In Travellers, Helon Habila delivers a riveting novel that unfolds as a tribute to displaced people and stands as a condemnation of anti-immigration rhetoric and policies everywhere, writes Outlwile Tsipane.

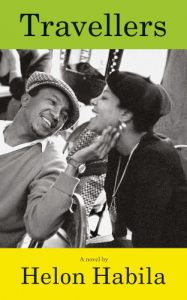

Travellers

Helon Habila

Penguin, 2019

‘Why do white people assume every black person travelling is a refugee?’—Mark, Travellers

A Professor of Creative Writing at George Mason University in the United States, Helon Habila has written three previous novels and a collection of short stories, and edited several anthologies of short fiction. He won the Caine Prize for African Writing in 2001, and his first novel, Waiting for an Angel, won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Book (Africa Region) in 2002.

Habila’s last offering before this, The Chibok Girls: The Boko Haram Kidnappings & Islamic Militancy in Nigeria (2016), is a pocket-sized work of non-fiction that details his findings after a trip to Chibok Town, where the extremist group Boko Haram wreaked havoc in 2014, kidnapping almost three hundred schoolgirls, then burning and destroying everything in its path. Habila’s account is not centred on analysis: rather, we learn of what happened first hand, from girls who evaded kidnapping, some who returned, parents, and people from the community.

In Travellers, Habila continues in this vein, the genre shifting to fiction, and the focus now on migration, and a remarkable and compassionate work is realised. The book is an acute declaration on behalf of unheard voices, steered deftly to achieve an understanding of cause and effect and—perhaps even inadvertently—dismissive of the commonly drawn caricatures that people who cross borders for a better life suffer under.

Travellers, though intense, is unpretentious in how it unfolds. The deep historical and political circumstances that underlie patterns of migration from the global South to the ‘First World’ (and exile) are given expression—deliberately and necessarily—and these form the central themes of the book. In the opening passages, we are introduced to the protagonist, a Nigerian-born academic based in the United States, who remains unnamed throughout, and his wife Gina.

The couple have come to Berlin on the back of a prestigious fellowship awarded to Gina, and the first salvo is fired early: one day, as Gina and her husband, whom I will call Unnamed, are taking a walk through the neighbourhood they have settled in, they are taunted by a child from a nearby school, who waves and shouts ‘Schokolade! Schokolade!’ as they go past. Unnamed turns away, but Gina engages him by waving back. The unsettling scene becomes a constant during their walks, with the boy repeating his cry whenever he sees the couple, soon joined in the charade by his schoolmates. Questions are raised: is Gina insensitive to her husband’s feelings, just oblivious—or is she thinking that children are just being children? The episode indicates that race will be foregrounded in the book, but it lays, too, the first of many probing markers that, because of the potency of Habila’s writing, ensure larger socio-structural questions linger: what will become of these children when they are older? Will they carry this distressing behaviour into their adult lives, albeit systemically?

When Gina receives the news of the year-long fellowship, it comes as a seeming saving grace. She asks her husband to travel with her to Germany; there is the hope the trip may save their marriage. A depressive episode precedes the award, the aftermath of a miscarriage which led Gina to leave their marital home and live with her parents for six months.

At first, her husband is sceptical of the idea, and his worry is captured poignantly in the prophetic lines:

Still I hesitated because I knew every departure is a death, every return a rebirth. Most changes happen unplanned, and they always leave a scar.

Ultimately he agrees, thinking that perhaps the change is what they need: ‘A break from our breaking-apart life’. But circumstances turn out differently for the couple, and as Unnamed unravels he cuts a hapless and forlorn figure, misery being his company.

Travellers also weaves together the stories of people who share an interconnectedness through the similar fate of coming from faraway countries in search of a new place to settle. The book itself takes a nomadic turn, traversing through various cities in Europe. The five chapters that follow the first (which is called ‘One Year in Berlin’) spill out as pieces of reportage by Unnamed. His interviewees, as individuals and at times in cohort, each get to tell their side of the story: the beginning, how it transpired, the current moment, and the as-yet-unknown end. As the novel progresses, they somehow come across one another by chance, enjoying an intrinsic solidarity.

The weight of the book becomes heavier as you read on. The questions flood in. There is nothing of wanderlust in the crossing of borders when you have been uprooted from an environment you’ve always called home, jettisoned from your familial settings. This is what confronts Karim, who once ran a convenience store in Mogadishu, Somalia. When the internal conflict in Somalia began, in the early nineteen-nineties, his father, originally from North Sudan, had built up a sizeable business. But his father died, and the then-teenage Karim took over, managing as best he could for a while, until a brazen local warlord decided to forcefully marry his ten-year-old daughter. Karim’s life was thrown into complete disarray, and together with his family he was forced to leave Somalia. In their quest to find another home, they inevitably ran into further turmoil.

A vital part of Travellers centres on Mark, a young transgender character who grows up in Malawi as Mary Chinomba, a pastor’s child. Mary runs away from home, and eventually makes it to Germany on a scholarship. Having found a place in a new country, and knowing that a return to life in Malawi would be an exercise in futility, Mark writes a letter to his parents informing them of Mary’s death. Mark is a delicately drawn character—so it is especially apposite that it should fall to him to declare, in the novel, that the novel is dead. His utterance is its own repudiation.

(Mark’s story has an unnerving echo in a real-life scam related to me by a Nigerian author based in Canada. Over the past few years, dejected Nigerian youth, she informed me, have found a way to escape the haunting milieu of unemployment by claiming to be gay. Advertisements are placed in newspapers by their parents, publicly disowning their children because of their supposed ‘gay status’. The false renunciations are in turn used to seek asylum in Canada. It becomes a relatively easy task to back up the claims, as there are continuous reports in the media of people being arrested by police on suspicion of being gay. Queerness and migration thus intersect in unexpected ways, but Habila’s sympathetic treatment is, fortunately, the opposite of cynical exploitation.)

As a South African, it is difficult not to feel pangs of guilt when you read Travellers. The notorious xenophobic attacks of 2008 loom large. These attacks, of course, have not stopped, they simply occur on a diffuse scale, throughout the country. Their legacy, meanwhile, includes a structural realignment at the level of government, as police now embark on raids of ‘foreign-owned’ shops in the Johannesburg CBD. The raids have spilled over into the townships, where shops run by Ethiopians, Somalis, Bangladeshis and Pakistanis are looted.

In 2008, some South Africans said ‘Zimbabweans must go’. In 2019, some now say ‘Nigerians must go’. In 1983, when author Taiye Selasi was about four years old, Shehu Shagari, the Nigerian president, said ‘Ghana must go’. It was this pronouncement, of course, that later became the title of Selasi’s first novel. But was Shagari simply returning a sordid favour? After all, it was Ghanaian Prime Minister Kofi Busia who first said Nigerians ought to go, back in 1969. The cycle is vicious.

Our xenophobia has not just been on my mind: ‘Frontières’, a play staged at The Market Theatre in Johannesburg, coincided with my reading of Habila’s novel. It’s tagline: ‘personal stories of refugees in South Africa’. I went to watch it and it added to the helpings of anguish that Travellers was serving me. The play incorporated the precise elements found in the book: it was as if two painters had been given a canvas on which to paint a picture of migration, and the only variance in their depictions was that one was captioned ‘Johannesburg’ at the bottom, and the other ‘Berlin’.

Berlin: the city where Africa was carved up in 1884–5, and now the recipient of that moment’s reverberations. It is in Berlin that Manu, a Libyan doctor whom Unnamed encounters, had promised to meet his wife Basma, in the event they became separated during their treacherous journey across the Mediterrannean. Specifically, they agreed that their meeting place would be Checkpoint Charlie, the famed crossing point between West and East Germany—an obvious symbol of separation and reunification. Manu and Basma’s separation did happen, at sea—and though they both made it miraculously to shore, the events thereafter changed their worlds so radically that it becomes questionable whether true reunion is ever possible.

Books are seldom without their imperfections, and if there is a fault within Travellers it is that it shows explicitly the altruistic efforts undertaken by its author to do justice to the current historical moment. Habila visited Berlin in 2013 on a writing fellowship and met many refugees during his time there, one of whom urged him, ‘You will write about this, no?’ His reply: ‘I’ll try.’

He has tried and succeeded. What historical fiction does is serve as a supplement to history, which is told or untold in inexorably biased ways. Through the didactic elegies in Travellers, we are able to learn and relearn; they become the crucial ground of historical contestation, before history has even had a chance to freeze the happenings of the current moment inside a settled narrative. Travellers is an urgent novel, concerned with the now, and with capturing moments as they happen, and as they’ve happened. It sounds a caution that the unfolding crisis must be contained.

Travellers is haunting in its unambiguous rendering of the precariousness of its characters’ lives. It taunts the reader with its reserve—there are parts that are beguilingly cursory, for effect—and its story is intricate but balanced. Unnamed, the novel’s fulcrum, is a masterfully produced character whose quiescent demeanour does not prevent him from laying bare his own vulnerabilities. What Habila has done, through him, is produce a powerful commentary on displacement, and a stark condemnation of the powers that be.

- Outlwile Tsipane is a literature all-rounder, organising events, facilitating at book festivals and launches, and in management. He has an essay featured in the new book, Black Tax, and he co-writes/runs a football blog called Show Me Your Number. Follow him on Twitter.