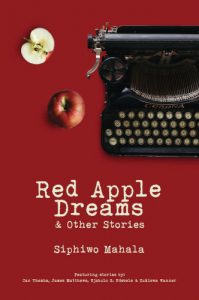

The JRB presents an excerpt from Red Apple Dreams, the new anthology of stories by Siphiwo Mahala.

Mahala is the author of the novel When A Man Cries (2007), which he translated into isiXhosa as Yakhal’ Indoda (2010), and the short story collection African Delights (2011). In January 2016, The Guardian listed African Delights as one of the top ten must-read books in the world. He served as the head of books and publishing at the Department of Arts and Culture for over ten years. His dramatic debut, The House of Truth, based on the life of Can Themba, played to sold-out audiences at the 2016 National Arts Festival in Grahamstown, and at the Market and Soweto theatres in Johannesburg, as well as Sandton’s Theatre on the Square. He earned his PhD with a thesis on the life and work of Can Themba in 2018.

Red Apple Dreams and Other Stories

Siphiwo Mahala

Iconic Productions, 2019

This excerpt is taken from the short story ‘Old Man’s Horse’.

~~~

They heard the commotion caused by the sound of people, horses, dogs and cattle, even before they could see them. Different groups were singing different songs at the same time. Many of the songs were only distantly familiar to Samkelo, as he had not participated in the festival for a long time.

When they arrived at the open veld where the festival was held, there were various groups of people celebrating their own way. A group of men walked rhythmically in a circle, piercing the sky with their sticks as they sang jubilant war cries. Other people were already milling around, friends reuniting, enemies reconciling, witches and witchdoctors, all united by the ecstasy of the moment.

Horses clad in multicoloured costumes pranced around like athletes before a race. They wore decorated saddles, blinkers and adornments around their necks and legs. Tied to the leg-dressings were bottle tops, which made a rhythmic sound with each step.

The girl majorettes were already standing in rank, and behind them was the brass band, comprised of young men with homemade instruments. Samkelo was welcomed warmly by the members of the brass band, many of whom were much younger than him.

The brass band started playing. The rudiments were familiar to Samkelo. They were the same tunes he had played when he was younger. The majorettes marched across the field, with the band following closely behind. The queen of majorettes swung her elaborately decorated stick, displaying sophisticated patterns that were testament to months of rehearsal.

The jockeys were ordered to take their horses to the starting point, and Nomzamo did exactly that. Nyathi, as the custodian of the festivities in the absence of the chief and the regent, objected to her participation. ‘What are you doing here?’ he asked.

‘The same thing everybody else is doing,’ Nomzamo replied nonchalantly.

‘But you are a woman,’ fired the bewildered Nyathi.

‘So what? It is the horse that is gonna be racing, not me.’

‘No, no, no! This is an abomination. We cannot allow a woman to ride with men!’

‘Why? Because they are afraid to be beaten by a woman?’

Their exchange was interrupted by the bellowing of the last horn. Everyone stood in position, ready for the start of the race. Nyathi decided to ignore Nomzamo.

Samkelo raised his arm, then suspended it in the air. He looked around to see if anyone looked like starting before he beat the drum, and also for the sheer joy of suspense. Then he hit the drum with a quick swing. The horses bolted from the starting point, and galloped towards the crowds of spectators. The girl majorettes started scampering in all directions, making way for the racing horses to pass.

The previous year’s winner, Gilindoda, ridden by Mzomtsha, took an early lead, stretching its neck ahead of the others. Nomzamo prodded her horse, and it surged forward, catching up with Gilindoda. They were neck and neck, each determined to prevail over the other. The spectators were ecstatic, cheering, screaming, and jumping up and down. It was a euphoric moment. As they were close to the finish, Saqhwithi edged forward, Gilindoda caught up again, and they crossed the line at the same time. Both Mzomtsha and Nomzamo wore broad smiles on their faces.

There was commotion, some celebrating the dramatic finish, others claiming that one crossed before the other, while others argued that Nomzamo was not supposed to compete with men.

‘Why, because they are a weaker species?’ she asked, and there was no answer.

It was time for celebration. Food and beer were passed around. Friends and foes drank from the same calabash. Older children peeled maize for younger ones. Meat was served to men in big bowls. Boys stood nearby, waiting to be called to come and get generous chunks of meat. Dogs got bones that still had a lot of meat on them, not the usual bare bones.

Samkelo was beside himself with joy. This was what he missed about village life. Now his travel partner had just made him proud. Association with the victor is always something of an honour. He was determined to make his mark too.

When the time for the horse parade came, the horses and their jockeys stood in a file formation, ready to showcase their dance patterns. Samkelo was required to lead the band with his bass drum. He had to hit the drum three times, followed by a horn at intervals, before the band joined in. Samkelo hit the drum the first time, and the horn followed.

After a momentary pause, he hit the drum for the second time, followed by the horn. When he hit it for the third time, a horse appeared on top of the hill before the horn could follow. It pranced on a single spot, stood on its hind legs and neighed while paddling its front legs in the air. Then it galloped down the hill, raising clouds of dust.

‘That’s the old man’s horse!’ shouted Nomzamo.

Men raised their sticks, ready to defend themselves and their children should the horse be aggressive. ‘No, don’t attack!’ shouted Samkelo.

‘Hey wena, this horse has been living in the wild since its owner died!’ shouted Nyathi.

‘It’s not aggressive, I met it twice today. It won’t do any harm.’

When the horse reached them, it pranced once again on the spot, neighed, swished its tail and stood in front of the crowd. Samkelo hit the drum one more time, followed by the final blowing of the horn. Then the old man’s horse led the procession, trotting rhythmically ahead of the rest. Jongikhaya looked majestic without any decorations. The white on his forehead and feet, the long mane; these set the old man’s horse apart from all others.

Nomzamo walked next to her horse, gently pulling it by the reins. She watched over Samkelo, whose biceps were bulging as he frantically beat the drum. Beads of sweat popped on his forehead, and ran down his face and neck. Now his muscles glittered.

The trotting of the horses matched the rhythm of the drum. The young girls shouted, ‘Lahl’ umlenze!’, and the horses, with the old man’s horse in the lead, all kicked to the side at the same time. As they finished the lap around the field, the old man’s horse stood on its hind legs and raised its front hooves in the air, to the delight of the spectators.

After the parade, there was no more singing as the revellers went on feasting.

Samkelo walked over to Nomzamo. ‘Well done. I didn’t know you could compete with men.’

‘I don’t compete with them. I beat them!’ As she said this, she took a glance at Nyathi, who was scurrying away dejectedly. They both burst into laughter.

~~~