The story told in The Lost Boys of Bird Island warps South Africa’s history beyond the nightmares of colonialism and apartheid, writes Richard Poplak.

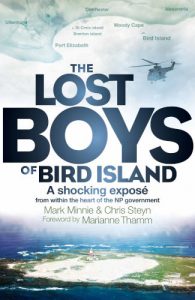

The Lost Boys of Bird Island

The Lost Boys of Bird Island

Mark Minnie and Chris Steyn

Tafelberg Publishers, 2018

1.

If all portrayal is fiction, especially the most accurate, then that is perhaps why The Boys of Bird Island—a rigorously reported account of the National Party regime’s most gruesome death rattle—reads like a seamy Swedish thriller. It has all the elements of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo-ish pulp: a soaked cop; a determined journalist; a government cover-up that goes right to the top, IF NOT HIGHER.

Meet Mark Minnie, a narcotics officer working the mean streets of apartheid-era Port Elizabeth. He’s an unrepentant piss-head, a shagger of nurses, bargirls and other lower-middle-class professionals (most of whom have now been replaced by apps). He has a heart of gold, certainly, although he’s not above engaging in the occasional afternoon bar tussle. ‘Action and reaction,’ he writes of a fight. ‘My slamming the ashtray into the ox’s face resulted in the concomitant reaction on the hand holding the weapon. I suppose no good deed goes unpunished.’ James Ellroy crossed with Leon Schuster, divided by Dostoevsky: this is the most South African book I think I’ve ever read.

Wielding a broken finger and a permanent hangover, Minnie is ordered by his brigadier to investigate a case concerning a Coloured teenager who has been hospitalised for an injury so horrific it almost defies description: a gun was inserted in the boy’s anus, and either accidentally or deliberately discharged. According to the victim’s brother, there is a sex ring operating in Port Elizabeth, one that pimps out poor Coloured youths for a shadowy cabal of powerful men. Minnie is thus plunged into the city’s demimonde, on the trail of a rich dandy known around the dive bars as Uncle Dave. ‘I didn’t want this investigation,’ growls Minnie. ‘The powers that be threw it at me. I’m a narcotics agent. But stuff them all now. No one us going to take this case away from me. It’s mine. I want to find the men that did this. I have to find the men that did this.’

For Minnie, the case has a personal dimension. In a series of brave and brutal passages, he recounts being raped as a boy by two teenagers in the basement of a neighbour’s home. ‘This one is for me and all the other children these fuckers prey on,’ he writes.

The first fucker in question—Uncle Dave— turns out to be Dave Allen, a well-connected police reservist, head of the police diving unit, and local businessman with considerable National Party ties. He’s also known in underworld circles to be a committed pederast. Allen owns a number of off-shore guano concessions, including one on Bird Island, a breeding ground for the Cape gannet. There are rumours that Allen takes children there for his dark perversion on the ancient South African braai ritual: eat, drink, underage sex orgy. In several Netflix-worthy peak-TV-cliffhanger passages, Minnie comes close to identifying one of the men who is a regular at these gatherings. The kids call him Ore, or Ears, and he is known as the true sadist in Allen’s cabal. Minnie christens him ‘Wingnut’. The rest of the world knows him as General Magnus André de Merindol Malan, head of the South African Defence Force, and the second most powerful man in South Africa.

Minnie slaps the cuffs on Allen, who promptly sings like one of the gannets on his infamous island. But before Minnie can dig much further, and following Allen’s arraignment, the businessman is found dead on a beach, a single gunshot wound in the centre of his forehead. In his suicide note, he attributes his decision to a bad back. Minnie is unconvinced. ‘I assume Uncle Dave would have held the barrel of the gun flush against his forehead before pulling the trigger,’ he muses. ‘If so, then why aren’t there any gunpowder burn marks to the skin around the point of entry?’

Nope.

2.

Flash cut to Noordhoek, Cape Town. Meet Chris Steyn, a respected and capable hard news reporter working for the Cape Times. Steyn is newly returned from exile—she undertook a forced vacation to London after displeasing the apartheid regime—and she’s thrilled to be back home. That sensation doesn’t last. (With its dual and duelling authors, The Lost Boys of Bird Island comprises a game of exquisite corpse, played between cop and journalist as they unwind the case from different, and sometimes opposing, perspectives. The book’s Foreword is written by Marianne Thamm, one of South Africa’s finest-ever muckrakers, and this reviewer suspects she is at least partly responsible for wrestling this beast of a text into coherence.) Steyn’s prose is more sober than Minnie’s (in more ways than one) and the two contrasting voices don’t make for a particularly successful narrative format. But the story she tells links up with her counterpart’s in a near-unbelievable fashion.

Barely a month after Allen’s death, Steyn finds herself investigating perhaps the most famous suicide of the apartheid era, that of National Party Minister of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, James Wiley. Much like Allen, with whom Steyn learns he shared business and personal interests, Wiley has died from a single, apparently self-administered, gunshot wound to the head. There, are however, inconsistencies in the story being peddled by state security. Wiley was an inveterate note-taker and -sender: it seemed totally out of character for him not to have explained his decisions with an elegantly-phrased missive. More sinister still, the door to his room appears to have been locked from the outside.

Double nope.

Wiley, as Steyn points out, seemed to have lived a shadow life, spending beyond his means and engaging proclivities that, let us just say, were not quite in line with Dutch Reformed Church mores. Steyn’s reporting reveals inviolable links between Allen and Wiley, and those links may have served as their mutual death sentence. After all, as she later notes, there is evidence to suggest that the regime’s covert death squads were not above perpetrating the occasional assisted suicide for ‘national security’ purposes.

Steyn learns that the connection between Wiley and Allen was premised less on sex than it was on money. Allen, who regularly spoke at South Africa’s Parliament, had used his connections with the environment minister to acquire the aforementioned guano-rich sites, plus an underwater farming concession in Saldanha Bay. Wiley, it seemed, had visited Bird Island, and had been subjected to all sorts of pressure for his, shall we call them, predilections. Should these connections (and predilections) have been exposed, they would have had major implications for the outcome of the whites-only national elections in 1987. The country was burning, the National Party’s constituency was gatvol, and a sex-with-underage-boys-and-corruption scandal would not have played well in the press.

3.

I’m not certain whether comparative corruption is an academic field, but perhaps it should be. After reading The Lost Boys of Bird Island, the Guptas commandeering the Waterkloof Air Force Base for a garish parvenu wedding suddenly doesn’t seem like as much of a big deal. What seems certain is that Allen, along with Wiley, a second Cabinet Minister who goes unnamed because he is still alive and presumably bristling for a libel fight, and Magnus ‘Wingnut’ Malan, travelled to Bird Island in order to rape Coloured boys. And that Malan used military helicopters for these excursions. In other words, these abuses were taxpayer-funded, implicating the ruling minority not only in the horrors of apartheid, but also in its ghastly sideshows.

In a manifestly corrupt system, one in which there is zero oversight or accountability, there is no pit in Hell that can’t be mined for weekend entertainment purposes. But how does one even gauge Bird Island on the corrupt-o-meter? Given that this story has remained buried for so long, what does it say about our fantasies of healing and reconciliation? To what degree does this warp our history beyond the nightmares of colonialism and apartheid?

The Lost Boys of Bird Island is thus one of the most important works of non-fiction to have been published during South Africa’s democratic era. But it arrives with a grim coda that doesn’t make it into the manuscript: several weeks after its publication, Mark Minnie was found dead in Port Elizabeth. Cause of death? Suicide, of course.

Triple nope.

The similarities between the deaths of Allen, Wiley and Minnie are not just chilling, they seem like an overt provocation from certain forces still extant in this country. Minnie, after retiring from the SAPS, had been living abroad. His return to South Africa was meant to be something of a triumph: finally, the story burning inside would be told. But there is, of course, more to the tale—the naming of the nameless minister, for instance. And Minnie was digging further when he met his end.

If anyone ever tells you that apartheid and its attendant pathologies belong to the past, whack them over the head with this book, along with the press notices of Minnie’s untimely death. The regime literally still lives with us, inside us. In the absurd, fiction-worthy truth of The Lost Boys of Bird Island, we find a country stranded in a kind of interregnum between what we know and what we don’t want to know. As former president Kgalema Motlanthe recently noted, ‘The poet Keorapetse Kgositsile always wrote “PastPresentFuture” as one word—it is always now.’ In such a place, books like The Lost Boys of Bird Island function as both a timepiece and a map. Without them—without the ability to pinpoint where, and when, we are—we don’t know it, but we’re lost.

- Richard Poplak is a filmmaker and journalist. His latest book is Continental Shift: A Journey into Africa’s Changing Fortunes, co-authored with Kevin Bloom. Follow him on Twitter.