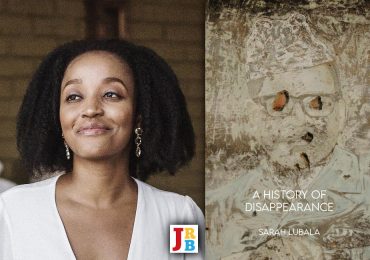

The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec reviews Spring, the third book in Ali Smith’s Seasonal Quartet, a strange beast.

Spring

Ali Smith

Hamish Hamilton, 2019

1.

Smith began her Seasonal Quartet with the aim of returning to the origins of the novel, returning to the word’s original meaning of new, recent, or fresh. She wanted to write four sequential books, each of their time, and have them published in that time. She knew it was technically possible—her previous novel How to Be Both had been produced in a matter of weeks to make its on-shelf deadline—and she wanted to emulate writers like Charles Dickens, who wrote in the moment and released their work instantaneously. But she could not have known that world events would blow up in quite the way they did in the year she decided to begin her undertaking: 2016, the year of Brexit and Trump.

The UK voted to leave the EU in June 2016, just as Smith was finishing the first novel in the series, Autumn. She persuaded her publisher to give her a month’s extension on the book’s deadline to write those events into the story, and it was published in October of that year. And so the first post-Brexit novel begins, with a nod to A Tale of Two Cities:

It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times.

Winter, the second book in the series, was published in November 2017, towards the end of Trump’s first year as president. It begins: ‘God was dead: to begin with.’ A reference to A Christmas Carol this time, appropriate to the season, but this opening was inspired by Google’s search autocomplete, which, when you type ‘God is’ into the search bar, offers as the first suggestion, ‘dead’. And the novel contains numerous references to eerily current political and social happenings—the Women’s March, the largest single-day protest in United States history; Theresa May’s infamous ‘citizens of nowhere’ speech; the moment when Winston Churchill’s grandson barked like a dog at a woman during a UK parliamentary session; the Grenfell Tower fire; Trump’s deranged address to the Boy Scouts of America—which seem to substantiate its first line.

Spring, the latest volume, begins with a slogan for the post-truth era: ‘Now what we don’t want is Facts’. Dickens, once more. The line is an inversion of the opening sentence of Hard Times—‘Now, what I want is Facts’—and the times of Spring are hard indeed.

Reading Smith’s novelistic experiment as it plays out is proving immensely satisfying. There are recurring patterns and clever symmetries. There will be an opening line from Dickens. The book will be loosely based on a Shakespeare play (Smith calls it ‘being under the armpit’ of Shakespeare). There will be an under-recognised artist, who happens to be a woman. Central characters you loved in one book will make delightful, barely tangible cameos in others (there’s a suggestion of Autumn’s wonderful Daniel in Spring, as there was in Winter). There will be puns—although perhaps thankfully these seem to be on the wane in Spring. There will be references to current events so recent they will make you catch your breath. The books are literary double-takes.

One of Spring’s main characters, Brittany, works as a Detainee Custody Officer at an immigrant detention centre (yes, just like those that are dominating headlines this very week). She’s a clever young woman, was one of the top students in her year at school, and had wanted to go to college but her family couldn’t afford it, so she took a job that paid a salary. She has fallen into the habit, picked up from her colleagues, of calling the detainees ‘deets’, and has learned how to ‘talk weather with other DCOs while they’re holding someone in headlock or four of you are sitting on someone to calm him’, although she is careful to keep these cruel flippancies from her mother. Despite genuinely liking some of her gentler workmates, she has started to spend more time with a nastier character: Russell. ‘Russell is a dick. But he’s her friend in here, isn’t he? And you need your friends in here.’

Brittany has also learned:

How to say without thinking much about it, they’re kicking off. We’re not a hotel. If you don’t like it here go home. How dare you ask for a blanket. The day she heard herself say that last one she knew something terrible was happening, but by now the terrible thing, as terrible as a death, felt quite far away, as if not really happening to her, as if happening beyond perspex, like the stuff in the windows in the centre, which weren’t really windows, though they were designed to look like windows.

Brittany is vaguely aware that the job is eating away at her humanity, but she survives by ‘getting on with it’, and by making sure to greet, cheerfully, in her head, the hedges that mark the boundary of the detention centre on her way to and from work, carefully observing their growth as they develop from tiny sprigs into one bushy row.

The novels in Smith’s seasonal quartet are strange beasts. The accelerated pace at which they are composed seems to have loosened up her writing, and stylistically the books are playful and choppy, mixing up font sizes and form. Periodically she will pull you out of the story with a chunk of text that sounds like it is being spoken by a kind of disquieting Greek chorus:

Now don’t go getting us wrong.

We want the best for you. We want to make the world more connected. We want you to feel the world is yours. We want you to see the world through us. We want you to be yourself. We want you to feel a little less alone. We want you to find others just like you. […]

We want to count every step you take. We want to help you be fit and strong. We want to know what makes your heart beat faster. We want you to send us a sample of your DNA and a sum of money so we can help you find out who you are, who your family is and was and where you came from in history, and we want it only for these totally legitimate reasons as a useful service to you. […]

We want the phones we sell to you to work more slowly and less well than the previous models, so that you’ll want to buy a newer model sooner.

We want the black and Latino people who work for us to feel a little less important and protected and able to rise in the company hierarchy than the white people, though we want them to give us their helpful input when it comes to dealing with ethnicity data too. […]

We want you to look at us and as soon as you stop looking at us to feel the need to look at us again. We want you not to associate us with lynch mobs, witchhunts or purges unless they’re your lynch mobs, witchhunts and purges.

We want your pasts and your presents because we want your futures too.

We want all of you.

But as easily as she jolts you out of the narrative world, she effortlessly immerses you right back into it:

It was September Brittany Hall first heard of the girl, the morning when Stel from Welfare went past her in staff lockers and told her, listen, Brit, age of miracles isn’t past, some schoolkid got into the centre and—you won’t believe it. I still can’t. She got management to clean up the toilets.

Management to what? Brit said.

Then she said: how do you mean, she?

All three novels begin with a feeling of strangeness so acute that it is a surprise to discover that there is a story there, and yet there always is. A good one, too. It becomes apparent that the seemingly disconnected stream-of-consciousness interludes are clippings from a journal being kept by one of the characters. And somehow the sometimes chaotic text, while unsettling, is not an annoyance. This is down to nothing less than pure writing skill, and indicates Smith’s authorial mastery.

Smith has found a way to write aesthetically and hopefully about our horrible, hysterical present. She has created a new kind of literary realism. Someone had to do it. After all, as the ‘140 seconds of cutting edge realism’ that opens Part 3 of Spring demonstrates, the realist writing we are faced with at present is generally not a pleasant read:

nex time you are out on a dark night we will get you good and you children you should be scared you imigrant shit you need hate maile to Sort you out you deserve hate you Scrotum face arseole face you are a pedo for fkc sake I cant stand you you are a fukcing Joke you should be force to feed and house a bunch of violence foreign invaders see how you like it fat retard bitch slag slut TRAITOR TRAITER hypocrite your children will Die you are a failure in Life.

2.

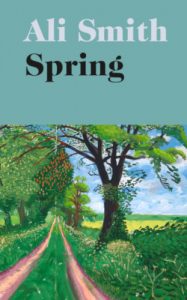

That Smith is one of our most inventive writers of political fiction is becoming clear as the quarter unfolds. But perhaps the most compelling aspect of the series is her writing of people. Like the David Hockney paintings that feature on the books’ covers, Smith’s characters are daubed on the page without elaboration. They are introduced briskly, without detail. And yet somehow they are vital, complex, and utterly real. This realness, however, is not prosaic; it is tempered by unreality, too. In Autumn, there is the mysterious, magnetically imaginative Daniel, whose end-of-life hallucinations give the novel a surreal charge. In Winter, there is Lux, the enigmatic stranger who injects vitality into a miserable Christmas gathering. Most strikingly in Spring this preternatural quality is embodied by Florence, a precocious twelve-year-old mixed-race girl in the mould, perhaps, of Greta Thunberg.

Florence manages to walk right into the labyrinthine detention centre where Brittany works, somehow making it past the innumerable security checks, to confront the centre manager about how the detainees are treated, ultimately shaming him into giving the centre the most thorough clean it’s ever had. The story goes (as the detainee custody officers relay disbelievingly to each other), that she had already walked in and out of four other immigrant detention centres, magically altering the state of mind of a depressed and self-harming detainee in one, and possibly being involved in the unimpeded escape of a woman from another—reportedly her own mother. She is also rumoured to have liberated over a dozen teenage prostitutes from a brothel, while simultaneously making their customers see the error of their ways.

Florence is able to get through turnstiles and onto trains without a ticket, and somehow Brittany finds herself travelling along with her on a mysterious journey one Monday morning, when she should be at work. When they arrive at the station Florence seems to be heading for, they come across a suicidal man laying on the tracks. Florence soothes him, and then seems to hypnotise the menacing station guards, who are determined to arrest him, with nothing more than a friendly look. Smith has intimated that Florence was based on the character of Marina from Shakespeare’s Pericles, the personification of virtue in the face of adversity. On the train, Brittany thinks,

She makes people behave like they should, or like they live in a different better world.

[…]

She’s, what’s the word?

Another old word from history and songs that nobody uses in real life any more.

She is good.

It is suggested Florence’s story doesn’t end happily.

3.

All the novels in the quartet evoke the vital connections and echoes that exist between the old and the new. In one instance in Spring, illustrating the more dismal side of cyclical history, Paddy, a terminally ill scriptwriter, who ranks near the top of the list of characters from books I would like to bring to life, reveals her tragic childhood to Richard, a has-been television film director (‘for my sins’). She grew up in ‘brutal’ Ireland; her father, a labourer, died when she was thirteen, and she and her siblings had to leave school and go out to work. Recalling the conversation after her death, Richard thinks: ‘Thank God those days are over. Thank God it’s better in the world right now.’ The ghost of Paddy responds, ‘Update yourself’:

Kids down the mines right now, she says, right this minute, right this very 13.04. You know there are. They’re mining the cobalt for all the environmentally sound electric cars.

Kids right now in the rags of Hello Kitty clothes sitting in slave labour sheds hitting old dead batteries with hammers to get metals out of them that poison them as soon as they touch them.

[…]

Right now. In these days you’ve just called better in the world.

But these repetitions can also become a light amid the darkness. In a kind of parable that appears three-quarters of the way through the novel, about a young and brilliant maiden who is to be sacrificed as a gift to the gods, to bring life back to the world at the end of winter, Smith manages a subtle yet sharp critique of both ‘cancel culture’—

There are much less bloody ways to hope for spring, the girl said […] than by sacrificing people to them. And anyway, you’re only doing it because some of you get off on the brutality. One or two people always do, always will. And the rest of you are worried that if you don’t do what everybody else is doing then the ones who get off on it might decide to choose you for the next sacrifice.

—and the reductive collectivism of identity politics, as the girl says:

as soon as you all hear me say anything about myself, I’ll stop meaning me. I’ll start meaning you.

A murmur went through the crowd.

My mother told me, they’ll want you to tell them your story, the girl said. My mother said, don’t. You are not anyone’s story.

Despite fairly frequent moments of levity and humour, thematically Spring is the bleakest of Smith’s quartet so far. But perhaps, as Paddy points out, ‘true hope’s actually a matter of the absence of hope’. The fable of the maiden, then, offers some respite from techno-despair: we are not special, things were always like this.

And there are other consolations. The enduring power of art is one. At different points in Spring, we encounter Percy Bysshe Shelley’s poem ‘The Cloud’, read in remembrance of someone and illustrating the unending cycle of life (‘I change, but I cannot die’), and the huge, breathtaking chalk-on-slate images of cloud formations created by the artist Tacita Dean, which:

made space to breathe possible […] After them, the real clouds above London looked different, like they were something you could read as breathing space. This made something happen too to the buildings below them, the traffic, the ways in which the roads intersected, the ways in which people were passing each other in the street, all of it part of a structure that didn’t know it was a structure, but was one all the same.

Elsewhere in the novel, a detainee lying on his back on the floor of his room, staring blankly at the bars and perspex high above his head, informs Brittany, in halting English: ‘I watch clods.’

4.

As an Ali Smith novel, Spring would not have been complete without a demonstration of the magic that can be sparked by coincidence. In the book, Richard is working on a television series about how for a time in 1922 Katherine Mansfield and Rainer Maria Rilke, two extraordinary writers, lived in the same small Swiss hotel, completely unaware of each other, ‘Real people in the same place by chance, and not knowing, not meeting. Passing each other so close. Inches.’ Despite there being no evidence that the two met, and despite Mansfield being close to death from tuberculosis at the time, the producers want to turn the story into a tasteless tale of lust. Paddy, a sparkling autodidact, leaves Richard a note, to be discovered after her death, revealing a more interesting connection, in the form of a letter Rilke wrote while he was still in Switzerland. It’s dated 10 January 1923, the day after Mansfield died:

He is writing to a friend in it about how much he’s been moved by reading some DH Lawrence in German, the novel The Rainbow. He loves it, he says, and reading it has opened a whole new chapter in his life.

Now, I know that Katherine M was good friends with Lawrence and his wife Frieda, and one day she’d confided in them some stories of her own erotic times when she was younger. And something very close to her own stories of her life—I mean close enough to make her very irate when she read it herself—definitely slipped into one of the characters in The Rainbow.

So guess who Rilke finally met? In fictional form, at least.

Spring, as Smith writes, is the season when ‘the coldest and nastiest days of the year can happen’, but also ‘the green in the bulb and the moment of split in the seed, the unfurl of the petal, the dabber of ends of the branches of trees with the green as if green is alight’. It is ‘the great connective’. In its demonstration of the interconnectedness of life through time, its suggestion of hope that art might bring change, its belief in the righteousness of youth, and its playfulness, Spring the novel, like Spring the season, ‘teaches us everything’.

Let’s see what Summer will bring.