Lebohang Mojapelo reviews Ngũgĩ: Reflections on His Life of Writing, a collection of essays that reflects on the life and work of Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, who celebrated his eightieth birthday in 2018.

Aririrititiii……………………………………!

Hurray to the author of three score books and more!

Salute to the de-colonizer of the mind, language and culture!

High fives, to the advocate of African and global indigenous languages!

Pongezi to the recipient of a score plus international honorary degrees!

Hongera to the annual winner of many Nobel Prizes of the heart!

Shangwe na vigelegele for a beloved Kenyan and African of the soil!

Embraces to a champion of human rights and citizen of the world!

Five ngemi for Ngũgĩ, child of Wanjiku:, Ngũgĩ, son of Thiong’o!

Ululation for the ‘beauty-full’ one who was born four score years ago!

Ashe! Afya! Moyo!‘

—Micere Githae Mugo

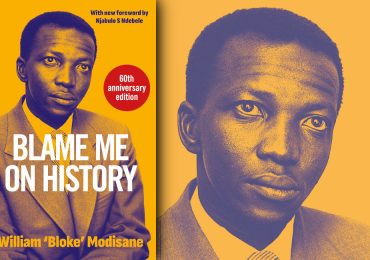

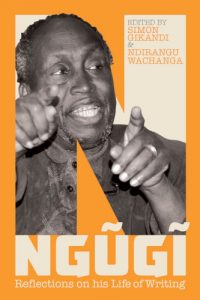

Ngũgĩ: Reflections on His Life of Writing

Ngũgĩ: Reflections on His Life of Writing

Edited by Simon Gikandi and Ndirangu Wachanga

James Currey, 2018

It is a truth universally acknowledged, that an African in possession of a curiosity about literature has read a book by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and that it probably changed the direction of their life and their perspective on their African identity. Ngũgĩ: Reflections on His Life of Writing is a book dedicated to the indelible Ngũgĩ—his writing, his thinking. It covers a range of his work, from his first novel, Weep Not, Child, published in 1964, to his play Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), a seminal work first performed in 1977 and co-written with Ngũgĩ wa Mĩriĩ and the peasants of rural Limuru; from his Marxist-influenced fiction Petals of Blood (1977) and Devil On the Cross (1980) to his philosophical musings, the most noted of which is undoubtedly Decolonising the Mind (1986). The many considerations of Ngũgĩ’s work compiled here have produced a remarkable book, one which demonstrates the vastness of his influence, hailing him alternately as a writer, political prisoner, groundbreaking playwright and father. The contributors range from former students, to colleagues, to those who met him by chance and those who held him close when he was in exile. Fortunately, their collective effusiveness does not descend into the saccharine, but instead holds Ngũgĩ with dignity and delicacy, honouring what can only be described as his heroism.

Images and snippets of Ngũgĩ flitter through my childhood. I remember flipping through a copy of The Trial of Dedan Kimathi (1976) from my mother’s library, my eight-year-old mind trying to understand what it was about; and reading I Will Marry When I Want and A Grain of Wheat (1967) for my high school exams—lone African texts awash in a sea of English books. This is how most of the reflections in Reflections on His Life of Writing begin: with each individual’s recollection of their first contact with an Ngũgĩ text and how it touched their life—in the making of their identities, the shaping of their politics, and their pursuit of new forms of writing in the context of decolonisation. For many of the contributors, Ngũgĩ’s books were the first to cast them as full human beings, whole and dignified: the first books that looked for them in the margins of history.

What is most significant, in any overview of Ngũgĩ’s work, is the relationship that becomes apparent between the African literary project on the one hand, and the building of a nation on the other; between speaking truth to power on the one hand, and leading the project of decolonisation on the other. In his chapter, titled ‘Ngũgĩ at Work’, documentary filmmaker Ndirangu Wachanga muses about the crossroads where Ngũgĩ’s work is situated:

His biography provides revealing insights about the deployment of memory, and the role of memory in the evolution of the African nation states, allowing us to evaluate the relationship between the state and the and the African memory project. If the process of becoming of most African nation states continues to be defined by an unofficial programme of forgetting, Ngũgĩ’s biography invites the public to resist the urge to forget—rather to remember.

Freedom, nation-building, writing: what has been essential, indeed central, to liberation is the ability to imagine it, to cast a vision of it while also having an immediate picture of what it is like to be on the other side, cast outside of history. Ngũgĩ was a scribe of the nation-in-waiting, the nation-in-becoming, and he continued in his role of imaginer-in-chief after the nation became, by speaking truth to the dictator Daniel arap Moi, for whom he became a stubborn thorn in the side. It was during Moi’s long, corrupt term that Ngũgĩ was imprisoned, after the release of I Will Marry When I Want, and eventually exiled. Thus Ngũgĩ demonstrates the power of the literary in the times of the postcolony: literature retains the ability to speak, and so to organise, even where heavy censorship exists. Ngũgĩ relates an anecdote about his novel Matigari (1986):

Matigari […] goes around the country asking questions about truth and justice. People who had read the novel started talking about Matigari and the questions he was raising as if Matigari was a real person […] When Dictator Moi heard that there was a Kenyan roaming around the country asking such questions, he issued an order for the man’s arrest. But when the police found he was only a character in fiction, Moi was even more angry and he issued fresh orders for the arrest of the book itself.

—from Ngũgĩ’s Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms (1993)

The literary imagination forces the hand of censorship, plays a light on all the absurdities of the regime—but also manages to break through and become a vehicle for ordinary Africans of resistance and freedom of expression.

Ngũgĩ insisted, when he joined the University of Nairobi in 1967, that the Department of English be restructured, and along with Henry Owour Anyumba and Taban lo Liyong

presented a memo to the University College Senate titled ‘On the Abolition of the English Department’, thus sparking a shift that decentred the Eurocentric ideology that had previously dominated. Margaretta wa Gacheru, a former student, believes Ngũgĩ ‘spearheaded a cultural revolution at the University’, noting of the new curriculum that accompanied this change:

[…] the core course would be Oral Literature, which would involve every student going out and interviewing elders who had oral traditions and stories about early Kenya to share. From there the curriculum would expand in concentric circles: it would go from oral to Kenyan literature, then to the study of South, West and North African and finally to literature of the Black Diaspora and the rest of the world.

This pioneering move was echoed many years later at Wits University, Johannesburg, when Es’kia Mphahlele broke away from the English Department to form the Department of African Literature in 1983. In a chapter in Reflections on His Life of Writing titled ‘Ngũgĩ and the Decolonisation of Publishing’, editor and publisher James Currey writes of a 1962 meeting of teachers of English literature in African universities, which was convened by Mphahlele and Eldred Jones at Fourah Bay College in Sierra Leone. There, a decision was made that ‘writing by contemporary writers from Africa should be used in teaching English literature at universities in Africa, and that the examination boards in West and East Africa should choose titles to prescribe as set texts’. As a result, in 1974, 50 000 copies of Weep Not, Child were sold in Nigeria in one month, after it was prescribed as a set book by the West African Examination Board. The sales meant that for the first time Ngũgĩ was ‘within sight of being able to survive from royalties on his writing’. These events underscore the deliberateness with which this generation of African writers, teachers and publishers created connections in order to foster new curricula, in line with the principles of decolonisation.

What Ngũgĩ is mainly known for across the continent, and the world, are his ideas about language and his insistence on the use and development of African languages. His deliberate choice to write his novels in Gĩkũyũ is, or course, significant, but his collaboration with peasants at the Kamĩrĩĩthũ Community Education and Cultural Centre in rural Limuru, where he was born, to write I Will Marry When I Want, was, as Wachanga writes, ‘redemptive’. Ngũgĩ resolved to reconnect with the community he had left behind; his identity, he found, was not complete outside of this source, his umbilical cord was buried in the Gĩkũyũ language, and he renounced his Christian first name, ‘James’. Ngũgĩ’s advocacy for using indigenous African languages and creating awareness of the connection between identity and language—his fight for expression and writing in Gĩkũyũ—reflect, for him, the fight to reclaim our African selves. As he wrote in his prison memoir, Detained (1981): ‘My involvement with the people of Kamĩrĩĩthũ had given me the sense of a new being and it had made me transcend the alienation to which I had been condemned by years of colonial education.’

At the same time, it is interesting to see how some African thinkers were not in tandem with Ngũgĩ’s ideas about language, considering them old-fashioned, out of touch and perhaps not sufficiently refined. In 1994, Ngũgĩ led the creation of a revolutionary Gĩkũyũ journal, Mũtiiri, which featured creative art as well as critical engagement in the humanities. In a chapter in Reflections on His Life of Writing titled ‘Ngũgĩ and the Quest for a Linguistic Paradigm Shift: Some Reflections’, the academic and author Alamin Mazrui sketches out the intellectual deadlock that existed between his uncle, Ali Mazrui, one of Africa’s intellectual giants, who died in 2014, and Ngũgĩ in relation to Mũtiiri. Ali Mazrui suggested that the journal’s readership would increase, and its chances of survival therefore strengthen, if it was altered to become a Gĩkũyũ–Kiswahili bilingual journal: a publication with a kind of ‘inter-linguistic unity’. For Ngũgĩ, it was vital that the journal demonstrated the self-sufficiency of Gĩkũyũ. Alamin Mazrui writes that:

Underlying Ngũgĩ’s various propositions on the language question is the conviction that African languages must take on the responsibility of ‘speaking’ for the continent. In direct reaction to this, however, postcolonial and postmodern critics have argued that imperial languages too can be appropriated to serve counter-discourse functions on behalf of Africa.

It was Ngũgĩ’s contention that their exchange was rooted in the colonial idea of the centre, represented here by imperial languages, being set up against a ‘counter’. For him, the purpose of writing in Gĩkũyũ was to situate Gĩkũyũ as a centre of knowledge, therefore encouraging other African languages to become their own centres of knowledge, with the creation of an independent discourse that ‘allows Africa to set its own terms of reference’. Alamin Mazrui writes:

Counter-discourses may continue to be entrapped in the terms of reference of the dominant discourse. […] Once again, I am inclined to agree with Ngũgĩ’s claim that, as long as ideas ‘are available in African languages, even anti-African ideas, the people will start developing them in ways that may not always be in accordance with the needs of the national middle classes and their international allies’.

Ultimately, the goal of decolonisation remains to cultivate and maintain value in blackness and Africanness, and to create new ways of relating to ourselves and our cultures outside of the dysfunctions and dehumanisations of colonialism. Ngũgĩ, as Currey writes, demonstrated that ‘black people could write about themselves’ and set the terms of engagement for how the humanities, and the discipline of African literature, could lead the discourse on decolonising the continent. Ngũgĩ: Reflections on His Life of Writing brings together some of the best minds in African letters, which makes it a book to unpack for years to come. It lures you in and serves as a beacon to further brilliant work in the African literary space, as put in motion by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o some five and a half decades ago. It is a reference, and a form of reverence.

- Lebohang Mojapelo is an editor, writer, researcher and poet based in Johannesburg. Follow her on Twitter.