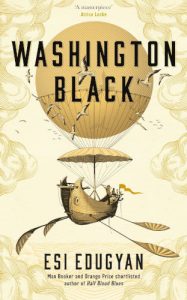

The JRB Editor Jennifer Malec reviews Esi Edugyan’s Man Booker Prize-shortlisted novel, Washington Black.

Washington Black

Esi Edugyan

Serpent’s Tail, 2018

Esi Edugyan’s strength is in her storytelling. Her books focus on characters who are exceptional, almost unbelievable, but her writing has such energy that it ensures any disbelief you may have remains suspended. But more than that, the alternative Black histories that Edugyan creates, while they may seem implausible, attest to the notion that Black excellence has been marginalised or written out of the official historical record.

Edugyan was born in Canada to Ghanaian parents. Her frenetic debut, The Second Life of Samuel Tyne (2004), is set in the nineteen-seventies and tells the story of Samuel Tyne, an Oxford-educated maths prodigy from the Gold Coast, who dresses in monstrous blue suits and a ‘mournful, pre-war bowler’, and has a habit of giggling when he is nervous. Tyne inherits a derelict farmhouse in rural Canada, in a strange town originally founded by freed slaves in the early nineteen-hundreds, now populated by sinister white people, and quits his stultifying civil service job to move there, dragging with him his long-suffering wife and his eerie and alarming twin daughters.

Despite the book’s success—including its being shortlisted for the Hurston-Wright Legacy Award, which honours ‘the best in Black literature in the United States and around the globe’—Edugyan struggled to secure a contract for her second, Half-Blood Blues. When she finally did, in a plot twist worthy of her own work, the publisher went bankrupt weeks before the book was to be released. It was eventually published in 2011 on a small print run, and quickly became the number-one selling book in Canada, winning the Scotiabank Giller Prize, the country’s richest literary award, and being shortlisted for a number of others, including the Man Booker Prize and the Orange Prize for Fiction.

Half-Blood Blues is a more assured work than The Second Life of Samuel Tyne. The plot centres around two African-American jazz musicians who find themselves in Berlin at the outbreak of World War II, and chronicles their stubborn quest to continue making music as the political situation becomes more and more dangerous. Adding to the precariousness of their situation is the fact that their jazz band is made up of Jewish and non-Jewish German musicians, as well as a shy, nineteen-year-old, mixed-race German called Hieronymus Falk, whose heritage has rendered him stateless by the Nazis. He also happens to be the as-yet-undiscovered greatest trumpet player of all time. Half-Blood Blues maintains the liveliness of Edugyan’s first novel, but it is less scrappy and digressive, and offers a rare insight into the Black German experience, as well as a powerful account of friendship and the deception of memory.

In Edugyan’s new novel, Washington Black, which was recently shortlisted for the Man Booker Prize, we meet George Washington Black, known as Wash, an eleven-year-old field slave in eighteen-thirties Barbados, who is taken under the wing of an eccentric gentleman inventor called Christopher ‘Titch’ Wilde. After a brush with death that leaves Wash’s face badly burnt, a friend of the plantation owner shoots himself with Wash the only witness, and he and Titch are forced to flee the plantation. They do so in a hot air balloon, the ‘Cloud-cutter’—a pioneering flight that goes undocumented in the history of aviation, as the pair crash into the ocean. Wash then travels to Virginia and the Arctic before ending up in Nova Scotia, where he falls in love with Tanna, who turns out to be the daughter of a brilliant marine zoologist he has admired since he was a child. Tanna and he take another cross-continents trip, to Amsterdam and Morocco, in search of Titch, and together they establish the world’s first aquarium in London.

Summarising the plot of Washington Black emphasises how improbable the story is—but is it any more improbable than, say, Oscar and Lucinda transporting a glass church by boat to Sydney, or The Sellout’s speculative suggestion that the reinstatement of slavery might actually lead to social uplift, or Colson Whitehead’s counterfactual fantasy The Underground Railroad? In some ways Washington Black is a typically improbable Booker kind of book. Of course, it seems unlikely that the unlettered slave boy whose story we are following would turn out to have an exceptionally keen scientific mind and remarkable artistic ability, but on the other hand, how unusual is it, really, for a story to begin with a seemingly unimpressive child who turns out to be surprisingly and miraculously brilliant? Edugyan is writing back to familiar myths of exceptionality—Mozart, Einstein, Harry Potter—but such exceptionality is all the more striking when originated in a Black protagonist and juxtaposed with racial domination.

Because Edugyan teases out the stories of Black people in a white world, her stories are elaborated by history. Washington Black is, on the whole, a lighthearted novel, but Edugyan does not shy away from depicting the brutality of slavery and the disorientation and heartache of black life in the colonies in the nineteenth-century. Take, for example, the character of Big Kit, the fierce and mysterious slave woman who takes care of Wash during his childhood:

In the smouldering fields she would glisten as if oiled, tearing up the wretched earth, humming strange songs under her breath, her flesh rippling. Some nights in the huts she would murmur in her sleep, in the low, thick language of her kingdom, and cry out. No one ever spoke of that, and in the fields the next day she would be all scorched fury, like a blunt axe, wrecking as much as she reaped. Her true name, she once told me, whispering, was Nawi. She had had three sons. She had had one son. She had had no sons, not even a daughter. Her stories changed with the moon. I remember how, some days, at sunrise, she would sprinkle a handful of dirt over her blade and murmur some incantation, her voice husky, as though overcome with emotion. I loved that voice, its rough music. She would suck air through her teeth and squint up her eyes and begin, ‘When I was royal guard at Dahomey,’ or ‘After I crush the antelope with my hands, like this,’ and I would stop whatever task was at hand, and stand listening in wonder. For she was a marvel, witness to a world I could not imagine, beyond the reach of the huts and the vicious fields of Faith.

Kit is a fascinating and tragic character, by turns violent and tender, whose trauma is so grave that on the rare occasion she does articulate her past, fact and fiction are indistinguishable. With the plantation under the management of a new and unusually cruel master, Kit plans to kill herself and Wash, so that they can be reborn in her homeland:

‘If you dead, you wake up again in your homeland. You wake up free.’ I made a little shrug of one shoulder at that, and she felt it, and turned my chin with her fingers. ‘What is it, now?’ she asked. ‘You don’t believe?’

I did not want to tell her; I feared she would be angry. But then I whispered, ‘I don’t have a homeland, Kit. My homeland here. So I wake up here, again, a slave? Except you won’t be here?’

‘You come with me to Dahomey,’ she murmured firmly. ‘That how it works.’

‘Did you ever see them? The dead, waked up? When you in Dahomey?’

‘I saw them,’ she whispered. ‘We all saw them. We knew what they were.’

‘And they were happy?’

‘They were free.’

But when a number of slaves have the same idea and there is a rash of suicides, the master organises for one of the dead slaves to be decapitated in front of the whole community, as according to their beliefs you cannot be reborn without a head. He tells them:

‘I will do this to each and every new suicide. Mark me. None of you will ever see your countries again if you continue to kill yourselves. Let your deaths come naturally.’

I stared up at Kit. She was peering at William’s head on its spike, the bulge of its softening flesh in the sun, and there was something in her face I had not seen in her before.

Despair.

We see glimpses of potency and insight in Big Kit, but ultimately her circumstances overpower her fate. Later, Wash reflects on his life on the plantation:

I looked instead to my hands, thinking of the years spent running, after Philip’s death. And I thought of what it was I had been running from, my own certain death at the hands of Erasmus. I thought of my existence before Titch’s arrival, the brutal hours in the field under the crushing sun, the screams, the casual finality edging every slave’s life, as though each day could very easily be the last. And that, it seemed to me clearly, was the more obvious anguish—that life had never belonged to any of us, even when we’d sought to reclaim it by ending it. We had been estranged from the potential of our own bodies, from the revelation of everything our bodies and minds could accomplish.

When Wash leaves the plantation, however, these tragic notes all but fall away, and he becomes a globe-trotting, boundary-breaking adventure hero, if something of an unwilling one. He even gets the girl, despite his disfigured face.

As the novel progresses, it is drawn along by strange coincidences and cloak-and-dagger contrivances, and the novel’s villains, the plantation master Erasmus Wilde and the slave-catcher John Willard, are almost cartoonishly evil. Despite the sensitivity and elegance of the writing, Washington Black does skirt dangerously close to melodrama at times. But by lining her work with narrative irreverence, Edugyan emphasises the vitality and, critically, the individuality of the Black people whose stories she tells.

This year, the Man Booker judges raised lettered eyebrows by including on the longlist its first ever graphic novel, in Nick Drnaso’s Sabrina, as well as Robin Robertson’s genre-busting novel-length poem The Long Take, and Belinda Bauer’s Snap, one of the few crime novels ever to be considered for the prize. Washington Black is arguably even more ‘readable’ than Snap, but unlike the latter book it does retain the ‘literariness’ one would expect from a Booker longlistee. This does not, however, emanate from any attempt at literary experimentation on the part of Edugyan. Despite Washington Black’s turbulence, it is a straight story. Rather, the novel’s merit stems from the depth of its characters and Edugyan’s striking powers of observation. Most importantly, Washington Black’s distinction emerges from Edugyan’s singular brand of revisionist history, which demonstrates that the rediscovery of the ordinary does not preclude the extraordinary.

- Jennifer Malec is the Editor. Follow her on Twitter.

Sorry wrong email