Zoë August discusses The Broken River Tent, the rise of the African historical novel, and African literature’s trajectory in general, in a conversation with author Mphuthumi Ntabeni .

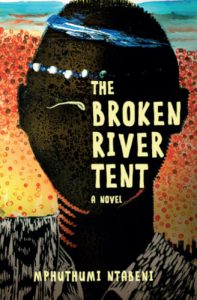

The Broken River Tent

Mphuthumi Ntabeni

BlackBird Books, 2018

Zoë August for The JRB: First of all, what do you consider to be the greatest novel of all time?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Oh, that’s not fair. To be honest, I cannot make up my mind between John Williams’s Stoner and Toni Morrison’s Beloved.

The JRB: So you love American fiction?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: The United States and we have similar political backgrounds, only our demographics are the inverse—minority white oppressing majority black here, and majority white oppressing minority black there. Our literature, quintessentially, is defined by that.

The JRB: What would you describe as the essential qualities of a great novel?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Clarity of writing, especially about philosophical arguments and visceral sentiments. Plain intelligent prose that effortlessly reflects every human shade of thought, doubts, ambiguities, and all. You can see I’ve been memorising my answers [laughs]. Oh, and I appreciate a certain dexterity in narrative language. I like books that pay attention to the use of language.

By the way, by writing in a philosophical sense I mean a casual sense that derives its perspective from human experience—both lived and thought. It must also have some detachment and the application of reason.

The JRB: Meaning?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Books that sing with a unique voice. There’s a lot of talk about poetic writing, or lyrical prose, that makes me a little wary of these terms in our era. But as someone who is interested in my Xhosa tradition of imbongis—griots, if you like—being the stewards of cultural heritage and history, I cannot discount that influence. It is the primary reason that I hold SEK Mqhayi in such high regard. He fulfils that task for Xhosa literature. He stands between our literary cultural foundation and modernity.

The JRB: Are you happy with the direction South African literature is taking?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: It’s not for me to be happy or sad. I follow the trends I like and disregard the rest. I feel we have made missteps along the way by neglecting what’s crucial to our heritage, including our literary one. Musically, for instance, I was happy with the trend Jabu Khanyile and Busi Mhlongo were following. Then they both died young, leaving us confused. It’s as if we were bewitched. For a moment Thandiswa Mazwai seemed to be picking up the baton, then she branched onto a different path I didn’t like. Then came Simphiwe Dana. Well, we’re here and watching.

I could trace a similar path with our literature, beginning with Ntsikana, who laid the foundations for Xhosa music and poetry. It proceeded through the Soga family to the first black intellectuals like Tengo Jabavu, AC Jordan, Walter Rubusana, and so on. Mqhayi was the trove that synthesised all that into a more progressive direction, producing, amazingly, women poets like Nontsizi Mgqwetho. The baton was then picked up by the likes of Noni Jabavu, Tengo’s granddaughter. But then, after the Drum writers’ golden era, our black literary heritage went to exile, and was almost effaced under apartheid. Of course it rose again in the eighties, more political than literary, and began mixing with the preoccupations of white literature in writers like Nadine Gordimer. That’s the thread I seek to follow. Not the kind that edits out the black voices to please the tastes of our pervasive reading public, which is mostly white. I believe finding a narrative voice is one of the most crucial processes of writing. It is learning how to stand alone in your own mind. No one has the right to take that away from you. And for me it is the quintessential definition of authenticity.

The JRB: Do you think there is such a thing as bubblegum literature, as there is bubblegum music?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: I’m afraid so.

The JRB: Can you name examples?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: That’s not for me to say, because literary appreciation is a subjective thing. You get as much as you put in out of it. I know what I don’t enjoy, what to me is as tasteless as a chewed up piece of gum. I am sure you have your own standards also, so let’s just leave it at that.

The JRB: Let me rephrase the question. I’ve heard it said that African novels ramble a lot. That it is difficult to sustain interest when reading them because of this. First, do you accept the definition ‘African literature’—?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: I have my reservations about the term ‘African literature’, but I tolerate it if it comes with a contextual background explaining it as books that are written from within an African Zeitgeist. As for the rambling part, I feel that is mostly bullhorn whining from people who are too used to their hegemony as the yardstick. But let’s try to dignify it with an answer. If brevity forces intellectual and aesthetic distillation, which in turn compels concision, are they saying African novels lack concision? I don’t know. Obviously some do, as is the case with the literature of other continents also. Are they saying you get more of it here? Even if that was the case it’ll still be swinging a blunt axe to generalise, fastening the entirety of African literature with that belt. Yet I can see where the criticism may be coming from. We have great stories to tell but our craft still leaves much to be desired, sometimes. Often we lack what Ernest Hemingway called the ‘built-in, shockproof shit detector’ that’s crucial for getting the words right on the page. We’re still not attentive enough to the use of language, the tools and tricks of strengthening and deepening character, and of refining all these qualities draft after draft after draft and after draft. Writing is very tedious. Good writing also requires top-notch editing. So it is a holistic process that must involve the entire publishing sector, not just writers alone.

The JRB: By Hemingway’s standards, then, where are we getting it wrong?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Look, Hemingway stands at a pivotal moment of Western literary modernism—whose torch he lit, especially with his short stories. I have my reservations about him as a novelist. For me, if you disregard his permanent boyish adolescence, he serves the same purpose Mqhayi does in Xhosa literature, holding a lantern that preserves literary traditions and egging us on to explore the classical world. One of my greatest discoveries was the Homeric tonality in Mqhayi’s poetry. There’s something compelling, a sustaining energy, about telling a story through the deep residual roots of oral literature and tradition. When it’s done right you can feel your heart pump in your throat, as if you were watching the events live, or enacted by a skilled imbongi in a regal court. But you have to read Mqhayi in the original Xhosa language to get this. This is why I’m mostly never satisfied with translations of his poems into English.

The JRB: Would you consider translating them?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Inshallah. In fact, I’ve tentatively started the process informally. His literary voice resonates as aged wood, which is why he provides an excellent platform for us to examine the ‘roots’ of our fractured cultural heritage as Xhosa people.

The JRB: You seem to be very aware of working under the long shadow of Mqhayi.

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: And I wear that as a badge of pride. If I can be so presumptuous, let me draw you into what happened between Homer and Virgil in ancient times. People like Helen Zille mock and degrade us when we claim to be decolonising our minds even while using the weapons of our oppressors, such as the English language. English is a global business language and the lingua franca of many nations, including the Chinese, whose Mandarin is the most spoken language in the world. So it would be stupid of us to cut off our nose to spite our face.

But back to Homer and Virgil. Virgil was keenly aware that, in composing an epic that begins in Troy and ends with the foundations of Rome—describing the wanderings of a great hero—he was working within the Greek literary heritage, thus working in the long shadow of Homer. But he didn’t allow himself to be crushed by the anxiety of that influence, instead he sought and found a way to move it forward. He acknowledged his Greek models while adapting them to Roman themes. Almost everything he did, structurally, in the Aeneid, is a wink at Homer, and so much more. That is how we stand on the shoulders of giants. That is how we make even the English language serve African values. Within no time Latin, which was regarded as rudimentary and crude before Virgil touched it, became the language and lingua franca of an empire, and Greek merely a language of academics.

As Africans we are fresh from the humiliating experiences of colonialism and apartheid. So it is natural for us still to be hiding our vulnerabilities, airbrushing our flaws and quirks. We’ve still not mastered our own authentic literary voice, hence our occasional frustration, because our traditions and culture have been vandalised. Though our anger may be valid it can be destructive if not channelled well, especially through the refining power of tradition. It doesn’t help that, at worst, we’re sometimes treated as ignoramuses, because the norm of universal literature is still regarded as white and Occidental. But we need to be careful not to throw the baby out with the bath water. A place exists in the puzzle of Goethe’s World Literature for Africans to fit in. And the African piece can only be proffered by Africans, no one else. We’re the best of who we are, and the ones we’ve been waiting for. Our Virgils must come from within our midst.

The JRB: Are we sometimes not culpable, though, for how people treat us? I mean why should we require different standards from how the world treats Latin or Asian literature, and so on?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: I don’t think we require different standards and mores. But the African piece of the puzzle is still askew. We can’t square its circle to fit the picture. It must develop organically, and it is. Speeding it up by doing African ‘artificial favours’ doesn’t help either. Where we’re at now is the phase of repairing our historic destiny and identities. In the main this is what informs the recent rise of the African historical novel—Kintu by Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi, House of Stone by Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi—

The JRB: And The Broken River Tent.

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: That too. These are genuine attempts by African writers to leapfrog our literature beyond the twenty-first century. There are different kinds of historical novels: those that dramatise an event from history (what I call minimalist), and those that do the same with a historical epoch (maximalist). Zakes Mda’s The Heart of Redness is minimalist, whereas Little Suns is more maximalist. Fred Khumalo’s Dancing the Death Drill is minimalist, with a cabin mixture of historical curiosities. And so is Niq Mhlongo’s Way Back Home. Then you get the micro-historical studies of social and cultural history, as in Charles van Onselen’s The Seed Is Mine, which blurs the line between fiction and biography but, because of its higher truth ratio, is classified as non-fiction. Triomf by Marlene van Niekerk for me also qualifies as a historical novel, because it depicts an era in our history, though it is not necessarily based on real characters.

In these books African writers are wrestling with their past, trying to find new interpretations and escape the burdens of their histories, and grappling with the historical events that brought us to the status quo. In doing so they are hacking from the historical rock the hues of our identities and figuring out how to fit that into the universal puzzle of global literature. They implicitly recognise that it is the task of the historical novel to sew together the fractured sensibilities of our past.

The advantage of the historical novel is that it places the reader into the historical moment where the fractures occurred, and invites them to listen to the past, as opposed to merely studying it. It trades in the real textures of our past experiences. The truth of the matter is that the ground beneath our feet is still shaking. The past, as William Faulkner insisted, is not even past. It pulls from its origins and pushes forward.

The JRB: History is the tidying up of facts into memory.

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Hence the voice of history has to be composite. We need to filter the din of our past, impose on it patterns that correspond to our authentic idea of ourselves, against competing false narratives. The greatest discovery I made in our historical archives was that there exists a different past from the one handed down by tradition. Of course, as a black person who grew up under apartheid you always suspected that, but it’s another thing altogether to encounter the evidence. You then begin to be suspicious not just of academic interpretations of history, but of the unhealthy silences too.

The JRB: The devolution of effects from causes is always misapplied by the victors, especially in the realm of politics.

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Yes, you expect that from politicians, but not from academics. Events appear sequentially in hindsight. This is the reason I chose the genre of a historical novel, instead of biography, to tell the story of Maqoma. Historians tend to relegate specific events in a sequence, as if they could be fully comprehended as an effect of preceding and a cause of succeeding events. This tends to explain away their political significance, which in turn robs us of learning the true burden of history. Hannah Arendt—I learnt a lot about the philosophy of history from her—makes a crucial distinction between tradition as a burden and the past as a force. Of course she’s an Augustinian scholar, and thus understood that the fracture of tradition usually leads to the dissolution of political and moral values. If the tradition is broken we are either liberated from its burden, or haunted into nostalgia by its absence. The City of God is one of the seminal books that compelled me to think about history as humanity’s journey, from crisis to crisis, towards higher conscience. Hegel might have picked up the idea from Augustine too, which he transmitted to Marx.

If the retrieval of a fragmented past, for us Africans, proves probable for the reconstruction of self or nationhood, it is going to require a great effort of the imagination to make new meaningful beginnings—or refine existing ones—in both thought and action, thus through literature and politics.

The JRB: Outside writers such as JM Coetzee, or the usual ‘white’ literary canon, do we have a strong ‘black’ culture of literary fiction in this country?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Literary fiction is not very popular with black writers, or readers for that matter. In fact, I think this is the reason we get accused of not paying enough attention to language use.

The JRB: Could you define what you mean by literary fiction?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Ow! Novels that don’t rely only on exterior modes of narrative? Are more interested with the interior world of their characters?

The JRB: Stream of consciousness?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Not necessarily, but some form of depiction of a character’s inner life? I don’t know. I mean literature that takes us beyond the gamut of available frameworks of thinking. Something close to what Elena Ferrante means when she says: ‘In literary fiction you have to be sincere to the point where it’s unbearable, where you suffer the emptiness of the pages.’ You know? You can’t explain it but when you read it you know. Whoever, for instance, has read The Days of Abandonment, which is my favourite of Ferrante’s oeuvre, knows exactly what she means. She demonstrated what she means in practice. Very few writers, in their lifetime, achieve the heights of her psychological insight and philosophical clarity. Iris Murdoch came close. The scariest part about Ferrante—scary for those who are in her life—is that she admits that most of her work is autobiographical. She gives a caveat: ‘So what I write is full of references to situations and events that are real and verifiable but reorganised and reinvented as if they had never happened.’

The ideal of literary fiction, for me, because I’m naturally stoic in character, is a novel with a disengaged protagonist, capable of objectifying not only the surrounding world but also her or his own emotions and inclinations, fears and compulsions.

The JRB: That sounds like Phila from The Broken River Tent.

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: [laughs] I guess. I like characters that achieve a kind of distance and self-possession that allows them to act ‘rationally’.

The JRB: What do you mean by that?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: The meaning of rational has obviously changed, relative to the Platonic sense. My favourite philosopher, who’s Canadian and Catholic, Charles Taylor, laments the fact that reason is no longer defined in terms of a vision of order in the cosmos, but rather is defined procedurally, in terms of instrumental efficacy, or maximisation of the value sought, or self-consistency. People now think that by being consistent to their wishful thinking, desires and all, they’re being authentic. No one cares to examine the conscience to see if this is consistent with what’s best for humanity—in other words, if they’re morally upright.

I derailed your question. Anyways. I think literary fiction still scares us as Africans, because in it one relies on the strength of the narrative and nothing much else. We believe in traditional narrative, telling a story with a beginning and an end. With literary fiction you have to coast on the genius, make it up as you go [laughs]. I don’t know much about Afrikaans literature, but judging by how well books like Agaat do I would say they’re well ahead of us in that department. I recently read Patagonia by Maya Fowler, which is also translated from Afrikaans. It is an informative and well written piece of literary fiction based on a real story of Boers in Argentina. I bet you didn’t know there are Afrikaners there? Well, neither did I before I read the book. Then there’s Red Dog, by Willem Anker, which has a special interest to me for being a dramatised life story of Coenraad de Buys, the first white man to settle among amaNgqika. Maqoma, Ngqika’s first-born son and the nemesis of British colonialists during the wars of dispossession, learnt a lot from De Buys, whom they called Khula (Grow—because of his gigantic height), about white people’s mannerisms.

The JRB: Please indulge me by going back to this question: Why did you choose the genre of historical fiction, rather than biography or pure historical narrative, to tell the story of Chief Maqoma? Ah! Jong’umsobomvu! [laughs]

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Because fiction is more trustworthy. It believes in the truth of the past rather than mere facts. It understands that memory is biased and corruptible. Because the novel reports from the battlefront, whereas history is retrospective. Because memory is the doorway to history: I wanted to see things from the intersection of literature and memory. Because emotions and psychological insights are sacrosanct in a novel, whereas historical narratives think these have to be discarded to be objective. I was trying to catch an echo of a memory I never experienced. Because I was within the clairvoyant hallucinatory intensity of cultural transmission. Because I wanted to find a way of arranging and simplifying facts to convey the mental condition of the Xhosa point of view in Frontier-era history. I was seeking a way to make history compulsively readable. To translate the facts of our past and explain the anxieties of our present.

A historical novel distinguishes itself by being loyal to historical facts, and compels the reader to escape into reality. Great historical novels, for me, make historical facts lose their weight and float into the profund. And that opens up history for inspection.

The JRB: There’s the nagging question of the pervasiveness of autofiction in the African novel. To some extent, I think this accusation can be partially made of The Broken River Tent. Is Phila your alter ego? I mean in the way Carla from The Days of Abandonment is to Ferrante?

Mphuthumi Ntabeni: Arguments about the relationship between truth and fiction go back to antiquity. Herodotus deliberately injected his historical narratives with personal and national myths, because he understood that myths sometimes go to the depths of how people understand themselves more than mere facts are able to. Thucydides did away with that in an attempt to be objective and scientific. In doing so he established the foundations for an objective historical narrative even if he, and his progeny, heroically failed. Plato banished poetry and all imaginative literature from his Republic in 380 BC. For him a poet was an imitator thrice removed from the truth, thus had no place in his well-governed city. For me, a historical novelist’s duty is to offer a sense of coherence to historical facts, which include personal history.

I don’t think it is possible for any writer completely to finish a work of imagination without donating a piece of their life experience on it. But this does not mean their work is a mirror of their lives, rather a prism by which they refract their understanding of the world. Fiction, by necessity, glows with a writer’s life, but is also much more than that, it transcends it—good fiction at least. Most of the time when we recount our experiences it is easy to lose a sense of what is true, because memory decays. Making things up is one of the ways we counteract the decaying effects of memory, of closing up the gaps it creates and of reimagining the bias it is burdened with, and is also the best way of shouting against the unhealthy silences of the past. In the end, historical fiction is just an applied history, told from a poetised memory by an informed imagination.

I’d like to give the last words to my mentor, Toni Morrison, talking about her compulsion to reimagine the true story of Margaret Garner in her novel, Beloved:

The historical Margaret Garner is fascinating, but, to a novelist, confining. Too little imaginative space there for my purposes. So I would invent her thoughts, plumb them for a subtext that was historically true in essence, but not strictly factual in order to relate her history to contemporary issues about freedom, responsibility, and women’s ‘place’. The heroine would represent the unapologetic acceptance of shame and terror; assume the consequences of choosing infanticide; claim her own freedom. The terrain, slavery, was formidable and pathless. To invite readers (and myself) into the repellant landscape (hidden, but not completely; deliberately buried, but not forgotten) was to pitch a tent in a cemetery inhabited by highly vocal ghosts […] I wanted the reader to be kidnapped, thrown ruthlessly into an alien environment […]

Something of a similar thought came to me regarding the Frontier era and the life of Chief Maqoma: Ah! Jong’umsobomvu!

This interview is so insightful. Thank you