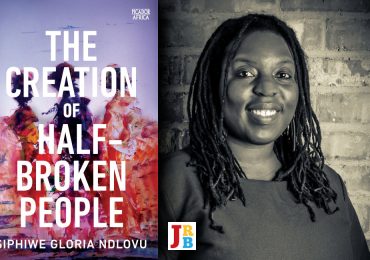

The JRB presents an excerpt from a work in progress by Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu.

Ndlovu is the author of The Theory of Flight, the first in a planned series of four connected novels. This excerpt is from the second.

Read the excerpt:

~~~

The History of Emil Coetzee

The Boy Who Was Not Frederick stood before Emil wearing a uniform that looked like it had swallowed him whole. Everything was at least two sizes too big for him: the navy blue hat and blazer, the light-blue shirt, the grey-blue shorts, the white socks, the black ‘see your reflection in them’ shoes and even the blue-and-grey-striped tie.

The Boy Who Was Not Frederick had to tilt his head all the way back to look up at his father and at that moment, looking down at the boy, Emil felt so much love; he did not know what to do with it.

Ever since the boy had bitten him on his right calf and left a permanent scar, Emil was unsure how to speak to him. He did not resent the boy’s action. In fact, Emil admired it, because in that moment of defending his mother, the boy had shown just what he was made of. There was a lot to respect in that.

As the boy continued to look up at him, waiting, Emil remembered himself in that same uniform, an unhappy boy of nine always dreaming of the elsewhere that had once been home. He sincerely wished the boy’s time at Milton Junior School would be happier than his had been.

Emil understood, of course, that Kuki had bought the uniform several sizes too big to communicate to him that her son would grow into it. That is, to communicate to him that her precious and beautiful boy would never ever attend the Selous School for Boys.

The boy was still looking up at him … still waiting.

Emil tentatively lifted up the navy blue hat and ruffled the boy’s hair. Hair like his … hair the colour of the tall, yellow, almost golden elephant grass of the savannah. He clumsily put the hat back on.

‘First day of school, eh?’

The boy nodded … still looking up … still waiting.

Emil remembered having entire conversations with his father at this age, but he no longer remembered what the conversations were about. He remembered being perched on his father’s shoulders in the Bambata, Nswatugi and Silozwane caves of the Matopos Hills, looking at paintings of the hunt. Had he and his father talked about the story of the hunt? Yes … yes … that is what they had talked about. But The Boy Who Was Not Frederick was not interested in the hunt.

The boy blinked once, twice, rubbed his nose and … stopped waiting. He looked from his father to his black ‘see your reflection in them’ shoes. He bent down to wipe off a barely perceptible scuff mark.

A moment had presented itself and been lost.

Emil felt that loss.

‘Let me look at you,’ Kuki said as she entered the room. Her voice was full of an excitement that did not betray the fact that she had spent the entire night crying because her precious and beautiful boy was going out into the world and she did not trust the world to handle him with the care he deserved. She wore a yellow terrycloth nightgown over the blue dress she would wear to drive her son to school. ‘My beautiful, golden-haired boy,’ Kuki said picking him up and hugging him. ‘Always as perfect as a picture,’ she said, kissing him. The Boy Who Was Not Frederick smiled and smiled, basking in the perpetual glow of his mother’s untainted love.

‘I’d love to take pictures,’ Kuki said, putting her son down with evident reluctance. She fixed his hair and straightened his hat. She leaned down to look at him and make sure he was as perfect as she remembered and her son seized that moment to kiss her.

Was he still kissing his mother when he was six? Emil wondered. Had he ever initiated a kiss with his mother or had she always been the one to kiss him?

‘You are the loveliest little angel in the whole wide world,’ Kuki said, as she hugged her son again and fought back tears.

Emil picked up his keys from the counter top.

‘I’d love to take pictures of the both of you,’ Kuki said, not looking at him and looking instead for her camera, which was never too far away, and which she found with a deceptively ebullient ‘Ah-ha!’

Kuki took three pictures of Emil and the boy. In all of them Emil held the boy’s hand awkwardly in his. In the first photo the boy was looking up at Emil, but no longer waiting. In the other two photos the boy was looking resolutely at the camera, in one photo he smiled uncertainly, in the other photo he did not smile.

If only the pictures had been taken earlier when the boy had been still waiting, then at least the memory captured would have been one of hope.

As Emil walked out of the front door, he knew that Kuki would take a plethora of photos of the boy, who already had ten family albums dedicated almost solely to him. He also knew that in these photos the boy would be smiling and laughing freely because, together, he and his mother would be happy in a way that they had not been able to be just a moment before … when Emil was there.

Emil, with an incessant sadness, started the car.

‘I also wore that uniform once,’ Emil could have said to the boy. But the sentence came to him too late.

- Siphiwe Gloria Ndlovu is a Zimbabwean writer, filmmaker and academic who holds a PhD from Stanford University, as well as master’s degrees in African Studies and Film. She has published research on Saartjie Baartman and she wrote, directed and edited the award-winning short film Graffiti. The Theory of Flight, her first novel, was published by Penguin Random House in 2018.