As part of our January Conversation Issue, The JRB Contributing Editor Efemia Chela chats to Chike Frankie Edozien about his memoir, Lives of Great Men.

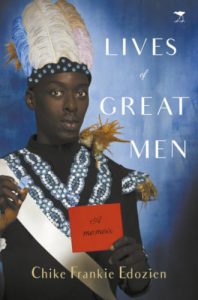

Lives of Great Men

Lives of Great Men

Chike Frankie Edozien

Jacana Media, 2018

Efemia Chela for The JRB: When did you make the decision to start writing Lives of Great Men? Was there a crucial moment? And how did you decide whose stories to include and which ones to omit?

Chike Frankie Edozien: As a result of a few recent legislative actions aimed at criminalising queer people in many parts of the African continent, a narrative of gay Africa being a foreign concept was taking root. And with legal discrimination and the horror of people being routinely shamed, it was important to explore the more nuanced reality and celebrate the small victories the community is having.

It all started to become clear to me that something must be done when, back in 2011, I was waking up to horrid headlines daily from Ghanaian newspapers that seemed to have found a new source of all their society’s ills: their gay and lesbian population. That entire summer it seemed like the only thing being debated, on TV, radio and in the papers, was gays. Not much else was going on. I ultimately put my bewilderment aside and wrote a piece on the backlash that was happening in Accra. After years of mainly ignoring this population, now there were calls for large scale criminalisation. I realised as time passed that it would take more than just one article somewhere to do these stories justice and bring nuance and perhaps even understanding to the conversation.

And doing it longform would mean a book or documentary. And so it really did take me some time—a few years, in fact. I had in my head a sense of what it should look like. Even before I finished writing a book proposal back in 2014, I had already sketched out a plan for how I wanted to tell the stories I’ve been fortunate to be a part of.

But I still had a very long to-do list. A good chunk of the memories were in the distant past, so I felt the need to go back and have a look again at places that meant a ton to me. Places I still have an emotional connection to. I wanted to reminisce about those spots that marked a change in my worldview or opened my eyes in some fashion—or simply traumatised me. One of the things I’ve learned over the years as a journalist is that one can only be so effective if you are not on the ground.

So I tried hard to look at the project as a grand reporting project, not merely recollection. I would then go and do some of my work, reporting whenever I was home to spend time with my family in Lagos or travelling some place for work. I also needed to have certain conversations again with women and men in my life at the times I was focusing on for the book. I needed to know: did they have the same recollections? Were there things and details they could tell me from their own perspective that I might have missed? Or simply didn’t remember? Yes, there were: so putting my thoughts and memories side-by-side with theirs gave me details that helped with certain chapters. And thus, I think I got a fuller, richer account of those times.

I used the same technique with my more recent encounters. In situations and conversations that I wanted to share with the world, even if I remembered them with crystal clarity I still went back to get the take of my friends and family, to ensure that what ended up in print was the most accurate rendition of those joyous or painful or hilarious times.

The JRB: How did you manage to keep up with the times while you were writing?

Chike Frankie Edozien: I knew I would end the book on a contemporary note, but at some point I had to draw a line because things were changing rapidly in some of the countries I write about, and keeping up with all of them would not have been so feasible. For instance, I write about friends and citizens who live in Zimbabwe and South Africa, and about the conditions in The Gambia. The leadership has changed in all these places, and the journalist in me would normally want to return and then to update the text, make changes, and see if there are any tangible differences in the lives of the great women and men I talk about.

I say all of this to make clear that because my process wasn’t necessarily a quick one doesn’t mean that this book was extremely difficult to write. It wasn’t. But it was not an easy one either. I was not going to rush this project. It was too important. I needed to be as meticulous as I could and had to recognise my constraints. Of course, for me, writing is rewriting. And satisfaction in my own work doesn’t come easy so it’s a lot of, ‘Try this sentence again in a different way, perhaps it would read better.’

The JRB: Although the book has ‘men’ in the title, I was happy to find a lot of women included, queer women whom you met on you travels and who grappled with some of the same issues you had yourself. Could you talk about some of the differences you noticed between African men and women living as gay in Africa and in the African expat community?

Chike Frankie Edozien: The title Lives of Great Men is from a poem called ‘A Psalm of Life’ by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. As pre-teens and teenagers we learnt and recited parts of this poem weekly in school to set us up for a life of independent thinking and making a difference in our world. Part of it reads:

Lives of great men all remind us

We can make our lives sublime,

And, departing, leave behind us

Footprints on the sands of time;Footprints, that perhaps another,

Sailing o’er life’s solemn main,

A forlorn and shipwrecked brother,

Seeing, shall take heart again.

This has always served as an inspiration to me and I’m forever grateful to my boarding school principal, the late MC Ebo, for making us recite it over and over again. And so while I talk in my book about a lot of men, I also talk about women and the people who love these great men and women. For me the ‘Great Men’ include the women who have incredibly difficult lives, because for many their own sexuality is seen as something that is in service to the husbands who will sire their children.

My ‘Great Men’ include these wonderful women who won’t conform and get married and put their own joy on hold for a society that treats their sexuality as a playful indulgence, nothing of real significance. I saw women refusing to do so. But at the same time, ‘Great Men’ includes women who have given it the ‘college try’, as Americans say. Who have married and have tried. I salute them. I salute those who have married and decided they only have one life and will seek love in the arms of a girlfriend somewhere else, the way gay guys have been doing for aeons.

I have met lesbian women who say that their husbands know but they don’t mind, and that their role now is not to embarrass their husbands by parading their girlfriends around, to have an arrangement that’s no one’s business but theirs. If a person is living within the parameters of such a marriage—’give me children, don’t embarrass me, show up when I need you and I will give you all the money you need, just as long as you don’t put our business out there’—then so be it. Not everyone can live a full open life on our continent, so those who don’t allow themselves to go mad and carve a space for themselves have my admiration. I have no judgements.

The JRB: I found Great Lives of Men to be marked by such warmth and inclusiveness. A respect for the humanity of people in the LGBTQ community, as well as allies.

Chike Frankie Edozien: Well, yes. Great Men for me include the wonderful heterosexual men and women who love their friends and family members and don’t tolerate the homophobia that is all around them and think for themselves and make decisions based on their own reasoning, not on society’s at large.

‘Great Men’ include also the many people who aren’t sure what to feel about experiences in love. They may not fit into an easily ‘checkable’ box, but they’re living on our continent. I hope this book is a way of challenging all of us to remember our own humanity and that we’re not all the same. Not all African men are irrational homophobes, but too many of us are. And it is detrimental to us. So I hope the book is a conversation-starter about celebrating our differences. When we as Africans organically celebrate and prioritise each other and our talents, the world will sit up and take notice. Right now the world simply plucks our best minds up and removes them to serve the wider world, putting Africans in Africa on the back burner. I’m not upset at the world, but it is sad when we ourselves don’t recognise what have and are losing it daily.

The JRB: What you say about loss really resonates with me, because it shows how the personal cost of homophobia is linked to the social and economic loss Africa faces. When African societies are hostile towards queer people it pushes them to seek refuge elsewhere, whether formalised through asylum or in other ways.

In the book you mention how Etienne, a former lover of yours, is Congolese but lives in Paris. He’s never returned to the DRC after leaving. Things were complicated for him in France, but in some ways better, as he could live as a gay man, have a wife, and a mistress. He was also a member of the diaspora community, but his experience illuminated that acceptance in those communities is conditional: many of them were hostile to gay people. Living in New York, what has your experience of the community and LGBTQ culture in the African diaspora been like?

Chike Frankie Edozien: The years that I’ve spent working abroad have brought me a lot of joy, but I’ve had a front row seat to the sadness of many, which later on turns to defiance and then a turning of backs towards their own countries. Etienne is a prime example of that, but at least he engages with Africa, just not with Congo DRC. I’ve seen Nigerians, Ghanaians, Ugandans and more just disengage with their countries of origin because the homophobia they have experienced from ‘home’ has made them assimilate fast. So formerly proud Africans living abroad become ‘Afropean’, American, Canadian or whatever. There was a time when people moved abroad to get an education or work experience and still used all that in service of ‘home’ somehow. These days gay men and women who leave are more firmly entrenched in these other countries. And to me, while not judging anyone, I still think it is sad for the continent as a whole.

The JRB: It’s clear that a lot of the homophobic laws in African countries are also a legacy of colonialism. This suggests that in many ways that decolonisation efforts have failed or have not been far-reaching enough in their scope. In your work and travels do you see any African countries trying to change this? Or are we still quite far away from seeing a more gay-friendly continent?

Chike Frankie Edozien: Yes we are. And no we may not be. When you look at Tanzania, for instance—a country that has so much going for it and yet is mainly in the news these days for its government officials’s obsession with gay men and women, trying to ferret them out, banning lubricants and generally just trying hard to criminalise its own people—you wonder. On the other hand, countries large and small, from Mozambique to São Tomé, do not criminalise. What is changing though is that this generation of LGBTQ Africans have refused to remain silent. We see evidence of this with all the court challenges in Kenya, for instance. From overturning the ban of the film Rafiki, to scrapping the forced anal exams, every small victory chips away at the notion ageing politicians have that scapegoating the gays gets them votes. And more importantly chips away at the fallacy that we are some sort of un-African species. It is great finally to see many who can say, ‘No. We won’t accept to be constantly demeaned by the powers that be.’

The JRB: Recently the success of Lives of Great Men took you to Aké Arts and Book Festival in Nigeria. What was it like to present the first published memoir of a gay Nigerian in a country where being openly gay is still quite dangerous and illegal? Was it a full circle moment for you as a Nigerian, bringing your work back home?

Chike Frankie Edozien: It was incredible and I was incredibly proud to launch the West Africa edition of Lives at Aké, and frankly I would not have wanted to launch any other way. One reason the Aké Festival is immensely popular with writers and creatives across the continent and the diaspora is because of the boldness of the founder and curator, Lola Shoneyin. Lola and her team have created a space where Africans of all stripes do not need permission to exist. Everyone, by the very nature of who they are, brings something to the Aké feast. I’d been a guest at Aké in 2015, talking about my work as a journalist, and an openly gay one. So I’d already been exposed to the Aké audience and been able to give my perspective, to listen, to educate myself and hopefully to educate others. There are no softball questions at Aké, not from the moderators and definitely not from the audience. Back then, it was a risk to be in Abeokuta discussing these issues, but Lola is the definition of courage and her team ensured that every voice was heard.

Since then, the volume of negative rhetoric seems to have gone several decibels up, and with the years of work and research that went into Lives it was right that Aké should be the place to present my arguments. Prior to Lives, Nigeria and indeed much of the region didn’t have contemporary LGBTQ narratives in memoir form. I was shocked when Lives came out and I was told it was the first memoir of its kind. I assumed that just because I didn’t find any models to look at from way back, that simply meant that I couldn’t find any—not that no one had written one.

Going to Lagos and talking about Lives was magnificent because of Aké. There is no room there for a majority opinion carrying the day. There is no room for vitriol. There is plenty of space for a diversity of perspectives, with none carrying more weight than any other. Aké allows creatives and those who consume their work to learn new things, new ways, and be open to that.

I cannot be sure that my work and my Aké moment in the spotlight changed the minds of the multitude of people who attended, but I know that it allowed them to ponder the issues, to ask themselves why they feel the way they do, and for the LGBTQ among those attending to see themselves reflected in the programming with dignity and pride. Many of the people who brought books for me to sign weren’t LGBTQ, and many were open after the discussion to thinking more deeply and differently on how they viewed Nigerians who are different from them, questioning why they may have had hostility in the past. And that is the glorious thing about Aké.

It is not an easy formula to replicate but honestly I was so so proud to be given a platform in a festival full of Africans, black sub-Saharan Africans, to discuss this work. And I was humbled—floored, indeed—at the warm reception I got in Lagos. Aké gave broadcast media, radio in particular, ‘permission’ to interview me and delve into the merits of the book, which even though they find controversial they went ahead with anyway.

No huge award, no shortlist accolade, no fabulous review could compare to the high I felt on the Aké stage, being publicly thanked by heterosexual readers for speaking truth to power and showing the nuances in our diversity. Being applauded at the end was the icing on the cake for a long road travelled. Only Aké could make such magic. I will be forever grateful to Lola Shoneyin and her team. They are the courageous ones.

- Efemia Chela is Francophone & Contributing Editor. Follow her on Twitter.