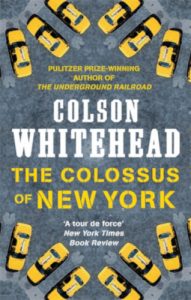

Colson Whitehead’s The Colossus of New York, reissued fourteen years after its first publication, endures in the quality of its writing and its heated restlessness, writes Wamuwi Mbao.

The Colossus of New York

The Colossus of New York

Colson Whitehead

Little, Brown, 2018

Cities are not elusive spaces, no matter what the panjandrums of urbanness may tell you. They may seem that way, because they are capacious, admitting many meanings, but to insist on seeing what exceeds us as evasive is simply to take the measure of our own insufficiency. The precept that cities make for interesting writing material doesn’t hold true for all of them—there may be a New York novel, or a Johannesburg novel, but nobody is clamouring for the great Durban novel or a set of conjurations about Portsmouth—but it has nonetheless given license to much city-centred writing over the years.

It is a truism that some cities are more culturally intriguing than others, which is why influencers and other personalities are always talking about ‘getting into’ Lagos or Berlin. Few cities, however, are as absorbed by their own mythology as New York. New York is a city treacled with representation. It is the flagship cultural project in America’s search for meaning. Everybody has an idea about what New York is, and everybody who lives in New York wants to buy into this mythology. It can be wearying: Joan Didion famously called it ‘an infinitely romantic notion, the mysterious nexus of all love and money and power, the shining and perishable dream itself’.

Cities are a harbour for easy metaphors. Here’s one: they remain a source of fascination even as their novelty wears away because they contain multitudes. Streets and avenues evoke blood vessels, which is why urban planners love to speak about vitality; and, by extension, why it’s assumed that anything written with the city as its backdrop is possessed of that same vitality. This is, of course, the animating energy behind F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, and that novel’s blueprinting of New York as the make-you-break-you hub of modern cultural capitalism prefigures our literary preoccupation with reading social reality in the writhing city.

Colson Whitehead’s The Colossus of New York, reissued now fourteen years after its first publication (and in the wake of his Arthur C Clarke Award, Carnegie Medal, National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Underground Railroad), expresses just such a preoccupation. Published in the cindering afterglow of the terror attacks that exposed the illusion of New York’s grand permanence, this book of thirteen peripatetic essays reads very much as an attempt to understand how to live on in the face of this new and unbearable knowledge. If that makes it sound like heavy weather, I’m doing the book a disservice. Whitehead’s book is not didactic: what it does is take significant points of contact with the city—bus stops, buildings, streets—and shake them free of dusty metaphor.

Colossus’s great precursor is EB White’s shimmering 1948 essay ‘Here is New York’. It was White who professed that:

There are roughly three New Yorks. There is, first, the New York of the man or woman who was born here, who takes the city for granted and accepts its size and its turbulence as natural and inevitable. Second, there is the New York of the commuter—the city that is devoured by locusts each day and spat out each night. Third, there is the New York of the person who was born somewhere else and came to New York in quest of something …

Whitehead’s book is possessed of the same heated restlessness, and it spreads itself over a larger canvas with the same captivating attention to detail. The book begins with a consideration of place. In ‘City Limits’, the narrator declares:

I’m here because I was born here and thus ruined for anywhere else, but I don’t know about you. Maybe you’re from here too, and sooner or later it will come out that we used to live a block away from each other and didn’t even know it.

This is a strong opening line (New York is a city of strong opening lines, from Fitzgerald to Sinatra), but it is immediately undercut by the speaker turning their attention to an addressee. This admission of not-knowing frames what will be one of this book’s preoccupations, namely the chasm between the experiencing self and the historical Other, who appears before us with their own set of experiences and understandings about this shared city. Indeed, Whitehead’s narrator remarks that what characterises being a New Yorker is history:

No matter how long you have been here, you are a New Yorker the first time you say, That used to be Munsey’s, or That used to be the Tic Toc Lounge. That before the internet café plugged itself in, you got your shoes resoled in the mom-and-pop operation that used to be there. You are a New Yorker when what was there before is more real and solid than what is here now.

Whitehead creates a mosaic of voices for his narrative: we drop in on a stranger’s vituperations, their rebukes or resignations, and then we alight again. The effect replicates the unpredictable snippets of conversation one hears walking down a busy street. Each essay twists and winds around an urban theme, like daily routine (‘Morning’, ‘Rush Hour’), transit (‘The Port Authority’, ‘Subway’) or recreation (‘Central Park’, ‘Downtown’). Whitehead is fully aware of how these sites of meaning are tropes, but he reworks them to serve as stages for the very many private dramas that play out in the life of the city.

Neurotic New York is not by any means a new theme, but The Colossus of New York works by showing how the city’s rigid planning, its network of structures for deciding how people move and do work or recreation, are undercut by the radical uncertainty of the individual. Whitehead’s cast of eight million are united not only by the city, but more importantly by their experience of the city as a zone of disappointments and traps for the unwary, as a hazardous building site to be negotiated carefully. Every personal calamity—two drops of espresso on a work shirt, failing to hail a taxi in a torrential downpour—is a reminder that one’s movement through the city is constantly stalked by misfortune.

The Colossus of New York predates the current vogue for flâneurs and essays about life in the metropolis. The genre is peopled with novels, essays and tracts that are a tribute to the act of noticing (think of Ivan Vladislavić‘s excellent Portrait with Keys). Whitehead’s book doesn’t glory in the easy material of the everyday, nor does it advocate the kind of smug street-level transcendence that ultimately affirms the city as a closed set of experiences into which one is only invited if one is possessed of sufficient reserves. His caution is sensitive and intelligent, and seems more in tune with the city than the self-consciously clever hot-take essays that have been bodied forth in the years since the book’s first publication. His characters are people like us, not people as we would like to be.

It is no slander, then, to point out that The Colossus of New York reads like a work from the two-thousands. While it is watermarked by the circumstances of its inspiration, it has certainly aged better than many other popular cultural artefacts from that time. Pop music from 2003, for example, sounds a decade older than it is. The book’s age does, however, mean that in 2018 there are lacunae that pothole Whitehead’s description of life in the city. I struggle to find, among Whitehead’s many voices, a trace of the blue and squalid violence that claimed the life of Eric Garner, for instance. Whitehead is not interested in the loutish undercurrent that gave rise to the Giulianis and Trumps, whose ascension seems depressing confirmation of the damned project that is the modern or twentieth-century city.

Where the book better endures is in the quality of its writing. The lyricism of Whitehead’s observations is superbly incantatory. Here, he narrates a tableau in Central Park:

So many people running. Is something chasing them. Yes, something different is chasing each of them and gaining slowly. She feels fit and trim. People remove layers one by one the deeper they get into the park. The sweaters keep falling from their waists no matter how they tie them. The matching strides of the jogging pair give no indication that after she tells her secret he will stop and bend and put his palms to his knees.

See how the observation flares from the mundane to the particular? Anybody who has experienced the awkwardness of shedding warm clothing in public can identify, but just as suddenly as we draw closer something emerges that checks our too-easy identification. Whitehead strikes the balance just right, and it makes for a read whose ability to engross lies in the sustained layering of facts for their own sake, rather than the razzle-dazzle of quick detail.

The problem with this sort of writing, if there is one, is that what is apparently random in fact requires a great deal of writerly precision. Whitehead’s attention is sustained in the early sections, but the effect of all those aperçus begins to blunt in the later sections of the book, where the terse observational style cracks and a more florid kind of writing emerges from the concrete. Here, the book becomes irritatingly hermetic, as though the narrating is being consumed by the very thing it attempts to represent.

Adherents to the cult of the urban believe in the ability of cities to transform people, a view that is wrong-headed and tiresome in its insistence that the city is a rigid environment. The Colossus of New York proposes a fine argument for thinking about the city as pliable: if New York is colossal enough to admit all our human solipsism, then the souls who dwell within it must in some way shape it to be so. They are the walls, not the imprisoned.

- Wamuwi Mbao is an essayist, cultural critic and academic at Stellenbosch University. Follow him on Twitter.