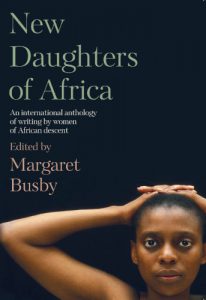

The JRB presents an excerpt from New Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Writing by Women of African Descent, edited by Margaret Busby.

New Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Writing by Women of African Descent

New Daughters of Africa: An International Anthology of Writing by Women of African Descent

Edited by Margaret Busby

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2019

~~~

Esi Edugyan is a Canadian novelist of Ghanaian heritage. She is author of three novels: The Second Life of Samuel Tyne (2004); Half-Blood Blues (2011), which won the Scotiabank Giller Prize, and was a finalist for the Man Booker Prize, the Governor-General’s Literary Award, the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and the Orange Prize; and Washington Black (2018), which also won the Scotiabank Giller Prize, and was shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, and the 2019 Andrew Carnegie Medal for Excellence in Fiction. In 2014, she published her first book of non-fiction, Dreaming of Elsewhere: Observations on Home. She lives in Victoria, British Columbia with her husband and two children.

The Wrong Door: Some Meditations on Solitude and Writing

1.

It is among the most fabled interruptions in literature: after an opium-induced reverie, Samuel Taylor Coleridge regained his senses to discover that an entire poem had written itself within his subconscious. It was one of those stunning and rare visitations—the whole and complete knowledge of a work—and with great urgency he sat at his desk to transcribe what had already been fully expressed within him. He had just written down the fifty-fourth line of the poem when there came a knock at the door: a person, come on business from nearby Porlock. The man would detain him more than an hour; and when Coleridge was finally left alone again, his recollections had completely vanished. He retained only the gist of the poem—a vague assembly of words, a wavering idea—a few scattered lines, the rest, as he put it, ‘passed away like the images on the surface of a stream into which a stone has been cast.’

And so the great ‘Kubla Khan’ was destroyed at the very moment of its making.

Except it probably didn’t happen like that. Coleridge himself was known to embroider and invent—the crucial letter from ‘a friend,’ for instance, that interrupts the eighth chapter of his Biographia Literaria was in fact written by the author himself. In the case of our person from Porlock, some scholars have suggested that Coleridge merely invented him to explain away the fragmentary nature of his great poem. Yet whether a bogey, an unexpected occurrence, or an actual flesh-and-blood man, every writer fears these ‘People from Porlock’—which is to say, we fear the sudden, thought-scattering disruptions that hurt our work. Indeed, these days such disruptions seem the rule. One wants to board up the doors and dim the lights; one wants to drop the blinds, bind the shutters and mount a sign at the entrance saying, ‘The Wrong Door’.

Silence necessarily plays a large role in creation. Privacy is something other than silence, but is its near relative, I believe. Such notions may seem straightforward, at first glance. But in a world where our ideas of self-hood and privacy are ever-shifting, an examination of their role in creation seems valuable.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines silence as ‘the state or condition when nothing is audible; [the] absence of all noise and sound; muteness; taciturnity.’ For the artist, I would add that silence is the state of being deep within oneself; it is the act of cutting out externals so that one may hear the internal. In this way, to greater and lesser degrees, Coleridge’s reverie is how all art gets made. We open a door within ourselves and leave it open, so that the unexpected and the unknown may fill us. I realise this nears the language of the sacred; but that seems fitting, as there is something of the sacrosanct in the act of writing. We take what is percolating and unformed, and through some mysterious process turn the void into utterance. The word ‘lost’ is derived from the Old Norse word ‘los’, which literally means the disbanding of an army. This strikes me as the perfect metaphor for writing. We must break away from those we know, and go away alone, to lose ourselves in the unknown and miraculous.

2.

There is a second kind of solitude—a solitude other than the silence we carve out for ourselves amidst the roar of the greater world. It is needed if an artist is to stand behind his work, even in the face of the fiercest attacks. It is the solitude of certainty.

In a recent essay on silence, the novelist Shirley Hazzard tells a wonderful story that speaks to this necessity. To paraphrase: in 1572, the Renaissance artist Paolo Veronese was called before the Holy Office at Venice to defend himself against charges of blasphemy. He had painted a picture of the Last Supper, and along with the usual figures we expect to see in such a work, he had included random people in the background, dawdlers and loafers, men rambling by. There were people thoughtlessly scratching themselves, people with horrifying deformities, a man staggering with a nosebleed. These images, it was charged, had no place in a sacred painting.

Asked why he would depict such things, the artist replied: ‘I thought these things might happen.’

It hardly seems a viable defense, but as an artistic statement it is enormously resonant. Veronese, in his few words, was arguing for the idea that the principal role of art is to depict the world at hand faithfully, and this includes what is unsavoury and ugly. Anything less than this is hagiography, or caricature.

If it is true that every reader has a favourite book, it is equally true that every book has a favourite reader. We write for everyone and fail to please across the board. And as artists, we must make our peace with the idea that this is alright; that in fact it is a welcome sign that we have challenged people, at least in the comfort of their sensibilities. I thought these things might happen, and so I wrote about them as faithfully as I could. This place of conviction can sometimes be lonely, but the work is all the truer for it.

3.

Privacy is something else again. It is interesting to note that the Chinese word that may come closest to the English word privacy, Si, means selfish. And indeed, there is that quality to it, a turning inward that is necessarily a rejection of others, the uncompromised protection of a sphere of silence from the violating whims of others. In our era of Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, notions of privacy are being shaped and reshaped by the hour, with some arguing that we live in a post-privacy world. The Internet yields all sorts of knowledge we are no better off for knowing.

The German futurist and film critic Christian Heller found himself relinquishing everything to this brave new world: he created a live site in which every quotidian detail of his existence was relayed online. ‘Privacy as a guaranteed personal space free from outside view is shrinking,’ he explained. ‘Long-term privacy will survive only as an exception, as a special case in everyday life.’ It was his belief that our only recourse is to confront the loss of privacy directly. One could read about what he ate that morning, how long it took him to get to work, et cetera. There were even links to his bank accounts, in which all his personal financial data was available for viewing. It was a staggering act of public intimacy, and like all long intimacies, gradually yielded to a wearying sense of banality.

I would argue that, above every other intrusion and interruption, it is a loss of privacy that has the greatest ability to destroy an artist. The knock at the door; the boiled-over kettle; the newborn’s cry—for most (not Coleridge, of course), these interruptions are all surmountable because they are fleeting. They are nothing when compared with the irrevocable loss of a much-needed private sphere of creation.

I think it would come as a surprise to most readers to learn that most writers in their middle to late careers regard with nostalgia their days of obscurity. I remember being puzzled when a writing professor sat us down and told us to savour our collegiate days, because our motives for writing would never again be this pure. We dismissed her as jaded, and longed for the days when we would see our words bound and prominently displayed in the local bookstore.

How frustrated we were by that advice! So much of her meaning seemed to reflect her own anxieties over reviews and prize nominations. But I understand now too that what she was speaking of was a certain lack of privacy, a certain public spotlight that can begin to erode not only our artistic confidence but even motive, the very impetus for writing in the first place. I have spoken to a German writer who after publishing an international bestseller thirteen years ago struggles to write, paralysed by the idea of tarnishing his own reputation with an unlikeable follow-up. I have spoken to an American writer who was so badly shamed for an extra-literary occurrence that she cannot bring herself to enter again the public sphere. All of these tragedies are tragedies of exposure, and they speak to the very fundamental need for an area of silence, a room of, yes, one’s own.

As an extreme example, consider the fate of Elena Ferrante. The pseudonymous author of the Neapolitan novels takes as her subject the friendship between two bright girls in the harsh and limiting world of nineteen-fifties Italy. The novels are brash and intelligent and full of knowing and utterly authentic situations. All of this creativity was taking place under the dome of the most strict obscurity—the only thing the public knew about Ferrante was that she was likely a woman, and even that was unverifiable. In the very few interviews she had given, Ferrante had suggested that her very anonymity was crucial to her artistic process. Only under the cover of a pseudonym did she feel liberated enough to write with honesty. Said Ferrante, via an email interview published in Paris Review in 2015:

Once I knew that the book would make its way in the world without me, once I knew that nothing of the concrete, physical me would ever appear beside the volume—as if the book were a little dog and I were its master—it made me see something new about writing. I felt as though I had released the words from myself.

Then, in the fall of 2016, the dreaded knock came at the door, in the form of a journalist called Claudio Gatti. In an investigative feat that enraged many, he revealed the likely author of the Neapolitan novels to be a Rome-based translator, with some probable input from her novelist husband. Gatti was said to have been blindsided and shocked by the vehemence of the public’s reaction. He claimed he believed he was doing a public good, as Ferrante was slated to release a slim volume of memoirs that fall, which he had now revealed for a lie. Instead, he was castigated and jeered at on social media, cast unrecognisably to himself as the Person from Porlock, a lumbering, unthinking agent of creative destruction.

It is hard to know what to make of this man, Gatti. If he is sincere, then what he failed to understand was that the public had already consented to be lied to long ago. Indeed, the social contract between Ferrante and her readers was such that we accepted her constructed identity with all its attendant untruths. She had never claimed to have been born Elena Ferrante; we did not hold her to the fixity of that identity; we allowed her the fluidity to be what she needed to be. Where, in her relentless silence, we heard a voice—a true, authentic voice—Gatti saw only that last, curious definition of silence, ‘taciturnity’, as if there were some personal spite in her desire to remain out of the public eye. Perhaps the greatest revelation to come out of the controversy was the frightening realisation of how far we have come from our cultural consensus that privacy is a fundamental right.

Given the way of the world now, how do we best find quietude and preserve it? Survival lies, I think, in understanding the varieties of solitude, knowing what is available to us, and what is out of our hands. It is in accepting that the void is sometimes an echo chamber, and knowing it will pass. It is trusting that the silence still exists, out there beyond the spectacle, and that despite the noise the words are still in us, waiting to be made whole.

~~~

About the book

New Daughters of Africa—showcasing the work of more than 200 women writers of African descent, this major international collection celebrates their contributions to literature and international culture.

Twenty-five years ago, Margaret Busby’s groundbreaking anthology Daughters of Africa illuminated the ‘silent, forgotten, underrated voices of black women’ (The Washington Post). Published to international acclaim, it was hailed as ‘an extraordinary body of achievement … a vital document of lost history’ (The Sunday Times).

New Daughters of Africa continues that mission for a new generation, bringing together a selection of overlooked artists of the past with fresh and vibrant voices that have emerged from across the globe in the past two decades, from Antigua to Zimbabwe and Angola to the USA.

Key figures join popular contemporaries in paying tribute to the heritage that unites them. Each of the pieces in this remarkable collection demonstrates an uplifting sense of sisterhood, honours the strong links that endure from generation to generation, and addresses the common obstacles women writers of colour face as they negotiate issues of race, gender and class, and confront vital matters of independence, freedom and oppression.

Custom, tradition, friendships, sisterhood, romance, sexuality, intersectional feminism, the politics of gender, race, and identity—all and more are explored in this glorious collection of work from over 200 writers. New Daughters of Africa spans a wealth of genres—autobiography, memoir, oral history, letters, diaries, short stories, novels, poetry, drama, humour, politics, journalism, essays and speeches—to demonstrate the diversity and remarkable literary achievements of black women who remain under-represented, and whose works continue to be under-rated, in world culture today.

Featuring women across the diaspora, New Daughters of Africa illuminates the richness and cultural history of this original continent and its enduring influence, while reflecting our own lives and issues today.

Bold and insightful, brilliant in its intimacy and universality, this essential volume honours the talents of African daughters and the inspiring legacy that connects them—and all of us.

Contributors include:

Diane Abbott • Yassmin Abdel-Magied • Leila Aboulela • Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀ • Sade Adeniran • Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie • Zoe Adjonyoh • Patience Agbabi • Agnès Agboton • Candace Allen • Lisa Allen-Agostini • Ellah Wakatama Allfrey • Andaiye • Harriet Anena • Joan Anim-Addo • Monica Arac de Nyeko • Yemisi Aribisala • Yolanda Arroyo Pizarro • Amma Asante • Michelle Asantewa • Nana Asma’u • Sefi Atta • Ayesha Harruna Attah • Gabeba Baderoon • Yaba Badoe • Yvonne Bailey-Smith • Doreen Baingana • Ellen Banda-Aaku • Angela Barry • Mildred K Barya • Jackee Budesta Batanda • Simi Bedford • Linda Bellos • Jay Bernard • Marion Bethel • Ama Biney • Jacqueline Bishop • Malorie Blackman • Tanella Boni • Malika Booker • Nana Ekua Brew-Hammond • Beverley Bryan • Akosua Busia • Candice Carty-Williams • Rutendo Chabikwa • Barbara Chase-Riboud • Panashe Chigumadzi • Gabrielle Civil • Maxine Beneba Clarke • Angela Cobbinah • Carolyn Cooper • Juanita Cox • Meta Davis Cumberbatch • Patricia Cumper • Stella Dadzie • Yrsa Daley-Ward • Nana-Ama Danquah • Edwidge Danticat • Nadia Davids • Tjawangwa Dema • Yvonne Denis Rosario • Anni Domingo • Nah Dove • Edwige Renée Dro • Camille T Dungy • Anaïs Duplan • Reni Eddo-Lodge • Aida Edemariam • Esi Edugyan • Summer Edward • Yvvette Edwards • Zena Edwards • Safia Elhillo • Zetta Elliott • Nawal El Saadawi • Diana Evans • Bernardine Evaristo • Eve L Ewing • Deise Faria Nunes • Diana Ferrus • Nikky Finney • Aminatta Forna • Ifeona Fulani • Vangile Gantsho • Roxane Gay • Danielle Legros Georges • Patricia Glinton-Meicholas • Hawa Jande Golakai • Wangui wa Goro • Bonnie Greer • Jane Ulysses Grell • Rachel Eliza Griffiths • Carmen Harris • zakia henderson-brown • Joanne C Hillhouse • Afua Hirsch • Zita Holbourne • Nalo Hopkinson • Rashidah Ismaili • Naomi Jackson • Sandra Jackson-Opoku • Delia Jarrett-Macauley • Margo Jefferson • Barbara Jenkins • Catherine Johnson • Ethel Irene Kabwato • Elizabeth Keckley • Fatimah Kelleher • Donika Kelly • Adrienne Kennedy • Susan Nalugwa Kiguli • Rosamond S King • Donu Kogbara • Lauri Kubuitsile • Goretti Kyomuhendo • Beatrice Lamwaka • Patrice Lawrence • Andrea Levy • Lesley Lokko • Karen Lord • Karen McCarthy Woolf • Ashley Makue • Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi • Reneilwe Malatji • Sarah Ládípọ̀ Manyika • Ros Martin • Lebogang Mashile • Isabella Matambanadzo • NomaVenda Mathiane • Imbolo Mbue • Maaza Mengiste • Arthenia Bates Millican • Bridget Minamore • Nadifa Mohamed • Natalia Molebatsi • Wame Molefhe • Aja Monet • Sisonke Msimang • Blessing Musariri • Glaydah Namukasa • Marie NDiaye • Juliana Makuchi Nfah-Abbenyi • Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ • Ketty Nivyabandi • Elizabeth Nunez • Selina Nwulu • Trifonia Melibea Obono • Nana Oforiatta Ayim • Irenosen Okojie • Nnedi Okorafor • Juliane Okot Bitek • Chinelo Okparanta • Yewande Omotoso • Makena Onjerika • Chibundu Onuzo • Tess Onwueme • Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor • Louisa Adjoa Parker • Djaimilia Pereira de Almeida • Alake Pilgrim • Winsome Pinnock • Hannah Azieb Pool • Olúmìdé Pópóọlá • Claudia Rankine • H Cordelia Ray • Sarah Parker Remond • Florida Ruffin Ridley • Zandria F Robinson • Zuleica Romay Guerra • Andrea Rosario-Gborie • Leone Ross • Josephine St Pierre Ruffin • Minna Salami • Marina Salandy-Brown • Sapphire • Noo Saro-Wiwa • Taiye Selasi • Namwali Serpell • Kadija Sesay • Claire Shepherd • Verene A Shepherd • Warsan Shire • Lola Shoneyin • Dorothea Smartt • Zadie Smith • Adeola Solanke • Celia Sorhaindo • Attillah Springer • Andrea Stuart • SuAndi • Valerie Joan Tagwira • Jennifer Teege • Jean Thévenet • Natasha Trethewey • Novuyo Rosa Tshuma • Hilda J Twongyeirwe • Chika Unigwe • Yvonne Vera • Phillippa Yaa de Villiers • Kit de Waal • Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw • Effie Waller Smith • Rebecca Walker • Ayeta Anne Wangusa • Zukiswa Wanner • Jesmyn Ward • Verna Allette Wilkins • Charlotte Williams • Sue Woodford-Hollick • Makhosazana Xaba • Tiphanie Yanique

About the editor

Margaret Busby OBE, Hon. FRSL (Nana Akua Ackon) is a major cultural figure in Britain and around the world. She was born in Ghana and educated in the UK, graduating from London University. She became Britain’s youngest and first black woman publisher when she co-founded Allison & Busby in the late nineteen-sixties and published notable authors including Buchi Emecheta, Nuruddin Farah, Rosa Guy, CLR James, Michael Moorcock and Jill Murphy. An editor, broadcaster, and literary critic, she has also written drama for BBC radio and the stage. Her radio abridgements and dramatisations encompass work by Henry Louis Gates, Timothy Mo, Walter Mosley, Jean Rhys, Sam Selvon and Wole Soyinka, among others. She has judged numerous national and international literary competitions, and served on the boards of such organisations as the Royal Literary Fund, Wasafiri magazine and the Africa Centre. A long-time campaigner for diversity in publishing, she is the recipient of many awards, including the Bocas Henry Swanzy Award in 2015 and the Benson Medal from the Royal Society of Literature in 2017. She lives in London.

How’s it going, joburgreview?

Don’t you wish you were Instagram cool?

Well, today I will teach you something that will improve the way you Instagram.

Imagine: It’s Friday morning and you’ve promised yourself you’d hit the gym today.

You pull out your phone.

Make your way to Instagram.

Youare flabbergastered at what is waiting for you: Over 832 likes on one of your pictures! There, you see a a huge amount of likes on your pictures–over 832 on a single photo alone.

You rise out of the warmth of your bed, and head to the kitchen. You want a drink, so you put the kettle on for some tea, and check Instagram again.

Bam! Another 63 likes.

Ding—another message pops into your inbox from a follower. They are asking you for advice on how you manage your food, and are congratulating you on your third month of hitting the gym.

A grin makes its way on your face as you see another message. This person emailed you to let you know she loves your posts.

Within minutes, your cell buzzes AGAIN.

Wow, ANOTHER message. You close your phone and throw it in the bag. Time for the gym.

Listen, joburgreview, most people just are not in control of their life. Heck, they can’t even get themselves to have a balanced brekky, much less hit the gym.

I’m here to show you how to take the reigns of your Instagram.

Now, what if you could raise your engagement by 100%, or 1000%?

It’s not complicated to do, although almost no one does. Just visit our website. There, you’ll learn how to garner Instagram likes and followers like mad…easily.

In just minutes after posting, you have your images piled with likes.

With this you have a big chance to be featured in the “Top Post” section.

And because we love you, we made testing things out as simple as kitchen-cooled apple crumble:

1. Click https://rhymbo.pro

2. Enter in your Instagram username.

3. 10 – 15 likes are going to be sent to your three most recent pictures. Just like that.

Being a everyday name on that page will supercharge your growth 10x, easy. But if you want the fame, you’ve got to reach for it. Are you ready?

See you on the flipside.