Yemisi Aribisala recalls her first encounter with Little Black Sambo, and asks: Who is responsible if the image of the black child is marginalised?

You eat a small child head first. Because this is a literal statement, not some riddle or figurative play of words, the question of books for children of colour needs addressing now-now.

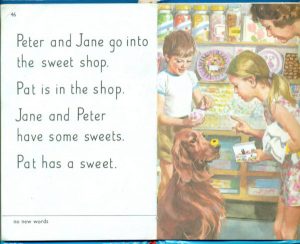

When I was a child, the most efficient way to swallow me whole was to present me with beautiful illustrations. My imagination kicked vigorously into gear with the help of the sweet shop in the Peter and Jane reader. I spent days on end staring at one tantalising page in particular, every sweet accounted for in the palate of my mind’s eye. In real life I would have had to show restraint. An adult would escort me to the shop, and would hover and allow me just one or two sweets. And adults love to spoil the sacrosanctity of an experience with talk of money. They’d talk about what they couldn’t afford, point out what isn’t good for you, raise the issue of cavities, and you would ultimately be disgusted with them. In the pages of the book, on the other hand, I could do what I wanted. I could take my time walking around the shop, climb to the jars at the top, scramble up with my feet balanced on the wooden shelves. I could have as many sweets as I wished.

In Jane’s hands were some of the sweets: a box of liquorice allsorts, with a yellow-and-black one placed by the girl on the nose of Pat the dog. I was mesmerised by these sweets in particular, and I gave them an identity that, as I would later discover, had nothing to do with what they were really like. They were not available in any shop I had ever visited, growing up in Lagos. I had never seen them outside the pages of the book. I had at least heard the word ‘liquorice’—well, read it, in The Magic Faraway Tree by Enid Blyton. That licorice appeared in both books was ample enough recommendation of its merits for me, quite apart from the fact that what you don’t have and have never seen becomes more esteemed than what is readily available to you.

I was a teenager before I tasted liquorice. The experience collided barbarically with every beloved memory I had of haunting the sweet shop in the Peter and Jane book. Liquorice turned out to be the oddest-tasting, most Nigerian-palate-confounding sweet thing that I had ever put in my mouth—aniseedy, salty, medicinal, awful. I was near inconsolable. What was lost was priceless, the images of gold, pink, yellow, red, black. The spirals of sweets in the background arranged in that round tin—possibly a ruse too! The scraping noise of jars being opened in my head a million times over—desecrated! There had been an unspoken agreement between Peter, Jane and me. We had agreed—hadn’t we?—that at the end of the beautiful day that had been documented in the pages before, we were all rendezvousing in the shop to examine every repository of deliciousness, and they were supposed to choose the best, most mouth-watering box of sweets on my behalf. On behalf of every child that opened that reader.

Thus the excursions I had undertaken to a beautiful fantasy world were retrospectively ruined. I had to travel precious years to discover that Jane and Peter had chosen something that could never factor in any fantasy about any sweet thing in any world that I inhabited. The betrayal was deep, because the investment was costly.

Likewise, the investment of any child’s intellect and imagination in the images on the pages of any book are wholehearted, unreserved, indelible—especially where ubiquitous themes are concerned: other children, their acknowledgement and welcome, play, sweets, love, laughter, falling down and scraping a knee, crying; the self image and soul image reflected back from the mirror of the pages. The images of the soul that we glean are of course the highest stakes: transcendence is at stake. Liquorice is obviously much lower down. Even so, when I think of how long the bewitchment of that one image travelled with me from childhood, it Had Me. Had me so wholeheartedly that it had the power to disappoint so powerfully, so many years later.

In the late nineties I spent seven months in the home of a friend in England. She loaned me one half of her home to write in. Her half—which was a full cottage—had bookshelves lining the walls on the way through to the sunroom. One day, as I reached for a book from the shelves, almost by instinct, my hand came back holding a small blue book with the title The Story of Little Black Sambo. Immediately I was taken aback. ‘Sambo’ was a word I hadn’t heard in years. It evoked the imported British sitcoms of my childhood in Lagos, when from 7 pm every evening, if there was electricity, we would camp out in front of the television to watch Love Thy Neighbour, Mixed Blessings, Mind Your Language, comedies that emerged from a decade of acute racial tensions in nineteen-seventies Britain. The anti-immigrant passions had been encouraged into the open by British parliamentarian Enoch Powell’s 1968 ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. ‘Sambo’ was that word that old-school Socialist Eddie Booth frequently tossed across the fence at his hated black Tory neighbour Bill Reynolds in Love Thy Neighbour. Bill would respond in racial-slur kind with the word ‘honky’. Sitcom audiences were cued to roar with laughter at words like ‘coon’, ‘wog’, ‘paki’ and ‘nig-nog’, among others, in these comedies. And we naively laughed along, until a relative who had been living in London came to stay and broke down the politics of race and their real consequences, the true context of what we were entertaining ourselves with four thousand miles away.

The images on the television were weightier than the words. Even at that time, I found it hard to turn my heart away from Mixed Blessings because we had watched it for so long, and because of the romantic relationship between Susan Lambert and Thomas Simpson, and because Ghanaian actor Muriel Odunton (who we presumed to be ‘Oduntan’—Yoruba, Nigerian) played Lambert. As with all children of my age, in my class, of middle class parents with televisions in their homes, our understanding was simply that some farcical white people had some irrelevant problem with the existence of black people. It was entirely outside our radius of worry and even belief. These people were spouting words that we had never thought to look up in dictionaries. It was comical and deserved to be laughed at. Even if we didn’t take sides with the people on television who looked like us (and we most certainly did), clearly the problem was with white people. We couldn’t see beyond Leo Sayer singing ‘You make me feel like dancing’ in white flares before our bedtime. Occasionally, in our reality, we saw white men roasting in the sun in Lagos, dissolving into the ground in sweat and wilting khaki, hiding out in UTC supermarket in the meat section. Who could take seriously their denigration of blacks?

The image on the cover of Little Black Sambo I held in my hand was of an ugly boy, or man; he was ambiguous in his physical development. His clothes were primitive. The incongruous wavy wig on his misshapen head was confusing. The unfortunate head often changed shape as the story moved along, but never from the beginning to the end of the story did it come right. Little Black Sambo’s lips were thick and bright red, and made up in their visibility for the missing contours of his face. His jacket was the same unsettling shade as his plush lips. Perhaps I am overreacting about how some of his features disappeared into the page, about how the lips and the whites of his eyes popped out in contrast; this may merely indicate the rudimentary artistic skill of the author, Helen Bannerman. But for the same length of time that I had been reading books, I had been a connoisseur of imagery and beauty. I was not imagining that Sambo’s features disappeared into a flattened brown flexible plate of a head, while in contrast Jane and Peter had normal heads and glossy hair and painstakingly illustrated beauty.

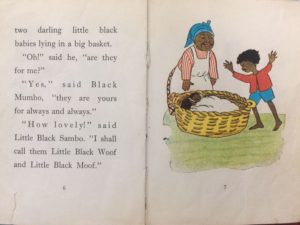

I turned the pages. Sambo’s parents were Black Mumbo and Black Jumbo. Was I to understand that this little Sambo fellow had been born of Mumbo Jumbo, in other words nonsense, rubbish, insignificance, incoherence? Unlike my initial readings of Peter and Jane, this rumination was not in any way childlike. I was no longer a child. I wasn’t just looking at pictures, I was reading words and mixing the two impressions, I was swimming in the undercurrents. I was fully conscious of everything the book was presenting to me. That which enthralled me fully, that which made little impression. That which was attempting insidiously to penetrate under my black skin. Did it in fact put me at a disadvantage that I was an adult, or was I, with my years of experience, in a better position to understand what in this book was attempting to eat children? What came of the terminological combination of Mumbo and Jumbo? Were there no dignified names available to this author? Real people’s names? Peter? Jane? Abdul? William? The parents were gibberish, an indecipherable mix, and the child was true to his ancestry—an unpalatable, unsightly mixed bag. Even dogs in books were given human names. What were the hole-and-corner messages here?

Etymologically, Sambo could be derived from Zambo, a Latin-American Spanish name meaning mixed African and Native American, or Nzambu, a Kikongo word for monkey. In the book, Sambo is said to be a South Indian boy. Before Bannerman chose the name for her little black creature, in 1899, she must at least have heard of William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1848), and perhaps also Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852)—and both of these books feature characters called Sambo. The name already had a history.

After my initial shock at the brazen representation of blackness, of parenthood, of human anatomy and the existence or non-existence of elbows in Little Black Sambo, my next question was whether the image was truly human. I link that rumination to my encountering of the ‘golliwog’ as a child. The golly, as it is now euphemistically known, is no doubt an anti-black caricature as disreputable as Little Black Sambo, but I never read Enid Blyton’s The Three Golliwogs stories, where these toys took human form. I had only read a story in which the golliwog was a doll alongside all the other legitimate caricatures of humanity in the nursery: all the other toys, in other words. A golliwog was only as truly representative of a human being as was the rag doll with stitched red patches for cheeks. Little Black Sambo was worse by degrees for many reasons, not least because he was presented as a real boy stunted in looks and development from the first premise till the last.

I asked my host sheepishly why she had the book in her possession. There was an inconsistency for me in the fact that she had been married to a black man, had black children and grandchildren, and had given me half of her house; had befriended me without any hint of racial prejudice. But this book would never have been found in my house, to be read by my children or grandchildren. She gave me an explanation that I heard again from my Little Black Sambo-owning neighbours in Calabar, Nigeria, twelve years later. These neighbours were a marriage of a Cameroonian wife and a British husband, their children two incredibly beautiful little girls to whom no book illustration could ever do justice. The father’s explanation was that the books were in their possession because they had slinked under the door, into the normalcy that manages to exist in the liminal spaces of an interracial marriage that has produced children. The Caucasian parent in the union wanted to give the gift of night-time reading to their children. That parent’s parents, in their time, had been able to walk into any bookshop, any day of the week, in any part of Great Britain and find every expression of three-dimensional humanity, of love and power and beauty and achievement and strawberries and parties and exploding sweets, and overcoming evil, and beautiful parents with real names, holding and loving beautiful children in the pages of books. But these books were always and only about white people.

With tenderness these modern parents conjured up memories of their own parents who, even if they were stiffly formal in the expression of emotion, would let their guard down and lend the crook of an arm for pleasurable minutes at bedtime, hold them, animate words that were intermingled with heartbeats until they fell asleep. The Little Black Sambo books were, therefore, a desperate compromise, the kind of compromise you reach when you have searched and searched and searched every bookshop for a children’s book containing your partner’s image. Just as the white person was missing from our day-to-day life in Lagos, the black person was missing from the life of children’s books. Or she was Little Black Quasha, illustrated by Helen Bannerman. You knew, or you hoped, that the sinister nature of the compromise would not matter to the child that was being read to, because it is easy to eat children—head first—with words, and then with embraces. Thankfully, children are always dropping nuances out of the book bag as they carry it along, filling in lacunas of good intention where they don’t exist. Imagining that liquorice is the most delicious sweet thing in the universe.

This has been proven time and time again. If The Pied Piper of Hamelin is really about immigrant children being lured away to be sold, a child doesn’t know it. She is concentrating on the one child who has been left behind, she is standing with him and consoling him with the deep intuition of injustice that comes naturally to children. If Roald Dahl’s stories are cruel they are usually so on behalf of the small person, who needs to be helped to a roundabout justice in the towering world of unjust adults. The presence of cruelty in children’s books, which in any case is not absent from children’s real lives, is fine, even functional, if it is accompanied by some idea of justice. The villain is overcome. The slow child is recognised and earns a true friend. The dog finds a home before night falls. The girl who can’t walk realises she doesn’t need to walk; she is granted wings, she soars. But where is the justice for the image of the black child, longstanding justice, justice that reaches back decades to fill in the blanks of humanity? Eileen Brown’s Handa’s Surprise, Faith Ringold’s Tar Beach, Ezra Jack Keats’s The Snowy Day, Mylo Freeman’s Princess Arabella’s Birthday, Malorie Blackman’s books—they are here, but they don’t reach back far enough or stretch wide enough to displace books like Little Black Sambo from the bestsellers lists, from Amazon, from still being sold on Wordery. From still being bought at all and read to children.

I stole my Calabar neighbours’ copy of The Story of Sambo and the Twins. I think I hoped I would find justice in it. Perhaps, I thought, the first book was born of self-indulgent ignorance. Maybe in this book Bannerman’s small-world viewpoint and representations develop beyond the primeval exoticising of people who look different. Perhaps the problem was that there was no Wikipedia page for the name Sambo in her time. Perhaps, after writing the first book, she visited the homes of people from the Tamil ethnic group, among whom she lived in Madras, with her officer/physician husband. Perhaps they met real Indians, learnt their real names, ate something they served her that didn’t have tiger ghee in it, noted for the first time their hosts’ beautiful clothes.

I also think I stole the book because I believed that I would never be able to buy a copy of it—that I would not find a book, so simplistic and patronising even to small children, for sale in the present day. That it was a relic whose inappropriateness had been long outed. After all, there were very few things, these days, you could get away with putting ‘little’ and ‘black’ in front of that were not ‘dress’ or ‘book’. I later easily found a copy of Little Black Sambo on Amazon, of course.

Then too, I stole the book because I felt my reaction was not matched by other people’s reactions. Perhaps people didn’t care what was eating young children. First impressions were what seemed to count. The undercurrents didn’t. Very few parents paid deep attention to what they gave their children to read. Some believed you couldn’t protect children from being eaten. If they were meant to survive ideological monsters, they would. Like vaccines, whatever they were exposed to had less chance of killing them later.

Wikipedia says Bannerman’s books are about Indians and their cultures. Little Black Quibba (another boy in the series) has a ‘Scholar’s Choice Edition’ because it is noted as being ‘culturally important and part of the knowledge base of civilisation as we know it’. Her books are bestsellers till today, and the controversy around the name Sambo was dealt with by a new version of the book titled The Story of Little Babaji, illustrated by influential American illustrator Fred Marcellino. That new version did not replace Little Black Sambo, however: it is just sold alongside it.

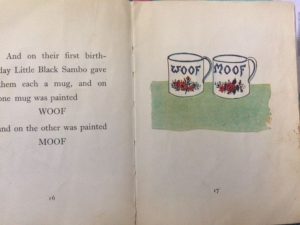

Finally: I stole The Story of Sambo and the Twins because I wanted my children’s opinion on it—a contradiction, I know, when I have said I didn’t want the book in my house. My defence is that my elder daughter was already too sophisticated to be eaten by the likes of Bannerman. More significantly, she too is Nigerian and, lastly, was unaffected by the nostalgia of a parent’s soft reading voice psychologically and emotionally recommending the book to her. In her opinion it was a silly story that only raised an eyebrow at the point where Little Black Sambo is given twin babies, Little Black Woof and Little Black Moof, as gifts by Black Mumbo. But she is part of a generation that is likely to very quickly compare the words and illustrations in books to those on television and the internet. If the narrative is nonsensical you don’t waste time, you change the channel and don’t think too much about it. This is in no way an advantage, in my opinion. I asked her whether the fact that human babies were likened to puppies in the book made an impression on her past the silliness: was it not much more insidious and deliberate than silliness? Had she ever read or seen a narrative about white people where white babies were comparable to the children of dogs, given to a child only a few years older as gifts in a basket placed on the floor?

Did she understand the sacrosanctity of mothers and their images in the media, outside the media? And if a mother with the moniker Black Mumbo entrusts newborn babies to a seven-year-old child, what does that say about the mother, especially because the mother stands in a very powerful place as birther and nurturer of beings alike in appearance—probably one of the most revered cultural pillars on origin and personhood? Why this reiteration of black, black, black, over and over? Were the words ‘black’ or ‘white’ necessary in any children’s narrative? What do they add? Are people like sweets, made more appealing by meticulous descriptions of their colouring? Had she ever seen a slave narrative on television or on the internet where newborns were left with children not much older because the mother had been sold off or killed or needed to be in the field back at work? Did the mother do this willingly, smilingly, as Black Mumbo did in the book, or was she devastated? Was the grinning detachment from the fragility of newborn life by this caricature convincing? Were newborn babies given mugs resembling dog bowls with their names, ‘Woof’ and ‘Moof’, printed on them? Did babies not drink out of bottles or need breastfeeding?

Had she ever met a boy called Woof?

Was she in any way suspicious of the anthropomorphism of the monkeys that later stole the babies in the book? Had they been intentionally given more agency than Sambo? More significance than the mother, nurturer, protector, Black Mumbo? Why did these twin babies grow in the book while Sambo himself remains the same age and size from the first page till the last? Why did the twins end up calling Black Mumbo and Black Jumbo (the absent father who only turned up at the end to do a dance and eat pancakes) ‘Mother’ and ‘Father’ on the last page of the book? Were Mother and Father not functional names? Did they not indicate care and responsibility? If a black mother who looks like yours has no real name or agency or responsibility or chance of transcendence what does that say about you, your image, your influence in this world, the possibility of your own transcendence?

As compared to the thousands of examples of anthropomorphism that she had seen on television and in books relating to dogs and androids, inanimate objects, hungry dragons and aliens from Pluto compassionately given citizenship on Earth, how or where did the black child rank in humanity, in the narrative? And today?

My daughter couldn’t give me the answers I needed or the ones that instinctively felt right.

Eating children is an adult preoccupation. The sleight of hand in children’s books is that while the child is allowed to outwit the anthropomorphic beast, with their tools of innocence—or, more frequently nowadays, tools of magic—there is always a hidden upper hand. The layers of meaning are put in place by the author, and remain potent even if the adult standing between the narrative and the child, helping to interpret, is nostalgic in her choices.

For a long time now we have attempted to close the antithetical distance between adults and children in children’s books narratives, in an attempt to reflect children’s increasing exposure to adult themes in the real world. We want to protect them and educate them, to call a halt to that nonsense about Prince Charming riding up and saving the princess, provide more images of black hair in its intrinsic beauty, create more self awareness about the body—where ours ends and others’ begin. We want children to love their image, and not to discriminate against other people’s shapes, sizes, languages, colours. Ultimately we want them to be kind to others, and we want to do all this without being moralistic. But nostalgia and passivity mean that our role as guardians of the undercurrents has become absent minded.

My last question to my daughter was: Why do we instinctively trust the authors of children’s books? We presume they are good people. They love children. They want a just world. They are committed to racial equality and morality. We believe they can be trusted with the expression of culture.

The image of the black person, for as long as books have existed, has been dimensionally marginalised. I wondered whether it was our passivity that has got us to where we are today, arguing with the Carnegie Medal, one of the UK’s most prestigious children’s book awards, about the exclusion of BAME work (the prize’s 2017 longlist did not feature a single BAME author; the 2018 longlist of twenty featured three; in its eighty years an author of colour has never won it). The prestige of the Carnegie Medal means it affects how school libraries are stocked, what a mother will buy in a bookshop when she sees a lovely colourful Carnegie stamp on the cover. Its choices, like those of other sentinels in the production and sale of children’s books, affect the availability of black images for reading children.

Essentially, in my questioning, I was asking my daughter to explain the loss of adult attention. Adults are capable of proactively reading narratives at all levels of life, while riding the waves of social media, listening to CNN, reading the papers, feeling for the mood of the world and judging it. I was, therefore, asking the wrong person.

Children are rightly preoccupied with justice. Adults are responsible for providing options for the child’s mind—for how the children are eaten. I don’t have a conclusion, but I will ask a final question: Who is responsible if the image of the black child is marginalised?

- Yemisi Aribisala’s debut book of essays, Longthroat Memoirs: Soups, Sex, and the Nigerian Taste Buds, uses Nigerian food as an entry point to thinking and understanding culture and society. Her upcoming book on Nigerian feminism, identity, migration and Christianity is to be published by Chimurenga Chronic, Cape Town in 2019. She lives in London with her children. Follow her on Twitter.