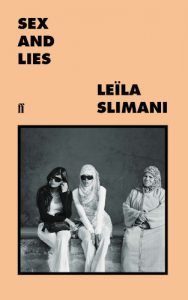

The JRB presents an exclusive excerpt from Leïla Slimani’s new book Sex and Lies.

Sex and Lies

Leïla Slimani (translated by Sophie Lewis)

Faber & Faber, 2020

About the book

Leïla Slimani was in her native Morocco promoting her novel Adèle, about a woman addicted to sex, when she began meeting women who confided the dark secrets of their sexual lives.

In Morocco, adultery, abortion, homosexuality, prostitution and sex outside of marriage are all punishable by law, and women have only two choices: They can be wives or virgins.

In these essays, Slimani gives voice to young women who are grappling with a conservative Arab culture that at once condemns and commodifies sex.

Sex and Lies is an essential confrontation with Morocco’s intimate demons and a vibrant appeal for the universal freedom to be, to love and to desire.

Slimani is the prize-winning and internationally bestselling author of the novels Lullaby and Adèle.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

SORAYA*

‘DON’T FORGET’

It was she who approached me. I was sitting at the bar in a chic hotel in Rabat. She came up to me, laid a hand on the seat next to mine and asked if she could sit there. I said: ‘Yes, of course,’ simultaneously surprised and persuaded by her self-assurance. She sat down, smiling and ready to talk. She began to chat about this and that, apparently anxious not to leave a moment for the embarrassment that could arise between two unacquainted women having a drink together.

She talked about my book, at first. That’s how we’d ended up meeting: thanks to this novel that she had read and wanted me to autograph, after the launch event that had just finished in the hotel’s conference rooms. She had arrived late and been unable to join the discussion. When she’d reached the room, the talk was already over, the books signed, and I had disappeared. A member of staff had been kind enough to let her know I had gone to the bar, where I was enjoying a moment of solitude, a little respite. This was how she’d come to sit down beside me.

*

She must have been in her forties, an attractive woman, though rather unkempt. She hadn’t looked after either her hair or her skin. Her nails were all shapes and lengths and she was smoking like a chimney. But her smile—her wide and infinitely sincere smile—transformed her. She smiled on an impulse of peculiar generosity, and now and then she would laugh, a childlike, naughty laugh. A laugh like crumpling a page that made her look down a little. She avoided all seriousness, seemed not to register pathos at all. At several points, I found her beautiful.

She began, of her own accord, to tell her story. I hardly dared to move. I left my glass where it was, didn’t take a sip, afraid that a single movement might interrupt the flow of her disclosures. She asked me if I have a child. I replied that I do. I haven’t had any. I didn’t manage it. It’s the big regret of my life. She then explained that she had been married very young, to a jealous and controlling man. They had tried for years to have children. She had had many miscarriages, had undergone treatments, then had given up. This failure had put an end to their marriage. And besides, he wasn’t very nice, she said to me, laughing.

She hadn’t been out with any other men before her husband. When I was young, I was very square. I remember, when I was twenty, my college friends were totally wild. They would talk about their lovers, they even told us details of their sex lives. I felt very awkward about all of that. I was a virgin and basically very repressed. After Soraya’s divorce, she had gathered a new group of freethinking, uninhibited girlfriends with whom she could talk about everything. The freedom of their discussions, the licentiousness even, during her afternoons with the girls, had surprised and reassured her. These women explained how to become expert in the art of seducing men, they taught her ways to make them go crazy physically, even going as far as using strange potions.

Things were very different in my family, Soraya confessed to me. Then she described her mother. She was a queen. A strong and beautiful woman, and highly disciplinarian. And her mother had maintained an exclusively close relationship with Soraya’s father. My two sisters and I were hardly allowed to talk to him. As soon as we spotted the opportunity for a moment with him alone, she would call us into the kitchen or somewhere else to help her. She couldn’t stand the idea of his loving anyone other than her.

This adored and feared mother was determined that her daughters be good students, well integrated and sociable. She didn’t stop them attending birthday tea parties or going out in the evenings or even spending the night at a girlfriend’s house. She trusted us, I think. But when she said goodbye, before dropping me off wherever it might be, she always leaned towards me and whispered into my ear: ‘Don’t forget.’ The young woman laughed, her tone at once affectionate and sad.

‘What did she want you not to forget?’ I dared to ask.

‘Don’t forget to stay a virgin.’ That’s what she was telling me. And that awful, sacred, constantly repeated command had become a potent refrain, a voice she could never shake off. I wanted to loosen up this body. After my divorce—which my mother considered a terrible mark of failure—I felt strong, capable of taking my life in hand. I had the strange intuition that my body had much to offer, I wanted to discover pleasure, freedom. I never got there.

She did, however, meet an older man, someone she describes as sensual and patient. They made love often, taking their time. He tried to persuade her to ‘let herself go’. I was trying, she assures me. I was trying with all my heart, but I couldn’t quite do it.

*

For the last few minutes, I’ve had the feeling that she’s prevaricating. That all these stories of hers are powerful and beautiful, but they’re not the heart of the matter. This woman has a secret. I take out a cigarette and offer her one. My lighter is jammed; now the flint’s making my thumb sore. She turns to the man sitting next to us and asks for a light. Like that, she says. That’s how it began. I turned to him and asked him for a light. He lit my cigarette and, as I was sitting alone and so was he, he suggested I join him. He just started talking. He told me his life story as if I were a friend, as if he trusted me implicitly. I was completely transfixed. I was fascinated by this man, to such a degree that it frightened me. I wanted to stay there forever, listening to him, and at the same time I was thinking I should be making for the door right away. He was articulate—and direct.

Flushed, her eyes suddenly haunted, she confesses that at this point her husband—they were not yet divorced—began to call her phone and that, for the first time in her life, she rejected every call and ended up turning her phone off. She and the man talked for hours. She was slightly drunk when, around eleven o’clock, he suggested they go back to his place for a last drink and a kiss. And for all that would follow. She didn’t dare. She took fright and fled, like a mad-woman, without explanation. On the way home, she called a friend and asked him to be her alibi, to pretend they’d spent the evening at the cinema. She memorised the plot of the film they’d shown that evening and then recited it back to her husband word for word. At this she starts to laugh and adds with forced insouciance: I signed my own death warrant. And yet I know it was worth it.

*

* This name has been changed.

~~~

- Leïla Slimani is the first Moroccan woman to win France’s most prestigious literary prize, the Prix Goncourt, which she won for Lullaby. A journalist and frequent commentator on women’s and human rights, she is French president Emmanuel Macron’s personal representative for the promotion of the French language and culture. Born in Rabat, Morocco, in 1981, she lives in Paris with her French husband and their two young children.