By Christa Kuljian and Makhosazana Xaba

Transformation

Who I was

is not who I am.

And who I am

is not who I will be.

Some bits falling off

Other parts sprouting.

Inside of this cocoon

I dream of flight.

—Myesha Jenkins, from Dreams of Flight, Geko Publishing

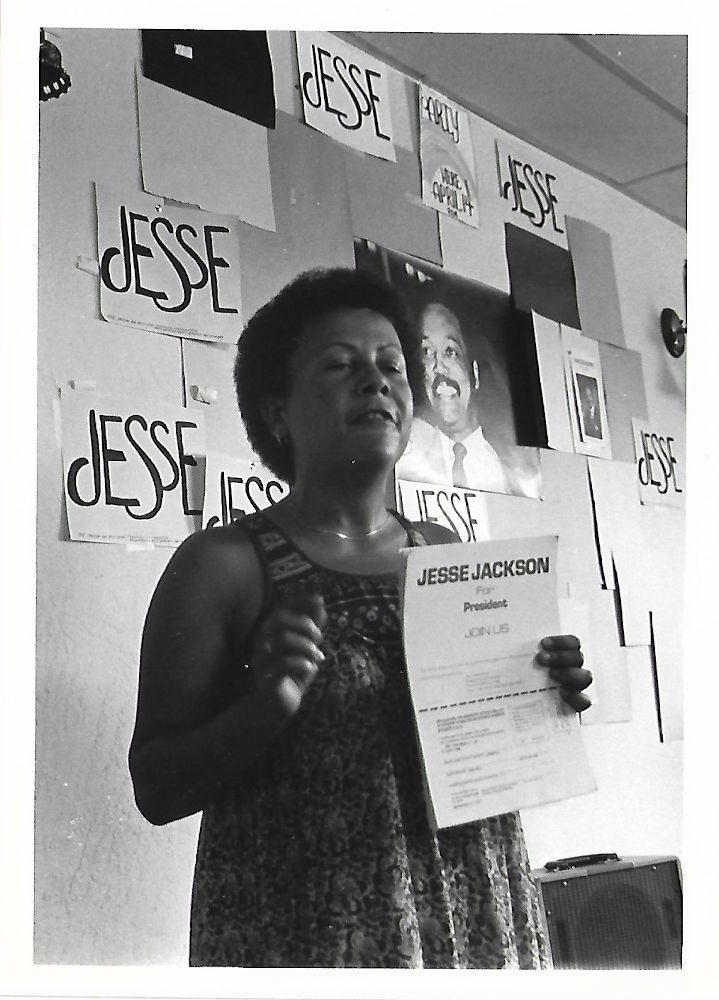

‘Forward ever, backward never’ was the name of Myesha Jenkins’s car in California in the nineteen-eighties. When the car was in drive, it would take her where she needed to go, but put it in reverse and it wouldn’t budge. Kwame Nkrumah used his famous phrase to describe Ghana as it moved away from colonial rule. Myesha used it to christen her car, but it could easily have described her activism as well. Myesha was active with the Third World Women’s Alliance that later transformed into the Alliance Against Women’s Oppression. She worked with international solidarity movements from Nicaragua, Cuba, Ghana, Zimbabwe, Namibia and South Africa.

Myesha was born in 1948 and her parents gave her the name Sharon Rose Moore. She grew up in Altadena, California, and went on her first political march when she was fifteen years old, after members of the Ku Klux Klan in Birmingham, Alabama, killed four young Black girls ‘just like me’ in the 16th Street Baptist Church. Linda Burnham, who was friends and comrades with Myesha for close to fifty years, described her in her twenties as ‘bold, adventurous and very sassy’. In 1967, when Myesha went off to the University of California, Riverside (UCR), there were only seven Black women and two Black men on the campus of four thousand students. Along with another student, Taleb Jenkins, Myesha organised the Black Student Union on the UCR campus and pressured the university for funds to recruit people of colour. According to ‘Jenkins, ‘Myesha was the driving force. We visited most of the high schools in Black neighbourhoods throughout Southern California. It was her idea to create a brochure directed at Black students.’ And by the time Myesha graduated in 1971, there were three hundred Black students at UCR. It was while she was at UCR that she changed her first name to Myesha, the Swahili word for life. And she married Taleb Jenkins, a marriage that lasted ten years.

In her poem ‘Autobiography’, in the Botsotso collection Isis X, Jenkins wrote that she ‘became a communist, studied Marxism Leninism, thought I was a revolutionary, went to meetings, led marches, learned to shoot, organized events.’ The activism and organising that Jenkins began in college flourished in the nineteen-seventies and eighties. ‘The best thing I could do was march,’ recalled Jenkins in a recent interview with Makhosazana Xaba. ‘I had a real good shouting voice. I was the chant leader, but I was also organising.

In an interview with Linda Burnham in 2018, Myesha recalled that she travelled to Africa for the first time in 1974 as the assistant to Ida Strickland with the Third World Fund, a group that raised money for African liberation movements. They travelled to Zimbabwe, Nigeria, Ethiopia, Kenya, Zambia and Tanzania. On behalf of the Alliance Against Women’s Oppression, Myesha attended an ANC women’s conference in London that was chaired by Dulcie September. As a result of that conference, Myesha helped to develop a campaign to release Theresa Ramashamola, a South African political prisoner, and another campaign to raise funds for the Dora Tamana daycare centre in Lusaka, Zambia. In the days before email, cellphones and social media, Myesha organised annual South Africa Women’s Day events in August. She led demonstrations, speaking tours, handed out pamphlets and organised fundraisers.

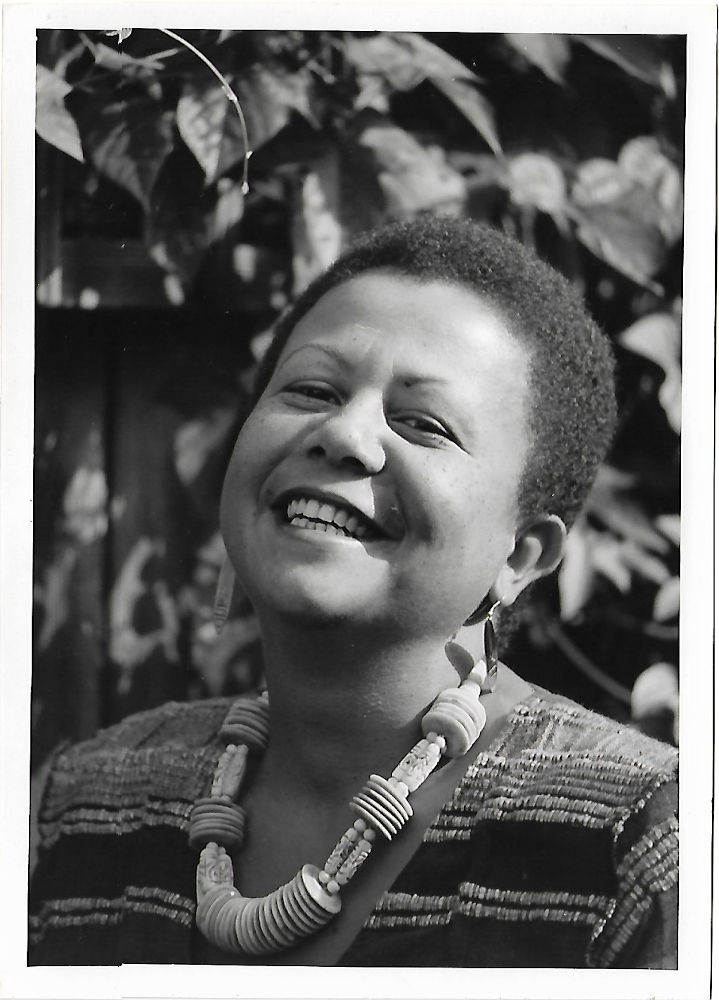

Despite Myesha’s serious work, she was also known for her deep rumbling laugh, her sense of fun and her love of jazz. Describing an event or a conversation, she would often say ‘It was like whoa!’ And her usual greeting was ‘Hi babe’ or ‘Hi hon’. Friends in the United States remember her driving another car she named Ella. The driver’s side window wouldn’t roll up all the way, so she would let her braids blow in the wind out the window.

Endless highway

You can take me for a ride

anytime, day or night

let’s get out of here

ride into the heavens

We’re bumping across the mountains of the moon

passing planets where the oxygen is thin

gliding onto Saturn’s rings

listening to the tinkle of twinkling stars

Yeah, take me for a ride

across galaxies

into another universe

discovering a new sky

surrounded by nothings we’ve known

clear open road

Yeah, take me for a ride.

—From To Breathe into Another Voice: a South African Anthology of Jazz Poetry, Edited by Myesha Jenkins, Real African Publishers, 2017

With Nesbit Crutchfield, Myesha was the Co-chair of the Bay Area Free South Africa Movement (BAFSAM) in San Francisco, California. They organised educational events and protests, and they hosted South Africans including Mosiuoa Lekota, Graeme Bloch, Cheryl Carolus and Chris Hani. Myesha was active with the broader Bay Area Anti-Apartheid Network (BAAAN) as well, which promoted campaigns calling for sanctions and divestment. After Nelson Mandela was released and negotiations began, BAAAN planned to shift its focus. Myesha was conference coordinator for the Strategies for Solidarity conference in May 1992. ‘As South Africa moves into a new phase in its struggle against apartheid, US activists must reassess our role in supporting the democratic process,’ she wrote. Myesha reminded conference-goers ‘we must remember that racism and violence permeate our own society. […] The verdict in the Rodney King case is a harsh reminder of how far we have to go in this country to achieve a democratic and egalitarian society. We must rededicate ourselves to fighting international racism, whether it is in West Oakland or the Western Cape.’ Myesha also coordinated many women’s organisations for an event that welcomed Winnie Mandela when Nelson and Winnie visited the Bay Area in 1990.

Myesha’s day job was with Global Exchange, an organisation working to build people-to-people ties of solidarity for human rights, social and economic justice. She led two delegations to South Africa, one in August 1991 and another in December 1992, that met with ANC representatives, trade unions and community groups. According to her 2018 interview with Burnham, it was on that second trip, after the formal delegation left, that Myesha went to a jazz club and decided she could live in South Africa. When she made this decision, some of her friends and colleagues thought she was crazy and said ‘don’t go’. But by April 1993, she was gone. Myesha fondly remembered that Cheryl Carolus and her husband Graeme Bloch welcomed her on her arrival in South Africa.

Myesha and Christa Kuljian met in Johannesburg in 1993 when they had both recently moved to South Africa. Although Christa is from the East Coast of the US and Myesha was from the West Coast, they had mutual friends in the anti-apartheid movement. ‘While Myesha was working in California, I was working in Senator Edward Kennedy’s office in Washington, DC,’ remembers Christa. ‘Before we knew each other, we were both working on the sanctions and divestment campaign, and the campaign to release political prisoners in South Africa. The Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act in Congress finally passed in 1986.’

By 1996, they were both working on the same floor of Devonshire House in Braamfontein, which was a building filled with NGOs. Myesha was working for Interfund, a consortium of northern donors from Denmark, Norway, Canada and the United Kingdom, and Christa was working for the US-based Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. Both Interfund and the Mott Foundation provided funding and other kinds of support to development NGOs and community based organisations. ‘Both of us were founding members of the Donor Network on Women,’ recalls Christa, ‘that aimed to make sure that donors were engaged in the wide range of efforts to support women and women’s organisations with financial support, capacity building and solidarity.’

According to Charmaine Fortuin, who worked at the Gender Education and Training Network (GETNET) in Cape Town, Myesha was ‘the funder who became a friend, a comrade and sister to so many of her grantees’. She remembers that Myesha’s visits ‘provided the time and space for us to have deep political discussions, to strategise about how and where the funding should be directed to ensure meaningful change in the lives of women … The discussion could start with violence against women over dinner and way past midnight we would be deep into dismantling patriarchy and capitalism.’ Fortuin remembers that Myesha would introduce her Global Exchange delegations—twenty delegations between 2004 and 2010—to many local organisations ‘because she believed that if you wanted to know anything about development work in SA, then grassroots projects and NGOs are where you should go.’ Myesha also worked with South Africa Partners, the South Coast Foundation and the South Africa Sister Community Project.

‘South Africa’s spirit of freedom absorbed me,’ wrote Myesha. She focused on the empowerment of Black women, especially from rural areas. She loved that her job allowed her to meet with community-based organisations across the country and she took long drives in her boxy, red Toyota Corolla that she named Ruby. In addition to Cape Town, she would travel to Tzaneen in Limpopo and Transkei in the Eastern Cape to visit small women’s organisations. She loved the Transkei.

Green

Do you know green?

Tzaneen green?

Transkei green?

Thohoyandou green?

Valley of a Thousand Hills green?

It holds me

breathes calm into me

cleanses me

makes me lush

Do you know

the green

I mean?

—From Breaking the Surface, Timbila Poetry Project, 2005

‘Myesha’s ability to analyse women’s subordination and marginalisation, in spite of our liberal constitution, cannot be overemphasised,’ remembers Nomkhitha Gysman, who worked at Oxfam Great Britain while Myesha was at Interfund. They also worked together in the Donor Network on Women. Gysman later found one of Myesha’s poems, ‘Revolutionary Woman’, to be a useful reference as she worked with women parliamentarians from the Southern African Development Community region.

Revolutionary woman

Don’t admire a revolutionary woman

No one will encourage that

To want to be

A relentless killer woman

A militant organising mother woman

An earth strong rooted woman

An intelligent courageous leader woman

A blood witch warrior woman

An unassuming worker-bee spy woman

No one will encourage that

To want to be

A Dora Maria Tellez, Nora Astorga, Haydee

Santamaria kind of woman

An Asatar Shakur, Nguyen Thi Bihn, Laila

Khaled kind of woman

A Mila Aguilar, Lolita Lebron, Bernadette

Davelin kind of woman

Sheila Weinberg, Cheryl Carolus, Thenjiwe

Mthintso kind of woman

No one will encourage that

Don’t admire a revolutionary woman

Praise her

Love her

Dream of her

Sing for her

Honour her

Emulate her

Don’t admire a revolutionary woman

—Fom Breaking the Surface, Timbila Poetry Project, 2005

Makhosazana Xaba first met Myesha in the mid-nineteen-nineties as well, when she was working at the Women’s Health Project and Interfund was one of their funders. ‘We were advocating for women’s rights over their bodies, sexual rights, sexual pleasure, sexual health, reproductive rights, reproductive health, and rights to information about our health,’ Makhosazana recalls. ‘We were advocating for health policy changes at national level and we conducted research within the health system. Rights to abortion are contested in many countries of the world. We at Women’s Health Project were seen as being too radical by some of our funders. Not by Myesha. She understood what we were about and agreed with us.

‘It was only years later, as poets, that Myesha and I became friends,’ Makhosazana recalls. ‘I learned then that she had also been an activist for women’s sexual and reproductive rights and health in America. We had shared feminist and political values long before we ever met. It took poetry to create the friendship and once we were friends, we shared most of our time together comparing notes on our feminist and political activism. We spent lots of time talking about the ethics, the values and the principles that guided our activism. In no time we realised we knew common people, comrades I knew from my UDF years in South Africa as well as those in the ANC, the ANC Women’s Section and uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) that I knew from my exile years and she had met in the anti-apartheid movement. The connections were mindblowing for both of us. We had been connected through our feminist and anti-apartheid activism long before we met in person. And our passion for women’s rights held our relationship together over the years.’

‘Aunty Myesha was there as my children were growing up in the nineteen-nineties and the two-thousands,’ recalls Christa. ‘We spent many Sunday lunches together with other feminist activists, Lauren Fok, Afsaneh Tabrizi, Natalie Africa, and our families, talking about politics, the country, and the hard work still to be done. We were in the audience at Kippies in May 2003 when Myesha first performed with Feela Sistah!’ The group was Myesha, Ntsiki Mazwai, Napo Masheane and Lebo Mashile. They motivated many a budding poet, inspired many women, and touched many hearts. Feela Sistah! transformed the poetry culture in Gauteng.

Myesha wrote about Feela Sistah! in Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000–2018, edited by Makhosazana and published in 2019. She wrote that she used some of the skills she had learned while she was an activist, and they ‘widely distributed leaflets in popular cafés and venues in Newtown, Melville, on college campuses, and media such as youth radio shows and newspaper event notices’.

One day in late 2004, Myesha and Christa ran into each other by chance at the PostNet in the basement of Killarney Mall. ‘I had left the Mott Foundation and Myesha was moving on from Interfund,’ recalls Christa. ‘Both of us were excited. Myesha was there to print her manuscript, as she was about to publish her first book of poetry, Breaking the Surface, with the Timbila Poetry Project. I was applying to the Masters in Creative Writing at Wits and was there to print out my application.’ Earlier, Myesha had told Christa, ‘You should contact Khosi Xaba. She is just finishing the Wits Masters.’ Christa remembers, ‘Khosi and I had met and she gave me advice about my application and it’s thanks to Myesha that we became friends. Over the years, the three of us talked politics, poetry and writing, and spent many a New Year’s Eve together.’

In November 2008, Christa remembers partying with Myesha and friends after Barack Obama won the US presidential election. ‘She spoke for all of us that night as we expressed hope for the future,’ Christa recalls. The next year Myesha gave her a hand-made book of poems entitled ‘10: For Christa on the occasion of her Birthday’. The closing poem was entitled ‘Yes We Can’. It begins,

Watching him come up from the valley

we elders were at first amused

clinging to the boundaries that defined our lives

It was the children who understood his language

and they took pride in interpreting his words

speaking in a new way

until we could understand

that he asked new questions

as we repeated our same old answers

Yes Change finally came that day

with the challenge to be better than we are

Can you reach out to that vision he asks

Are you in your dreams

If we hold hands we can carry the world

bring kindness to one another

before the first tea break

pull ourselves back from the abyss

and be home for supper

—Unpublished

And then there were those evenings at The Orbit in Braamfontein when Myesha hosted the Tuesday night Out There Sessions of poetry and jazz. Makhosazana and Christa remember celebrating a surprise birthday for Myesha at The Orbit with many friends and a big cake. As Aymeric Péguillan, co-owner and manager of The Orbit, put it, ‘Having Myesha hosting this session was like matching a beautiful hand with the perfectly fitting glove.’ Péguillan remembers how he and the other managers and staff at the Orbit ‘would sometimes stop what we were doing to focus solely on what was being said and shared on stage. Speechless. And Myesha was always there to guide us through these words, and the emotions they triggered.’

Péguillan says that month after month the expectation grew about who would perform at each session. ‘The session was growing and becoming a recognised platform for the art form.’ He began to see ‘more and more regulars’ for the show. ‘Some poets sold books, there were many discussions at breaks, and exchanges between artists and the audience. It became an institution, I think, and certainly one of the best, most enjoyable moments of the month in Orbit.’

In addition to the Out There Sessions at The Orbit, Myesha led many other public poetry-centred initiatives. Poetry in the Air ran throughout the month of August on SAfm for five years. She hosted the monthly Jozi House of Poetry sessions, with Makhosazana, at the Couch and Coffee at the Newtown Cultural Precinct, and later with Phillippa Yaa de Villiers at the POPArt Theatre in Maboneng and the Afrikan Freedom Station in Westdene. After The Orbit closed, Myesha was thrilled to partner with Kaya FM to host monthly live Jazzuary sessions of poetry and jazz at the radio’s studio. Myesha also hosted a weekly programme called Myesha’s Memoirs, when she played jazz and interviewed new poets each week.

When Myesha was in her sixties, and her poetry was flourishing, a friend gave her an old, white Mercedes sedan that she drove for years. After she lost sight in one eye, as a result of an infection, she admitted that she couldn’t always see the curb when she parked, or steer clear of the gate. She named this car Snowy, and was thankful that it took a few knocks and kept her safe.

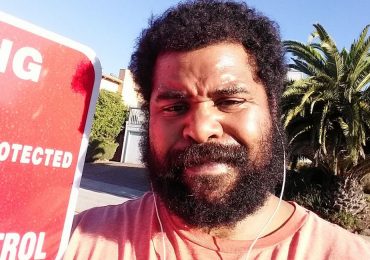

‘Who Myesha was in her seventies was not so different from who she was in her twenties,’ Burnham says. Her basic values included her ‘passion for justice and for truth seeking and truth telling’. She always worked at connecting people and sustaining networks, whether it was in San Francisco in nineteen-eighty or in Johannesburg in twenty-twenty. ‘I am a Black woman and engage with struggles for equality for Black women wherever they may be,’ Myesha said in a 2015 interview with the Daily Vox. ‘I understand colonialism, imperialism, racism, sexism and homophobia as being obstacles to achieving that equality so I stand for women’s rights and Black people’s rights, wherever people are struggling.’ After George Floyd’s murder, Myesha was encouraged to see the #BlackLivesMatter marches across the US. No longer marching and chanting herself, she said ‘Woah! These young people need to take up the baton.’

Myesha’s third collection of poetry, 35 Poems, will be published in 2021 by Lukhanyo Publishers. Myesha approved the cover before she died on 5 September 2020. Kholeka Mabeta at Lukhanyo Publishers and Makhosazana had really hoped that Myesha would have been able to hold the book in her hands, but now they are determined to continue with finalising the manuscript and the production process. ‘It has been a surreal journey,’ says Makhosazana, ‘working on her manuscript after her transition. Comforting and challenging all at once.’

One of the poems that will be included in 35 Poems is ‘Let me Die Dancing’:

A swirling star

lands in my brain

pretending to be

just another thing

until I realize that

the whole universe

is dancing.

Myesha was writing about death as long ago as 2003, when ‘A Plea for Dignity’ was published in a special edition of Timbila: A Journal of Onion Skin Poetry, with the subtitle Nine Black Poets Spit Fire in Grahamstown Arts Festival. Here is an excerpt:

Just call me when it’s time

When I hear your voice,

I will come,

slowly perhaps

but on my own two feet.

‘I am still a revolutionary,’ said Myesha in an interview with Makhosazana earlier this year. ‘I’m using the skills from political organising to build our poetry community.’ Myesha was committed to ‘the idea that we are about change. Our work can change society.’

Acknowledgements: We would like to thank the people who made it possible for us to write this tribute: Natalie Africa, Linda Burnham, Cheryl Carolus, Merle Favis, Charmaine Fortuin, Roma Guy, Nomkhitha Gysman, Taleb Jenkins, Natalia Molebatsi, Aymeric Péguillan, Nolitha Peter, Afsaneh Tabrizi and Nala Xaba and Myesha’s ‘Generals’, Linda Burnham, Phillippa Yaa de Villiers, Lauren Fok, Charmaine Fortuin, Peta Hunter, Christa Kuljian, Napo Masheane, Sharda Naidoo, Gail Smith, Makhosazana Xaba and Nelisiwe Xaba.

- Christa Kuljian is the author of Sanctuary (Jacana, 2013) and Darwin’s Hunch (Jacana, 2016), and is a Research Associate at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WiSER).

- Makhosazana Xaba is a Patron. She is the author, most recently, of the collection of poems The Alkalinity of Bottled Water (Botsotso, 2019) and the editor of Our Words, Our Worlds: Writing on Black South African Women Poets, 2000–2018 (UKZN Press, 2019). She is currently a Research Associate at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WiSER), working towards a biography of Noni Jabavu.