The JRB presents a selection of photographs and personal stories from Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime: South Africa and England, 2008–2016, a new book by the late David Goldblatt.

I wanted to meet people who had done crime or been accused of it and punished. I wanted to meet them not as incarcerated criminals, but paroled or free. I wanted to photograph them not in re-enactment of crime, but in stillness at the scene of crime. And I wanted to record whatever they wished to tell me of their life. And do this not as a journalist or activist, but simply out of a wish to know.

—David Goldblatt

Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime: South Africa and England, 2008–2016

David Goldblatt, texts by Brenda Goldblatt, with an essay by Erwin James

Steidl, 2020

Read the excerpt:

~~~

Sammy Matsebula

I was born in 1968 and was brought up in Nelspruit. Morals and values were respected in my family. My parents are good people. I became a policeman when I left school. My first crime ever was 3 April 1996. My friends convinced me to join them in a plan to hijack a Fidelity Guards cash van. They wanted me to escort them in a police van. We were seven: four policemen, three military. We had somebody inside Fidelity Guards giving us information.

On the day of the heist we went to a shopping mall early afternoon to wait for the cash van. We wanted to do the robbery inside the mall, but the Fidelity Guards were too quick, in and out the mall in a few minutes, so we followed them. The cash van in front, the guys in a car behind it, me at the back in the police van.

As we approached a curve in the road they told me to go ahead and block the cash van. I did that, and the others came out shooting. They had AK-47s, nine millimetres, a rifle. They shot out the wheels and back door. The Fidelity Guards returned fire. Two guards were shot and one died. Our inside man was injured. We took the money and got away. I went to the police station, did my shift and knocked off. I got my share of the money, R75,000. I wanted to go home to Nelspruit and start a business.

We were all arrested that night. Police surrounded my house. They had a helicopter overhead. They hit me in the face. I was bleeding. I had a wife and two beautiful daughters; one was just two weeks old.

We tried to smother the case and bribe the officers, but journalists were involved by then.

We were sent to Pretoria Central prison. We met Colin Chauke there, famous for hijacking cash vans. He and his gang were on trial. They were planning an escape, and invited us to join them. He gave prison guards money to bring in guns, hidden in loaves of bread. Colin and his guys escaped; unfortunately we failed. The same night they took us straight to C-Max, the maximum security prison. It’s like Alcatraz.

The treatment there was terrible. Survival of the fittest. I’ve seen guys killed and raped. I was stabbed, not fighting with anybody but because people hated me for the way I behaved. I didn’t smoke or drink. I was isolated. I didn’t like my co-accused because they were into gangs.

I was sentenced to ninety-six years, reduced to twenty-two because I was a first offender. They confiscated everything in my house that I didn’t have a receipt for. My bank accounts were frozen. I had nothing. When I was in prison I read in the newspaper that my wife and oldest daughter died in a car accident. Police were chasing some gangsters who collided with my wife’s car. When I saw that I collapsed, spent months in a coma. I didn’t know who I was. When I came round I was like a mad person, a living corpse, waiting for my burial. I attended counselling. It was a wake-up call for me. I was sent to Zonderwater Prison. I started going to church, joined a soccer team and became famous, because I was a very good player, a dribbling wizard. I studied music theory and practice, conducted choirs. Did a teaching degree. I was involved in a scandal because I got close to some of the female prison officials and had affairs with them. They transferred me to another prison because of that.

I’m a qualified drug awareness and HIV/Aids Peer Educator, so I facilitated programmes in prison. I enrolled in a theology course and started preaching. I was doing so many positive programmes the Parole Board cut my sentence.

When I came out, my wife was no longer there, my house was no longer there, life was painful. I decided to go back to prison to preach. Now I’m working at Leeuwkop Prison. I show school kids around, warn them against crime. I do get paid but not much.

I’m a gifted person. I’ve got qualifications in theology, music, strategic management and security. I have peer education experience. I play bass guitar, drums, piano. I communicate easily with people. I love working with kids. I’ve sent my CV to different places but I haven’t had any calls.

~~~

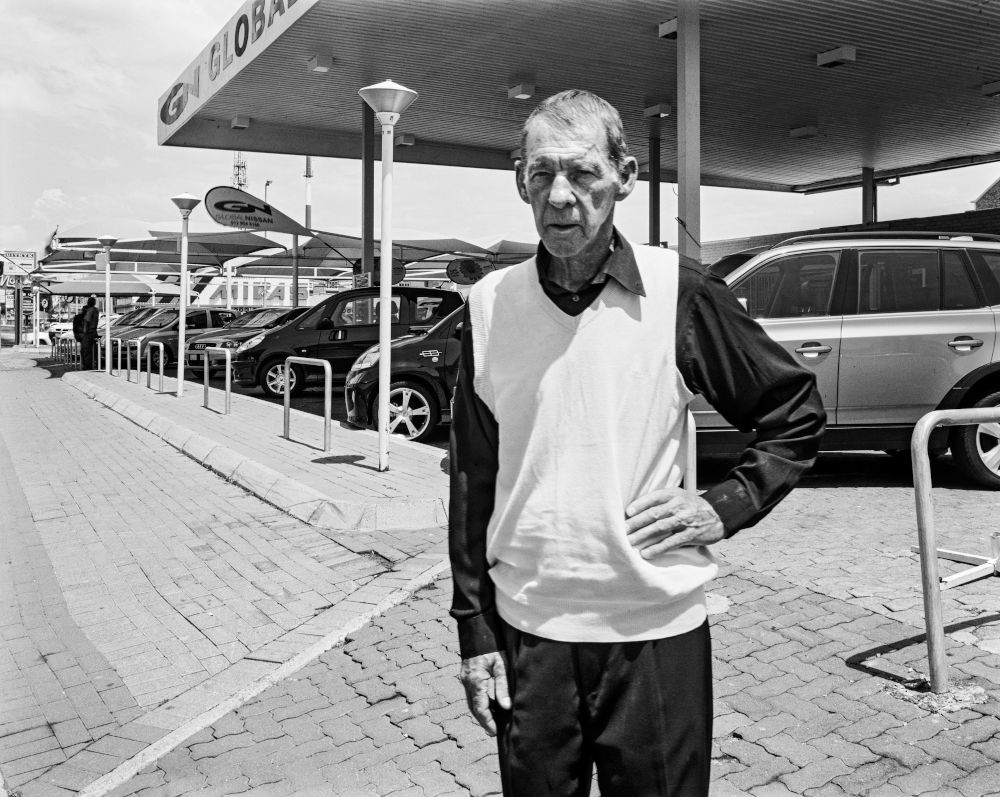

Steve Raykardos

I was born in Johannesburg in 1942. We were a family of ten. My dad was a house painter; we were poor. I swiped whatever I could. I’d go into cafes, get someone to distract the owner, take sweets and run. I never worried about the consequences. I was caught a couple of times, smacked around. I was seven years old.

When I was nine, I walked past a sweet factory and noticed an open window. I went back that evening, climbed in, and passed boxes of sweets to my friends. Next day at school we gave the sweets away. The headmaster brought in the law.

I was sent to a place of safety, Norwood House. I got involved in funny business with crooks, wanting to be a better crook than the next one. When I was thirteen we robbed a shop by climbing through an opening in the roof. We were arrested and sentenced to a caning. They sent me to reform school in Cape Town. I turned eighteen, ran away and stole a car. I was sentenced to four years in jail.

I had a quiet life after my release. Worked as a carpenter, bus driver, builder. I got married and had two kids. Started a pawn shop in Randfontein. I did a good trade and opened a few more shops. I was greedy. Some guys offered me uncut diamonds. I bought them. It was a trap, and I was fined R50,000. I borrowed money for the fine and lost the pawn shops.

I started changing bad cheques in the banks. The police were looking for me so I ran away, left my wife and kids. I discovered that the Jeppe Street Post Office had a broken window in the sorting office. I would climb in every Sunday when there was no staff around. I’d collect ID books and credit cards from personal and company post boxes. I’d put my photo in the ID books, use them to open business accounts at different banks in the names of existing companies. For instance, I would open an account in the name of JS Small Accountants, then I would take all JS Small Accountants cheques from their post box, deposit them in my account. I was making hundreds of thousands of rands.

I got better at it. I would open an account in say, Anglo American Car Sales. Then I’d go to the Anglo American mining company postbag and take all the cheques made out to the company. I would add ‘Car Sales’ to the cheque and deposit it. I was making over R 300,000 a month. I would keep some for expenses and blow the rest at a casino in Swaziland, buy presents for the croupiers. I lost most of the time.

Credit cards were easy. I’d steal them from the post boxes and buy things. They caught me once, bailed me for R300, gave me a suspended sentence. It was OK because I was not using my own name.

Eventually they caught me. I was sentenced to thirty-four years. I escaped. Cut through the prison bars with a hacksaw I managed to buy in prison. Went back to Swaziland and got married. They caught me. My thirty-four years were reduced to nine on appeal. I served seven.

I came out and tried working. Got tired of being broke. I started buying fake IDs and used them to open accounts, forge pay slips, bank statements and drivers’ licenses. With these documents I would borrow money from the bank, buy a car with the cash for a substantial discount and then sell the car in Mozambique or Swaziland. It got big; I was hiring drivers, delivering four or five cars at a time.

I bought a Nissan in Silverton with fake papers. The salesman noticed that my driver’s license wasn’t authentic. He phoned me and asked me to bring the car back because of a problem with the airbags. I was stupid enough to believe him. I was arrested. I owned up to all my crimes, made a plea bargain and received eleven years, reduced to six. I served nearly four.

I was nine when I was taken away from home. I haven’t seen my family for thirty years. I haven’t had contact with my children for ten years. None of my family wants me.

The only scheme I have now is playing the lottery every week. Once a gambler, always a gambler. I would rather die with hope than die not hoping.

~~~

Errol Seboledisho

My name is Errol Seboledisho. I was born in 1979 in Soweto, raised by my parents and grandparents. I finished school in 1996, and then went to technical college to study electrical engineering. My parents died, and my granny took over paying for my education. I left before completing my course, because she had no money.

I made some friends who were into crime. We did housebreaking, pavement robbery, shoplifting. I broke into two different houses when the families were on holiday.

We did pavement robbery in Protea, near Soweto. I’d see a lady coming, and I would go to her, and say, ‘Can you please give me your wallet and your phone so that I won’t hurt you.’ I was asking nicely, because I grew up as a nice person. I used to go to church. I did that six, seven times. Just women. Getting into crime was something I did to make my life better. I used the money to feed my granny and my girlfriend and to buy some clothes for my son.

In 2002, I got caught shoplifting in Protea Gardens Mall. I went to prison and served two-and-a-half years. Now I’m a changed person because of the things that I learnt in prison. I did courses with Khulisa and that helped me. I will never get back into crime.

Sometimes my son comes to me and he asks me for money. If I’ve got it I give it to him. I’ll always encourage him to go to school and never do wrong, never take the property of anybody else. I don’t want him to grow up like me.

I would like to finish my electrical engineer course, to qualify. Sometimes I stand on the street with my CV, try and give it to people. I go to companies and drop it off, apply for jobs where I can. Most of the time they ask, ‘Do you have a criminal record?’ That stigma stops us getting work.

Now I have piece jobs. Sometimes I do gardening. If I see people building at their house in the township I ask for work and maybe I mix cement for them. I am praying very hard so that I can get a job and get on with my life. I want to live my life to the fullest.

~~~

Ellen Pakkies

When I was born we lived on the street. I was two when my mother married. We moved to Kensington, lived in a backyard. The owner’s sons started abusing me when I was four. They came when my parents were drunk. A man lived next to us who had committed murder. One day he told me to lie next to him. I was an obedient child. He raped me. I was sodomised. I was six years old.

I didn’t know what it was to be a child because I grew up without friends, alone. My parents were there, but also they were not there. I didn’t trust anyone. I did not go to school. My mother never saw the pain in me because I kept it to myself, with a smile on my face.

By the time I was eleven I had been abducted twice and sexually abused. I had to share a bed with a rapist because he brought liquor into the house. He began to boss me, so I ran away. I was 13 years old. I was gang raped. I ate out of garbage bins, prostituted myself to stay alive. It felt dirty, but it was my way to escape.

My oldest son was born from rape when I was seventeen. I married when I was eighteen. It lasted six months. My second marriage lasted two years. I had two sons, Abie and Colin, with him. I met Ontil, the man I am married to now, when I was twenty-eight.

Abie was a quiet child, very loving. When he said something he made you laugh. At 13 he began to change, because he started using tik. From then on it was downhill. Clothes and dishes were stolen. Anything he could lay his hands on was stolen. Power lines were cut. Bathroom pipes were stolen. It was so bad we put burglar bars on the doors and windows of our house. They didn’t keep Abie out. One evening I come home, there is no linen on my bed. He stole it through the window with wire. The things that he stole were not important to me. He was important to me. I made this room for him in the backyard. I tried to make him feel that he belonged somewhere, but he never saw it like that.

I had to leave the house quietly because he would follow me, force me to draw money at the ATM, until my wages were finished. I had one pair of panties. I stank because I couldn’t wash properly. One day I thought I could not go on like this. I went to court to get an interdict. It didn’t work. I gave up hope.

One day Ontil and I were going shopping, I let Abie in the house, said: ‘Make something for yourself to eat. Don’t go into our room.’ On the way Ontil remembered he forgot his money at home. I came in to fetch his wallet and saw Abie coming out of our room with two bags full of our stuff. We pursued him, got the bags back. I gave him R20 to buy drugs.

Next morning I went to talk to him. I took him some tea. I saw a rope on the way and grabbed it. I stood in front of him with the rope in my hand. I cried because of what I wanted to do. I put the rope around his neck. He woke with a fright, grabbed a plank and swore at me. I said to him: ’Don’t swear at me and put the plank down, I want to talk to you.’ I asked him: ‘Why don’t you appreciate what I do for you? When are you going to listen?‘ He said: ‘Mammie, I am going to listen’. As he said that I pulled the rope. I cut my hands. I used his sweater to pull tighter.

I went to get dressed and came back to look at him. He was lying peacefully, like someone asleep. I told my boss, Mr Rodgers: ‘I have killed my son.’ He took me to the police station. Mrs Rogers supported me. She bought me underwear and towels. The clothes that I had were full of stains. You must bare your shame before everyone.

My tears continued for a year. I spoke to a psychiatrist during the trial, the first time I told my story. I received a three-year suspended sentence, sixty-two hours community service. Now mothers with children on drugs come to me and I stand by them, help them to the best of my ability. They don’t want to share this with anyone because people look down on them, stepping on their heartache.

~~~

Tiarna Wheeler

Tiarna met her dad for the first time when she was eighteen, at a nightclub. They were both drunk. She hasn’t seen him much since. Her mum is white, her dad is black. Living in a white Bristol neighbourhood, Tiarna suffered racial taunts at school. ‘Once my teacher made me stand in front of the class, told me to go back to where I came from. He said, ‘You don’t belong in this country.’ Next day my mum knocked the teacher out. We moved to Frankley, a mixed neighbourhood. It didn’t help. I was expelled in year eight for dislocating a teacher’s jaw. He ordered me to pick a piece of paper up from the floor. I said, ‘I won’t because you dropped it.’ He said, ‘But that’s what your kind do.’

‘I was bullied. I took a lot of shit from people. I never used to say anything. Once I was rushed by a gang of boys and girls and got badly beaten. I went to my granddad’s house and said, ‘Can you paint my skin white? Because it would be a lot easier.’ He told me to stand up for myself. I took his words too strongly. I went back for all the people who rushed me, got them back. The police kept coming to my mom’s door. It was madness.’

Tiarna’s first court appearance was for beating someone up; she has had nineteen cases in all. ‘I was always the ringleader. My friends didn’t want criminal records, so they always put it on me. The more trouble I got into, the harder my relationship became with my mother. I don’t know what happened at thirteen to make me so angry because my mum said before that I was the best daughter she could ever ask for. She would come down to the police station and sit with me. I think I used to get into trouble because I’d have that time with my mom.’

Tiarna’s first jail sentence was for assaulting Sheila Jones (1). They were feuding over a boy. Tiarna saw Sheila on the bus, attacked her and dragged Sheila by her hair to the bottom of the stairs. ‘I was booting in her face. My cousin pulled me off. He could see I wasn’t stopping. I didn’t know what was going on around me. I saw red.’ The incident was captured on CCTV. At the trial, Sheila insisted on giving evidence behind a screen, claiming to be terrified of Tiarna. Then Tiarna’s mother noticed Sheila laughing as she left the courtroom. Tiarna saw Sheila in town soon after. ‘She’d already been in hospital for three weeks with all the damage I did so I just slapped her up.’

Tiarna served five months of a one year sentence in a young offenders’ institute. ‘I changed for a while but went back to the same group of people and went off the rails.’ Her mother kicked her out and she moved into a hostel. ‘I was drinking, smoking cannabis. I didn’t care about myself or anyone. Didn’t care who I hurt. I went back to prison for breaching my probation order.

‘Things are better now. I am getting on with my mother, I have a boyfriend, I have stopped drinking. I want to marry and have kids, but only when I’ve got a house and a secure job. All my friends have kids and only one is with her baby’s father. I want my child to have everything I didn’t have. Stableness and stuff.’

1. Sheila Jones—not her real name

~~~

Fred Lunn

My mum died when I was five and my brother Terry was two. Our dad was an alcoholic. We starved. He’d leave us for days. I walked the streets scavenging. My brother didn’t learn to walk until he was about three because I could never get him out the cot.

Our dad started living with a woman who had three sons, so we moved to our nan, and lived with her and our aunts and uncles. She proper looked after us. It was stable. We would see my dad once a year. He used to tell us every week, ‘I’m coming on Saturday.’ We’d wait outside from seven in the morning until seven at night for years. When he did turn up all he told us was about gangsters. He wanted us to be like the Kray twins. My nan died when I was thirteen. My family crumbled. The stability evaporated. I was fourteen when I committed my first offence. It was the summer holiday. Our school was a glass building, and we smashed every window we could see.

The family threw me out. I went back to my dad and fought with Don (1), my step-brother. They threw me out too. I lived in a lift shaft, stealing car radios. I’d do two or three cars. Have my money for the day. By sixteen I was running with a group older than me. They introduced me to crack. Suddenly I was in the big time in my head. I started robbing, following this strict criminal code of conduct. You don’t snatch bags, you don’t rob old people, you don’t touch kids, you don’t hit women. It was OK to walk in a bank and stick a gun in a woman’s face because they get insurance. Armed robbery put you on a pedestal. I was flash. I thought, ‘I’ve made it. Now my dad can be proud of me.’ Eventually, I was arrested and convicted. I served over eight and a half years without visits from outside, no letters. Every time I got out for a couple of weeks, I went on the rampage. I was institutionalised. I had status in prison. I had a family.

Once, when I was on compassionate leave from Parkhurst Prison, I tried robbing a bank. Everyone was expecting me to bring drugs back, and I had to keep my status up. I had no way of getting money. I didn’t use my head and rob a bank out of my manor. I went back to one I robbed before. They recognised me. I spent forty-nine days on the run, did a few more robberies. There was no way I was going back to prison empty handed. I’d lose all the respect that I’d gained. I had three weeks left of my sentence. The judge gave me fifteen years. I was twenty-four. The sentence was reduced to eight on appeal. I served it in full.

I got released in February 2000, came to live with my dad. Bad mistake. Don was living there rent-free, treating them like shit, bullying them. He is six foot three and seventeen stone. I never had a mum before, so I started getting on well with his mum. He got jealous, treated me like shit in front of everyone. He didn’t realise how dangerous I was. I got involved in a lot of violence in prison. It was never me but it became me.

One night my girlfriend stayed over with her daughter. Don bullied them. I exploded. Suddenly I had an industrial ball hammer in my hand, went for him. It was an horrific attack. I did a lot of damage. I got life for it. But the judge said, ‘Prison doesn’t work for this guy. Until this man does therapy he will never be released.’

The only place doing therapy was Brendon Underwood. I didn’t want to go because sex offenders went there, but I agreed. Suddenly every other guy was, ‘My name’s so and so and I’m a rapist. My name’s so and so and I’m in for killing kids.’ What I learnt is that I’d been living a complete lie. I’ve wasted my life. I’ve caused all this mayhem. I wasn’t this big gangster, I was a trapped little boy. They kept me there four years even though the judge said two and a half. Obviously I had quite a lot going on.

This therapy prison was a bubble. There was no violence there. After that I went to a normal prison. It took me four years to work my swagger out. It took me two minutes to get it back. You don’t feel it in your heart because now you know it’s all a load of shit. You’ve got to pretend because if you don’t you are eaten alive.

I have been out since September 2007 and it has been a nightmare. Living in hostels, halfway houses. Right now, I am living in a hostel with forty people who are using drugs, drinking. I don’t think that’s productive for me. They are beating me to death with therapy. I’m talked out trying to understand my behaviour. I want to get on with my life and be an adult. At the moment I get, ‘Ooh, he’s wobbled, ooh he had a drink.’ It’s a big shame. I spent eighteen years in prison. I started out not a bad person. I had some bad luck. I made some really bad decisions.

1. Don—not his real name

~~~

About the book

The origins of this book lie in David Goldblatt’s simple observation that many of his fellow South Africans, regardless of their race and class, are the victims of often violent crime. ‘I have asked myself,’ says Goldblatt, ‘not least in the fear and fury of holdups with knives and guns, who are you? Are you monsters? Are you “ordinary” people—if there are such? How did you come to do this? What are your lives?’

And so in 2008 began Ex Offenders at the Scene of Crime, for which Goldblatt photographed criminal offenders and alleged offenders at the place that was probably life-changing for them and their victims: the scene of the crime or arrest. Each portrait is accompanied by the subject’s written story in his or her own words, for many a cathartic experience and the first opportunity to recount events without being judged. To ensure the integrity of his undertaking, Goldblatt paid each of his subjects R800 for permission to photograph and interview them, and any profit from the project will be donated to the rehabilitation of offenders. Ex Offenders also features Goldblatt’s portraits and interviews of subjects in England, made in collaboration with the community arts project Multistory.

Limited edition of 750 books