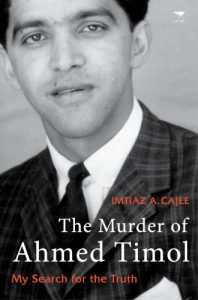

The JRB presents an excerpt from The Murder of Ahmed Timol: My Search for the Truth by Imtiaz A Cajee.

The Murder of Ahmed Timol: My Search for the Truth

Imtiaz A Cajee

Jacana Media, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

I

Shaping my life

I have sketchy, but precious, memories of accompanying Uncle Ahmed to the Roodepoort Club where I would watch him swim. I am told he was an excellent swimmer. I remember also going with him to visit a family friend in Roodepoort, Amina Desai, whom I fondly called ‘Mummy’. She had a white cat. Uncle Ahmed would drive me in Mummy’s yellow Ford Anglia, the same car he was driving when he was detained at a police roadblock on the evening of 22 October 1971.

That evening I was visiting my maternal grandparents’ apartment, No. 2 Choonara Flats, 76 Mare Street in Roodepoort. The adults sat around the kitchen table whispering to each other; suddenly, there was a loud knock on the door and a bunch of burly Afrikaner men entered the flat.

My family regularly made the 180-kilometre journey from their home in Standerton, Mpumalanga to Roodepoort to visit my maternal grandparents. But everything changed when my uncle was arrested. My last recollection of that horrendous evening was of my grandmother, Hawa Timol whom I called Ma, standing at the window while hundreds of people stood outside. My dad had told me that he hoisted me onto his shoulders at my uncle’s funeral a week later, but I have no memory of this.

In May 1976, some five years after my uncle’s death, my grandparents moved to Azaadville, an area west of Johannesburg set aside for people of Indian descent from the towns of Roodepoort, Krugersdorp and Randfontein. My grandfather, Papa Haji Timol, would often take me to the Roodepoort qabrastaan (cemetery) to visit Uncle Ahmed’s grave. Upon our return my grandmother would always ask me, ‘Did you pray for your uncle?’ And I would reply that I had.

Papa loved to hear me recite verses of the Quran and rewarded me with a few cents after each recital. He was a travelling salesman who worked across the entire Transvaal province, as it was then known, with his driver at the wheel of his green Peugeot station wagon. His eyesight was poor and he wore spectacles with thick lenses and he carried a magnifying glass for reading newspapers. Listening to the news on the wireless was a daily routine for Papa. After each individual news report, he would express a ‘sigh’ in acknowledgment. He would consistently rise in the middle of the night to perform the optional Tahujjud prayers and his constant calling and praising of the Almighty in his sleep still echoes in my mind. He was a cool, calm and collected individual with a great temperament—and a walking stick always by his side.

I was in Roodepoort when Uncle Mohammad, Ahmed’s younger brother, was released from police detention on 14 March 1972 after being held in solitary confinement for about 141 days. I remember phoning my father in Standerton from a neighbour’s apartment to tell him the good news. Uncle Mohammad had been denied permission to leave detention to attend his brother’s funeral despite the valiant efforts of the prominent anti-apartheid activist Fatima Meer, who pleaded with Prime Minister B.J. Vorster to intervene.

Uncle Mohammad was detained under Section 10 of the Internal Security Act and was held at the Modderbee Prison in Benoni. He was released after four months without being charged and was immediately served with a five-year house arrest order. His movements were restricted to the magisterial district of Krugersdorp, which included Azaadville. Largely confined to his home, he could only go out on weekdays between 6 am and 7 pm to attend to his job in Johannesburg. If he arrived home a minute after 7 pm, he risked immediate imprisonment. I recall how my grandmother would keep looking anxiously at the clock as 7 pm approached.

He was forbidden from entering his old hometown of Roodepoort where his childhood friends lived and was not allowed to visit his brother’s grave. On Saturdays he was permitted to leave home between 8 am and noon, restricted to the Krugersdorp district, but he still discreetly met other activists at the bird park in Krugersdorp. He had to be in the house from noon on Saturday until Monday morning when he left for work. If a public holiday fell on a Monday he had to remain indoors till Tuesday. He was prohibited from being in the company of more than one person at a time in a public place. This restriction was not always technically possible and was not applied to his attending Friday prayers, or while travelling by kombi with other passengers to and from work, or during his lunch break.

He was also prevented from meeting any other restricted person and was not allowed any visitors at home. However, because he lived with his parents, there were loopholes. I recall regular visits by my mother’s cousins, Iqbal, ‘Baboo’ and his brother, Farouk Dindar, with their families, to the Timol home in Azaadville. Such visits were not without risk as the residence was closely monitored by security police informants. My own family home in Standerton was occasionally visited by Security Branch officers from Middelburg wanting to know the reason for our blue Ford Granada being seen outside the Timol residence in Azaadville on specific dates.

This is how I first realised, from a young age, that there must be people in the community feeding certain information to the police. Who were they, and did they have no conscience? How could they cooperate and support the brutal and oppressive apartheid regime? One of the hardest parts of my investigation into Uncle Ahmed’s murder has been how to deal with unproven allegations that he was possibly betrayed by someone he knew.

In January 1977, there were two weddings in the family, including that of my uncle Ismail, but his brother Uncle Mohammad was denied permission to attend either of the celebrations. He was forced to spend so much time alone. An image I have of Uncle Mohammad, from around that time, is of him sitting in a chair in the front garden with his radio, listening to the BBC, not necessarily to the political broadcasts. He was an ardent Leeds United supporter largely due to the presence of a South African in the team, Albert Johanneson, who was the first black player to play in an FA Cup Final. He was in the team playing against Liverpool in 1965, when Leeds lost 2–1. Johanneson made 200 appearances for Leeds from 1961 to 1969 and a plaque to honour him was unveiled on 11 January 2019, at the Leeds United grounds of Elland Road.

During school holidays, my younger sister Amina and I spent more time than usual in Azaadville and would eagerly await the return from work of our immaculately dressed Uncle Mohammad. One of my mother’s self-imposed routines during these visits was cleaning the cupboards of all the rooms in the house. I remember her finding enlarged pictures of the Bantu Stephen Biko funeral under Uncle Mohammad’s bed. There was also a yellow T-shirt with the image of Biko and his hands in chains.

I was playing in the sun, hitting a tennis ball against the wall on 1 January 1978, when my mother broke the news to me that Ma had called from Azaadville to say that Uncle Mohammad had left. Ma only noticed his absence when he did not come for breakfast. Upon inspecting his room in the back of the main house, she found his bed made up, neat and tidy. I was 11 years old and battled to come to terms with the loss of a second uncle—although this one went into exile and would later come home.

The Citizen newspaper reported on 7 January 1978 9 that mystery surrounded the flight to freedom of the banned chairman of the Johannesburg-based Human Rights Committee, Mohammad Timol. It said relatives had received a call from him from Swaziland. Government officials in Mbabane had expected him to have reported his presence as a political refugee to police or to immigration officials, and then to file an application for political asylum but he had not done so. The truth of his movements would only be determined many years later.

Without him there, the Timol residence in Azaadville was no longer the same during the school holidays. I filled the void with new activities like reading newspaper clippings about Uncle Ahmed and leafing through his photo album. I was overwhelmed to read letters published in newspapers from ordinary white South Africans condemning the actions of the security police and supporting the Timol family. They left an indelible impression on me and made me realise that I could not blame all whites for the heinous murder of my uncle. I began asking my grandmother what happened to this smartly dressed man in tie and jacket, stovepipe pants and cool sunglasses.

Whenever we drove on the highway through Johannesburg on our way from Standerton to Azaadville, we would pass the imposing blue and grey building called John Vorster Square police station. My mother would always remark that this was the place where her brother Ahmed had been thrown from the tenth floor. Silence would always follow her words. I would stare at this monstrous building trying to visualise my uncle falling to his death. As we drove along Main Reef Road, the Roodepoort qabrastaan could be seen in the distance. ‘Pray for your Uncle Ahmed,’ she would say. She would remind me over the years that he would always tell her to keep her heart clean. ‘Allah does not like it when the heart is dirty’, he would say to his sister.

~~~

About the book

27 October 2019 marked the forty-eighth anniversary of the murder of political detainee Ahmed Timol.

‘The passage of twenty-one years [since the TRC] has led me to this Pretoria courtroom, and to the appearance of this giant man who, forty-six years ago, claimed to have been the only eye witness to Uncle Ahmed’s suicide.

‘Joao Rodrigues was the state’s star witness at the 1972 inquest. He would have been deemed pretty perfect for the job of covering up the murder of Uncle Ahmed. A white South African of Portuguese descent, he worked as an administrative clerk at security police headquarters in Pretoria. After more than ten years of service he had ascended just one step up the police hierarchy, to the rank of sergeant—proof, if nothing else, of his loyalty to the cause and for his role in covering up the murder of Uncle Ahmed.’

Follow Ahmed Timol’s nephew, Imtiaz Ahmed Cajee, on his twenty-year journey to find his uncle’s killer and bring him to justice. In 1971, a state inquiry found that Ahmed Timol, held by the security branch of the tenth floor of John Vorster Square, committed suicide by jumping to his death. Forty-six years later, a new inquiry found that Ahmed Timol was murdered.

Only one man remained alive who could tell the truth, a clerk from the police, who was in the room when Timol was pushed. Joao Rodrigues has now been charged with murder and defeating and or obstructing the administration of justice.

The book is a wonderful evocation of a time and places; Johannesburg, London, Mecca, Moscow. The last years of Timol’s life, the woman he loved, and his commitment to a non-racial and free South Africa. His last days are detailed here; the roadblock that was set up to catch him and his treatment by the security police.

Not content with finding his uncle’s murderer, Cajee has been on a quest for justice for other murdered victims of apartheid, whose killers never applied to the TRC and who were never charged, despite the information being available. Cajee investigates the possible deal that was done between the National Party and the ANC during the early nineteen-nineties, and asks how it is possible that so many murderers and torturers were not prosecuted. He is adamant that now is the time to find these people and prosecute them.

In order to commemorate Ahmed Timol’s life, a dedicated website, www.ahmedtimol.co.za, was launched in 2012 to keep memories of his contribution to the anti-apartheid movement alive, and to provide a platform for the further exploration of the unsolved case. The website contains a complete record of just about all the information about Timol’s death, and includes the partial inquest records and the historic findings of the 2017 inquest.