government, which deported citizens who had lived in Britain for decades—but he does not really expand on the 2014–2018 scandal. He could have dealt more comprehensively with the traumatic legacy it left, and linked it to the historical experiences of exile, as the scandal seemed to confirm the obsession immigrants had in keeping low profiles, so as to avoid harassment in their adopted home. The book instead ends on the rather over-optimistic note that the descendants of the Windrush generation have moved from the margins to the centre of British society.

A review of the deportation scandal would suggest otherwise. From 2014, the British Home Office—acting like a Dickensian ‘Circumlocution Office’—required that Caribbean arrivals from half a century ago prove that they had not left Britain for two consecutive years, and produce four pieces of documentary evidence for every year that they had resided in Britain. Meanwhile, the mandarins also inexplicably destroyed an archive of old landing slips that could have proved the arrival of many of these migrants. Many West Indians who had travelled as infants on their parents’ passports clearly never had travel documents, as British authorities well knew.

As Home Secretary, Theresa May—buttressed by draconian immigration acts in 2014 and 2016—set out deliberately to create a hostile environment for immigrants. In a reversion to tactics practised by, among others, the Nazis, her administration turned employers, landlords, banks, schools and hospitals into border guards, required to check the papers of immigrants under the threat of hefty fines or even jail terms. A brutal ‘deport first, appeal later’ policy was adopted and, in an action more befitting a banana republic than an established democracy, the government dispatched vans into immigrant areas bearing billboards that read, ‘GO HOME OR FACE ARREST’. May spoke, in xenophobic tones, about ‘citizens of nowhere’. Her policies have had a devastating impact on the lives of more than five thousand law-abiding Caribbean immigrants who have lived in Britain for decades.

As a result of May’s policies, Caribbeans faced Kafkaesque situations in which, overnight, they lost their citizenship, jobs, homes, benefits, pensions and access to public services. Some were jailed, others deported to countries they had never visited. The events ironically coincided with the fiftieth anniversary of racist Conservative politician Enoch Powell’s notorious 1968 ‘rivers of blood’ speech, in which he warned of race wars if immigration to Britain continued. May’s official xenophobia also helped plant the seed that culminated in the Brexit vote, which saw Britain leave the European Union in January of this year. Finally, endemic British racism surely helped power Boris Johnson—who has a long record of making offensive comments about ethnic minorities—to the position of leader, as Prime Minister of the self-defeating Brexit exodus.

The immense contributions of Caribbean citizens to British life—in the arts, politics, literature, food and sport—have rarely been properly recognised, except superficially, for example through annual carnivals. Further, little thought has been given to the huge educational and training investments in the first-generation Windrush émigrés by island governments, who lost their citizens to the efforts to build up post-war Britain’s national health and transport sectors. Intellectuals like Andrea Levy and Stuart Hall; broadcasters like Barbara Blake Hannah and Trevor McDonald; musicians like Eddy Grant, Lady Saw and Patra; film director Steve McQueen; and sports stars like Viv Richards and John Barnes—these all have had a tremendous impact on British life. The islands’ loss was very much the UK’s gain.

While some of the stories in Grant’s rich book of disparate experiences could have been tied more closely together with narrative themes, this is a minor criticism of an important and valuable text that has captured the voices that enriched British society for decades without proper recognition. The author quotes the late Saint Lucian Nobel literature laureate Derek Walcott’s famous ‘Homecoming’ poem, ‘never guessed you’d come to know there are homecomings without home’, to encapsulate the Windrush experience. The West Indian immigrants to Britain discovered that they kept journeying, but somehow never arrived. Never accepted as full citizens, they found themselves permanent exiles in a strange land, and yet still contributed significantly to their adopted home.

- Professor Adekeye Adebajo is the Director of the Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation (IPATC) at the University of Johannesburg in South Africa. He is the author of The Curse of Berlin: Africa After the Cold War (2010); and editor of The Pan-African Pantheon: Prophets, Poets, and Philosophers (2020). He obtained his doctorate from Oxford University and is a columnist for Business Day (South Africa), the Guardian (Nigeria), and the Gleaner (Jamaica).