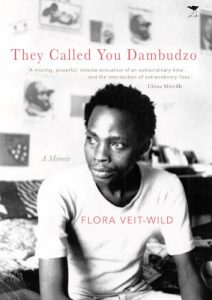

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from They Called You Dambudzo: A Memoir by Flora Veit-Wild.

They Called You Dambudzo: A Memoir

Flora Veit-Wild

Jacana Media, 2021

Publication date in South Africa: March 2021

They Called You Dambudzo was launched on Saturday, 14 November at the InterKontinental bookshop in Berlin:

Flora Veit-Wild with Julius Heinicke

Another launch will take place at the LitFest Harare, which takes place from 25–28 November 2020.

Read an excerpt:

~~~

Harare International Book Fair

August 1983. The first Harare International Book Fair opened its doors at the National Gallery. People flocked to the event. The large hall on the ground floor, where you would on other days find a few forlorn art lovers, was transformed into a multi-coloured maze of bookstalls, posters, cloths and banners. An excited buzz filled the flat-roofed building. Crowds pressed through the alleys between the stalls, admiring everything on display from the publishing houses, booksellers, literary agencies, NGOs, writers’ associations, cultural foundations, literacy campaigns, schools and colleges. They leafed through books, grabbed up pamphlets and catalogues to read through later, asking questions, greeting friends. School classes were paraded through the exhibits, black faces against red or green or blue school blazers, some white faces here and there, black and white teachers urging them on, explaining, pointing to placards and posters.

I was thrilled. I wandered through the maze, drinking it all in. For me, the newcomer to Zimbabwe, it was a great opportunity to get a sense of the country’s book world.

***

The book fair, the first of its kind, three years after Zimbabwe’s independence, was a showcase to the world. After years of isolation under the racist settler regime, the country could boast a flourishing book industry, free education for all, and empowerment through knowledge.

***

The fair was full of success stories. Nobody talked about the faction fighting during that war dividing Mugabe’s ZANU and Joshua Nkomo’s ZAPU and their guerrilla armies ZANLA and ZIPRA. ZAPU was gracefully acknowledged for its ‘complementary role’ in the freedom struggle. Nobody mentioned that Mugabe’s Fifth Brigade, an army unit trained by North Koreans, was killing thousands of people, so-called dissidents suspected of hiding weapons and supporting ZAPU, in Matabeleland. Who knew, as the good-natured crowds strolled around the fair, that at that very moment villagers were being rounded up and subjected to mass beatings? Or marched at gunpoint to public places and executed, after being forced to dig their own graves? Who would have imagined that families were being burned alive in their huts?

Victory, I realised, is seductive. And it is deceptive.

‘I am sorry, ma’am,’ are you registered?’ A young lady at the entrance to the writers’ workshop was holding me up.

‘No, why? Isn’t this free for all?’ Coming from Germany, I would not have imagined that a literature conference could have such restrictions.

‘I am sorry, no, only with prior registration.’

‘But surely the writers should be happy to have a large audience.’

‘There are enough invited guests, I am afraid, and media people. Do you have a press card?’

Trying to suppress my growing irritation, I conjured up all my powers of persuasion. I told the workshop assistant that I had only been in the country for a short while and I did not have a press card yet, but I was writing for a German newspaper. My compatriots would certainly be greatly interested to know how the literary scene in Zimbabwe was flourishing and what such prominent writers as were assembled here had to say.

‘All right, ma’am,’ she conceded finally, ‘I think I can make an exception. Here is a badge. Please wear it when you are moving in and out of the meeting.’

It was a great moment for me. Years later, when I was teaching African literature at Humboldt University, the tableau of illustrious African writers would emerge from my memory, as I saw them lined up at the book fair at that inaugural conference in 1983. I had not yet read many of their works, but I had the great chance to see them live, face to face, and get to know their voices, listen to what they had to say.

The writers were seated at the front of the hall. In the centre I recognised Nadine Gordimer, grande dame and moral conscience of anti-apartheid literature. With her silvery hair and fine-lined white face, she stood out among all the black faces. I always thought there was something of nobility about her, in her demeanour and her way of speaking, soft-toned but distinct, with that typical accent of the white South African educated at English schools. Next to her was her compatriot, Dennis Brutus, the Cape Town poet whose prison poems had stirred the compassion of the world. I would meet this tireless human rights activist, his long grey hair tied into a ponytail, at conferences in later years. He would smile when he saw me and say, ‘Yes, our Dambudzo, nobody like him …’ Lewis Nkosi, another exiled South African, was also there. He was one of Dambudzo’s close friends from London times. A charming womaniser, in time Nkosi would become my own literary mentor.

Ama Ata Aidoo, plump-cheeked, in bright West African attire, was there, having left Ghana and now seeking residence in Zimbabwe. I would get to know her sharp tongue two years later, when I helped organise a writers’ conference on ‘Women and Books’ at the Zimbabwe Book Fair of 1985 and she asked for more money for her participation. ‘How can you let a white woman handle our affairs?’ she complained to the organisers.

Seated next to her was the white-haired Gabriel Okara from Nigeria, looking dignified and withdrawn. ‘Listen to the rhythm of your inner voice,’ was his advice to African writers, as I would learn much later and also teach my students.

Most clearly of all I recall Nuruddin Farah, with his twinkling eyes, the exiled anti-dictatorship author from Somalia, whom I would meet often in later years when I was in the position of hosting readings with him or moderating a discussion at a literature festival. Farah and fellow-writer Taban lo Liyong from Uganda, who was also present at that first book fair, both seemed to regard Dambudzo as their protégé, the angry young man whom they had all met at the famous Horizonte Festival for African writers in West Berlin of 1979. On that occasion Dambudzo had stormed onto the stage, cursing the ‘fascist’ Germans who had not wanted to let him in.

What an illustrious congregation of African literary nobility it was. The event also included writers from francophone countries. Mongo Beti was there from Cameroun. Already in the nineteen-fifties he had been writing about the cruelty of the city and satirising colonial administrators and missionaries. Across language barriers—which did not happen again in later years at such occasions—novelists, poets and playwrights all coming together to celebrate the long-awaited emergence of Zimbabwe from almost a century of colonial and settler rule.

What a privilege, how exciting it was for me, the newcomer, to witness such an eminent moment in Zimbabwe’s literary history. It was a moment of bloom, of a multitude of voices pressing forward, writers back from exile, or from the war, or from their solitary desks where they had been hiding and waiting. The winds of change, which had seen the end of colonial rule in most other African countries two decades before, had finally blown across the country, clearing the sky for the Zimbabwean flag to soar into the blue.

‘Communication Through Literature’ was the theme the organisers had chosen for the Harare convention, which to me seemed to preclude controversy from the outset. This was soon confirmed. A short man with a pompous air about him and serious-looking spectacles chaired the proceedings. He was addressed throughout as ‘Mister Chair’ and he made sure that the deliberations remained as general and non-controversial as the theme suggested. This was Emmanuel Ngara, as I was told, literature professor and current pro-vice-chancellor of the University of Zimbabwe. When I later read some of his essays, I was bored by their dogmatic ideological stance.

***

Much to my relief, I began to realise that I was not the only one in the hall who was getting annoyed at such non-committal, general statements. The bulk of Zimbabwean authors in attendance were seated behind the row of illustrious international writers. I do not recall what they contributed, if at all, but I think Musa Zimunya, the celebrated poet who, shortly afterwards, became the chairman of the Zimbabwe Writers Union (and would become my fiercest adversary) made a statement. He always did. Mungoshi and Nyamfukudza were also there. They did not make statements. They were men of few words.

But there was Dambudzo Marechera.

I saw him excitedly waving his arm from his seat in the back row. Heads turned and the audience shifted on their chairs.

‘What about censorship?’ Dambudzo asked. ‘My novel was banned by the censorship board, just like in the days of Ian Smith! There is no freedom of speech! And what about unemployment? What about drought relief being only delivered into the government-friendly provinces, while the other parts are starving? And that so-called Fifth Brigade, who right now is killing our people in Matabeleland? What about that?’

I found myself smiling. Finally, someone had pointed the finger at the real burning issues. I do not remember whether anyone responded to Dambudzo’s questions but I suspect most of the other writers preferred to keep their mouths shut. The francophone contingency, even if they understood what was going on, retained their stone-like expressions—they were always more formal than anyone else. The chairman, trying to hide his rising irritation but not succeeding, deliberately ignored the constantly raised arm in the back row.

Never easily contained, Dambudzo continued his challenging behaviour throughout the session, jumping up from his seat, heckling those who were speaking, demanding that politicians respond to his questions. He went especially wild when it came to Eddison Zvobgo, minister of Justice and himself a poet, who was chairing an afternoon session. ‘Hey, you, Zvobgo! Comrade Minister! What does your government do to help the ex-combatants?’ he demanded. ‘You are sitting up there in your offices, in your padded chairs and in your villas—look at the cripples lining our streets, out of work, no pay, what do you do to help them?’

As the commotion rose in volume and temperature, Nkosi and Farah walked over to Dambudzo, patting his shoulder, trying to calm him. True to his name, the ‘troublemaker’ was not to be quieted. Even his friends failed. In the end Zvobgo beckoned to his burly bodyguard, who without breaking a sweat manhandled the lightweight out of the room and drove him to a safe distance from the gathering.

Triumphantly Dambudzo later told the press: ‘I have been abducted.’

***

A feature I wrote about the book fair and the writers’ conference was published, again in my ‘home paper’ Nürnberger Nachrichten. It was my first piece on literature in Zimbabwe. Rereading it now, more than 30 years later, I can see how my own political past moulded my take on what was happening in Zimbabwe. My view was different from other European literary critics I met during those first years; I was wary of extolling the nationalist agenda of the day.

‘There is no automatic linkage between revolution and mental and cultural liberation,’ I wrote in a longer version of that first text. ‘The state of literature in Zimbabwe today is still extremely precarious and unsettled. Writers, many of whom have returned from years in exile, have not yet found their position in society.’

I spoke about what government officials were saying to cultural practitioners, how they were warning them to restrain from unwarranted criticism, and I mentioned the gagging order the minister of Home Affairs had issued—under the Emergency Law that was still in force—prohibiting journalists from reporting on what was happening in Matabeleland. By the time I wrote that assessment, in November 1983, I had conducted interviews with several writers.

And I had got involved with Dambudzo Marechera.

~~~

- Flora Veit-Wild is Emerita Professor of African literatures at Humboldt University, Berlin. She lived in Harare/Zimbabwe from 1983 to 1993 and became known for her work on Zimbabwean literature and as literary executor and biographer of Dambudzo Marechera and a founder member of the Zimbabwe Women Writers.

~~~

About the book

‘How shall I tell our story? I hear your voice ringing in mine. I struggle to disentangle a dense tapestry of memories. One thread will be caught up in another. Early images will embrace later ones. My gaze will often be filtered through your eyes, your poems. In the end I will not always be able to tell the original from the reflection. Just as you wrote, Time’s fingers on the piano / play emotion into motion / the dancers in the looking glass never recognise us as their originals.

This book is a memoir with a ‘double heartbeat’. At its centre is the author’s relationship with the late Zimbabwean writer, Dambudzo Marechera, whose award-winning book The House of Hunger marked him as a powerful, disruptive, perhaps prophetic voice in African literature.

Flora Veit-Wild is internationally recognised for her significant contribution to preserving Marechera’s legacy. What is less known about Marechera and Veit-Wild, is that they had an intense, personal and sexual relationship. This memoir explores this: the couple’s first encounter in 1983, amid the euphoria of the newly independent Zimbabwe; the tumultuous months when the homeless writer moved in with his lover and her family; the bouts of creativity once he had his own flat followed by feelings of abandonment; the increasing despair about a love affair that could not stand up against reality and the illness of the writer and his death of HIV related pneumonia in August 1987.

What follows are the struggles Flora went through once Dambudzo had died. On the one hand she became the custodian of his life and work, on the other she had to live with her own HIV infection and the ensuing threats to her health.

What a great article!!! I kept following as the writer introduced all the writers. I hoped I would get to meet Marechera, but my wait was elongated till I thought he would never be mentioned in the story. Then finally, the iconoclastic Marechera that I expected appeared and delivered. I have always asked myself if Marechera ever mentioned Gukurahundi massacres in Matabeleland Provinces; this article answered my question.