Image: Bob Marley performing at the Zimbabwe Independence celebration, Rufaro Stadium, Harare, 18 April 1980

The new issue of Chimurenga’s pan-African gazette, the Chronic, is out this week. Here we share an excerpt from the new edition, in which Percy Zvomuya delves into the history of reggae in Zimbabwe.

The edition’s title is ‘The Invention of Zimbabwe’, and features writing from Bernard Matambo, Simbarashe Mumera, Ranga Mberi, Marko Phiri, Dwayne Kapula, Netsayi Chigwendere, Chirikure Chirikure and JRB Contributing Editor Panashe Chigumadzi, among others.

14 November 2017. News breaks of a coup d’état underway in Zimbabwe. Tanks, armoured vehicles and military personnel are seen patrolling the capital, Harare. The images send shock waves through social media, traditional broadcast news networks and diplomatic channels. After nearly four decades at the helm, President Robert Gabriel Mugabe, Commander-in-Chief, is set to be deposed by his own army, the Zimbabwean Defence Forces. Before the month is over, Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa, is ushered in as the country’s third president.

The events last November form the backdrop of the latest issue of Chimurenga’s pan-African gazette, the Chronic. The issue sits at the intersection of two research projects that Chimurenga have been developing since 2015. One on new cartographies, which asks the question: what if maps were made by Africans, to understand and make visible their own realities and imaginaries? And a subsidiary project titled ‘Who Killed Kabila?’, where the assassination of DRC President Laurent-Désiré Kabila in 2001 serves as the starting point for an in-depth investigation into power, territory and the creative imagination.

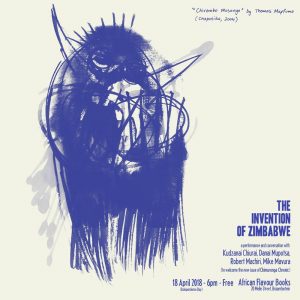

The issue’s launch will take place at African Flavour Books in Braamfontein on Wednesday, 18 April—Zimbabwe’s Independence Day—with artist Kudzanai Chiurai and academic Danai Mupotsa, and contributors Robert Machiri and Mike Tigere Mavura.

Event details

Date: Wednesday 18 April 2018

Time: 6pm

Venue: African Flavour Books, Braamfontein, Johannesburg

More information

To purchase Chronic in print or as a PDF head to Chimurenga’s online shop, or get a copy from your nearest dealer.

Read ‘None But Ourselves’, an excerpt from the latest edition (keep scrolling for the text version):

CHIMURENGA_CHRONIC_excerpt_The_JRBText version:

The history of reggae in Zimbabwe echoes far beyond Bob Marley’s historic concert in the earliest days of the country’s independence. Percy Zvomuya crawls the web of influences that makes up not only the sonic cartography of a revolution fuelled by chimurenga music and reggae, but which are the very groundations of today’s Zimdancehall.’

Sometime in April 1980, a chartered Boeing 707 plane landed at Salisbury’s airport from Gatwick, London. This, in itself, wasn’t unusual, for in the months preceding this charter, with the official end of the war, the airport experienced more air traffic. Even some people who had escaped the country as ‘border jumpers’—most prominent being Robert Mugabe, who arrived on 27 January 1980 in a plane load from Maputo, Mozambique, after five years in exile—were returning to Southern Rhodesia.

Lord Christopher Soames, Winston Churchill’s son-in-law and Southern Rhodesia’s last British governor, had also arrived in the weeks that followed the Lancaster House Agreement of 1979, which had restored the country to the Commonwealth, shredding Ian Smith’s 1965 Unilateral Declaration of Independence, before the elections which would bring majority rule.

On this particular Boeing 707 were lighting and sound equipment, technical crew and Mick Carter, a name which outside of reggae annals doesn’t mean a lot. Mick Carter was a tour promoter for Bob Marley and the Wailers and had arrived in Salisbury in the role of the herald, the prophet who would smooth the path of the coming king, reminiscent of the function John the Baptist played for Jesus Christ. ‘Prepare ye the way of the Lord,’ Isaiah wailed, ‘make straight in the desert a highway for our God.’

The journey into Salisbury, the capital of the formerly renegade state of Southern Rhodesia, which for years had been at war, was a flight into the unknown and Carter thought to arrive in religious garb, an Exodus tour jacket: ‘The people in customs hadn’t a clue what to do, how to deal with us. What got us and everyone through was a huge bag of Bob Marley T-shirts that I had sensibly persuaded Island to give me before I left. These were liberally dispensed all around. And it also helped enormously that I was wearing an Exodus tour jacket, which was my passport to everything.’

Bob Marley would be the first show by an international act since 1972, the year American soul man Percy Sledge performed in Southern Rhodesia, the year in which the guerrilla war against white minority rule began in earnest. (My mother, a fan of Percy Sledge’s music, was at the show and when I was born a few years later, she named me after him.)

Bob Marley and the Wailers arrived on 16 April and, on the morning of 17 April, the day Marley performed at the independence gig, a dry and functional story appeared in The Herald, the country’s biggest daily newspaper: ‘Top Jamaican reggae artists Bob Marley and the Wailers and an entourage of more than 20 arrived in Salisbury from London yesterday.’ The report continued: ‘the band was warmly greeted by a small but enthusiastic crowd of supporters and representatives from the local recording industry.’

It was 1980, the long brutal bush war had ended and rushing in was the future. In this future, even terrorists like Robert Mugabe and their sympathisers like Bob Marley were now welcome. So blinding was the light cast by this tomorrow that no one paid attention to the warning in the song ‘Zimbabwe’:

Every man gotta right to decide his own destiny,

And in this judgement there is no partiality.

So arm in arms, with arms, we’ll fight this little struggle,

‘Cause that’s the only way we can overcome our little trouble.

A couple of stanzas later, Bob Marley sings:

No more internal power struggle;

We come together to overcome the little trouble.

Soon we’ll find out who is the real revolutionary,

‘Cause I don’t want my people to be contrary.

Even though about 50,000 mostly, black people had died, the new nation under the leadership of guerrilla fighter Robert Mugabe was keen to move away from that past. Instead of vengeance and justice, as the thousands of whites who emigrated in the months leading to independence on 18 April 1980 expected, Robert Mugabe signalled national reconciliation: ‘[T]he wrongs of the past must now stand forgiven and forgotten … It could never be a correct justification that because whites oppressed us yesterday when they had power blacks must oppress them today because they have power.’

Bob Marley got to Zimbabwe—the country he had helped sing into being—against the odds. The new government had no money to bring him to perform. But that was a small matter. Bob Marley would pay from his own pocket for the gig, as his gift to the people of Zimbabwe. But even if the new government did have the means to bring the Rastaman to Salisbury, Marley’s namesake was no fan of his music. Robert Mugabe preferred Beethoven, Bing Crosby, Jim Reeves and others, and was no fan of the hairstyle. ‘The men want to sing and don’t go to colleges. Some are dreadlocked,’ he spat, later. In the 1990s, in outrage at the popularity of dreadlocks, Robert Mugabe had urged Zimbabweans to imitate his hairstyle, not Marley’s. So, Mugabe had to be persuaded to invite the Rastaman, whose songs had been listened to with reverence on battery operated wirelesses in the guerrilla camps in Mozambique.

Mugabe’s attitudes towards the music filtered among the elites of Zimbabwe and its judicial and administrative institutions. Dambudzo Marechera, who many mistook for a Rasta man because of his dreadlocks, wrote in Mindblast, his 1984 sketches of the writer as bohème in Harare: ‘I cannot account for the national paranoia about Rastafarians. They invite a lot of Rasta musicians to the main centres of the country yet at the same time, in the whorehouse bars and hotels … in the government corridors and in the squatter settlements—everywhere it seems—the Rasta man and anyone who remotely looks like him is abused verbally, physically, historically, socially, psychologically.’

Zimbabwe’s love for Bob Marley was quite by happenstance. Fred Zindi, a scholar of educational psychology, music critic, and writer, was at the 1980 independence show. ‘We started off, in the 1970s, with Jimmy Cliff (whom Robert Mugabe preferred to Bob Marley), Desmond Dekker and Johnny Nash; those are the artists we knew here until Bob Marley came in 1980,’ he told me at his office at the University of Zimbabwe, where he works as a Professor in the Faculty of Education.

Desmond Dekker? Why Desmond Dekker?

‘He had a hit,’ said Zindi, and then hummed the tune of ‘The Israelites’.

Since my return to Zimbabwe in 2014 after a decade in South Africa, I have been digging in crates, looking for records, trying to trace Zimbabwe’s sonic cartography through what has been discarded in flea markets, dusty SPCA, shops and what people are selling. Desmond Dekker is a rarity. Forty years after the Rhodesians’ affair with his music, there is almost no trace of his records. What you find a lot is Bob Marley. Bob Marley in pristine condition; Bob Marley without sleeves and pockmarked with scratches; Bob Marley with sleeves and in reasonable condition.

‘I met Bob Marley after the show and he said: ‘you must teach them people to love my music, man. The people were standing like stoogies,’ Fred Zindi recalled. And then Bob Marley asked a company man to give Fred Zindi some records, about fifty of them, which he then gave to Mike Mhundwa, a DJ at Radio 3, Zimbabwe Broadcasting Corporation.

In The Herald report a spokesperson for the Wailers said: ‘[W]e will be here until next Wednesday but may have to stay longer. It depends on how the people feel.’ When someone speaks a truth without realising its full spectrum, the Shona say one is speaking as if they have medicine in their mouth.

Bob Marley left Zimbabwe a few days later and would be dead within a year, but his sound remains and can be said to be part of the Zimbabwean psyche and landscape.

Thomas Mapfumo, the co-founder of chimurenga music (with guitarist Jonah Sithole), is also the godfather of Zimdancehall. In the person of Thomas Mapfumo is to be found both reggae and chimurenga music, the sonic with the closest connection to the mbira and the drum, Shona metaphysics and ritual, a way of being criminalised by both church and state since colonial conquest in 1890.

In a Moto interview in August 1990, Thomas Mapfumo was asked: ‘You are known widely as chimurenga king. How do you yourself define chimurenga—is it the rhythm or the message?’

‘I don’t want to hair-split issues. We cannot separate the two (message and beat). Chimurenga music is that traditional beat of mbira, rattles and drums played at important gatherings for our ancestors. So I would not outrightly agree that I am the founder of the beat but rather just [someone] who inherited, improved and perfected it and managed to present it using modern electrical instruments and made it to be liked by more people in these high tech times,’ was Mapfumo’s response. This was 1990, by which time Thomas Mapfumo had released albums including Mabasa (1983), Chimurenga for Justice (1985), Zimbabwe–Mozambique (1988); Varombo kuVarombo (1989), Chamunorwa (1989) and Chimurenga Masterpiece (1990).

Of interest to the story of reggae’s evolution in Zimbabwe is Chimurenga for Justice, a five-track album on which a mainstream Zimbabwean artist first attempted the sound. In that same year, Misty in Roots, a British reggae band that had repatriated to Zimbabwe in 1982, also released an album, Musi–o–tunya, the name the Tonga people, who had lived for hundreds of years by the Zambezi, called the Victoria Falls before it was discovered by David Livingstone. The personnel on that album include Walford Tyson Poko on vocals, Delbert McKay Ngoni also on vocals, Joseph Munya Brown on drums, D Briscoe Tawanda on keyboard, Dennis Augustine Tendai on rhythm guitar, Antony Henry Tsungirai on bass, Crossfield Kaziwai on guitar, and Delvin Tyson Tafadzwa again on vocals. The last names, all Shona, are those the musicians added to their given names after relocation to Zimbabwe.

‘Mugarandega,’ Shona for ‘the person who lives alone’, is Thomas Mapfumo’s sonic riposte of a celebrated motif in literature in Shona and English. Much romanticised in Shona oral traditions is the brooding and solitary figure. This stock character—laconic, ‘without family and friends’, and who prefers the company of his dogs—appears as a spectral presence, first as Samambwa in Waiting for the Rain, Charles Mungoshi’s 1975 classic, and as Mhokoshe in Strife, a 2012 novel by Shimmer Chinodya.

While it is in Zimbabwe’s English literature that this character gained a rugged charm and currency, outlines of this figure were, in fact, first set down on the page in Tambaoga, a 1968 novel about courtly intrigue and ambition by Giles Kuimba. The Shona classic, which partly borrows from Hamlet, features a central character, Tambaoga, the son of a king who has been murdered and who beseeches his son to avenge his death and the usurpation of the throne by his brother. Tambaoga literally means ‘play on your own’ but should be understood to mean ‘keep your own company.’ This name forms a loose association with other Shona phrases, words and names like zai regondo, (the eagle’s lone egg), karikoga (only child) and mbimbindoga (the headstrong person).

On ‘Mugarandega’, Munya Brown—who would later be the mainstay of the legendary Zimbabwean reggae band, Transit—after playing for a while with the popular group Ilanga, was on drums, and Dennis Augustine played keys.

Word reached Fred Zindi that Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited, who were on a tour of Europe, were in London for a series of shows and the recording of a new album. So, Fred Zindi took a bus to Addis Ababa Studios on Harrow Road and on arrival met the chimurenga man, who said to him, ‘I hope you have come to help us. We are trying to record an album which we will call Chimurenga For Justice.’

Zindi has written elsewhere that the band was not used to multi-track recording, preferring to record all instruments at once: ‘Together with the Misty In Roots, we advised Mapfumo to lay down the tracks one-by-one, starting with the drums and bass, until all instruments were recorded. This would bring perfection to the sound as you monitor it track-by-track.’

Tobias Areketa, normally the band’s backing vocalist but who on the day would share the main podium with Thomas Mapfumo, as he had been tasked with doing the Jamaican style chanting, would go into the studio last. ‘Does that mean I have to wait until tomorrow to do my vocals? In Zimbabwe, we all record together at once.’ Zindi explained to him that in the motherland, things were done that way because the record companies wanted to shorten the time bands spent in the studio.

Thomas Mapfumo could have asked Munya Brown or Dennis Augustine—or any of the Misty in Roots crew with a West Indian heritage on the mixing desk—to do the auto-mythologising chants. Instead the chimurenga man asked Tobias Areketa.

This is when the template for Zimdancehall was set down. Tobias Areketa is the harbinger of Potato and the herald of Major E; Tobias Areketa is the ancestor of Winky D.

With love you know from Thomas Mapfumo and the Blacks Unlimited,

the only man to sing all freedom songs during the struggle for Zimbabwe

our motherland you know;

so me say, talk about the man and his beautiful ways

so me say, so me say, so me say,

He is a true man African

He is a true man African

He is a true man African

He is a true man African

I say the man is the Thomas

I say the man is the Thomas

I say the man is the Thomas

I say the man is the Thomas

Dem a put him in jail

What?

Dem a put him in jail

Why?

Dem a put him in jail

Why?

He was singing culture

He was singing culture

He was singing culture

He was singing culture

You know one day them police men, you know, during Smith regime,

They took Thomas Mapfumo, you know,

Because he was singing culture

Culture for the motherland

Zimbabwe

What you say?

I said I love Mr Thomas

I said I love Mr Thomas

I said I love Mr Thomas

I said I love Mr Thomas

He is a true man African

He is a true man African

He is a true man African

He is a true man African.

So let’s love one another

Let’s love one another

Let’s love one another

Let’s love one another

To love the man Mr Thomas

To love the man Mr Thomas

To love the man Mr Thomas

To love the man Mr Thomas

He is a true man African

He is a true man African

He is a true man African

One love you know.

This song, ‘Mugarandega’, from Chimurenga for Justice, was also issued as a maxi single with side two as a dub version. When, in 1988, Thomas Mapfumo released the hit reggae maxi single, ‘Corruption’, in which he decried the pervasiveness of graft in Zimbabwe, it also came with a dub version. Later, on Chimurenga 98, he collaborated with DJ Yuppie Banton on the song, ‘Set the People Free.’ (Yuppie Banton is part of a clutch of DJs that includes Potato and Major E, who mostly chanted in English in faux Jamaican accents, and featured on popular songs from the 1990s.)

On these three songs—’Mugarandega’, Corruption’, and ‘Set the People Free’—Thomas Mapfumo was laying the foundation for the sonic revolution which took shape after 2000, by which time the chimurenga man himself was in Oregon, in a forlorn exile.

A few years ago, from across the Atlantic, Thomas Mapfumo picked a fight with Winky D, by most accounts the star of the Zimdancehall cosmos, which also includes DJs like Toki Vibes, Killer T, Soul Jah Love, Dadza D King Shaddy, Ninja Lipsy and many others. ‘I listen a lot to what the likes of Winky D are singing and my heart bleeds. People like Winky D are destroying Zimbabwean music,’ he stated.

It’s easy to imagine some ardent traditionalists with their faces in a knot when Thomas Mapfumo first ran electricity through traditional war songs like ‘Buka tiende’ and ‘Nyama musango’; or when he penned ‘Hanzvadzi’, a beautiful re-imagination of ‘Nhemamusasa’, the mbira song said to have been laid down after the Shona first settled in (or from) Guruuswa, the mythical place of origin for the Shona.

In the tune ‘Gombwe’, the title track of the album of the same name, Winky D is heeding the cry Thomas Mapfumo himself made in ‘Vanhu Vekwedu’ on Hondo, an album from 1991. ‘Vanhu vekwedu baba havasati vaziva,’ he sang: our people still live in ignorance. The chimurenga man was bemoaning the hegemony of English and American music on national radio and the secondary place local languages occupied in the hierarchy of languages, no doubt because of Robert Mugabe’s own conservative tastes and British pretensions. In that tune, Thomas Mapfumo deftly condensed the polemics of Ngũgĩ’s Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature into just over seven minutes.

On the track ‘Gombwe’, from Winky D’s eighth album which came out in early 2018, the Zimdancehall champion is beginning to explore Shona spirituality in ways I haven’t encountered in the genre before, reminiscent, in fact, of Thomas Mapfumo’s own trajectory. Mapfumo recalls the 1960s and 1970s Rhodesian music scene: ‘There was no consciousness among our artists; they were into copyright music, very few of them wrote their own music at the time because that was a British colony. Everything the radio played was foreign and people had to go for foreign music. Politics was very low at the time. People never thought of that. They never believed in themselves. They thought the white man was superior, he was untouchable, he was like God.’

In ‘Gombwe’, Winky D chants:

Mangoma aya ndabva nawo kunyika dzimu

Anga achitambwa navadzimu

Ndabva ndati ndiwaunze pasi rino

Abva avachemedza samariro

Ndini gombwe remangoma gaffa rinobata matare engoma

(I have brought these tunes from the spirit world/these tunes were being enjoyed by our dead ancestor/I thought to bring them here/they made people cry as if at a funeral/I am a spirit medium and I hold conferences with the dead ancestor about this sound).

In some ways, Thomas Mapfumo and Chiwoniso Maraire, the late chimurenga chanteuse who updated the mbira sound for the R&B generation, belong on the same sonic, spiritual and modernist continuum, geniuses with gourds in hand, which they use to draw deep from the recesses of Shona metaphysics. If Winky D continues on his current trajectory, the master of the Jamaican-Zimbabwean DJ style might one day join this pantheon.

In the 1980s and 1990s, in the ghettos and townships to which Ian Smith and his predecessors had relegated Africans, most working class households owned a hi-fi, some of them with so much wood they looked like coffins. In the aesthetics at play in the manufacture of these appliances, the carpenter seemed to be as important as the electronics engineer.

The radio, it’s no exaggeration to say, occupied a central place in the living room of most homes. It was reminiscent of the huva, the raised mound directly opposite the entrance in the round hut used by many as the kitchen, where we kneel to commune with the ancestors and pour libations and perform other sacraments. Dzangaradzimu, the Shona word for radio, references dzimu, the root for the word for spirit world; dzimudzangara, the inversion of that word is a mythical and ghostly creature, said to be so tall that you can barely see its head.

In the 1980s, before the liberalisation of the command economy, salaries were low and foreign currency was scarce, and it’s no surprise that very few households in the ghettos had televisions. But the radio was everywhere. In the Supersonic and WRS hi-fis, Zimbabwe’s small electronics industry managed to successfully clone the technology to compete with the big boys: Philips, Sony, Aiwa and Telefunken.

Most of these coffin radios played only records, not compact cassette tapes, the technology which towards the late 1980s and early 1990s bridged, in the parlance, materiality and the digital. Whatever the compact cassette lacked in durability, it more than compensated for in portability and, most importantly, by placing into the hands of whoever held it, the power of the recording engineer.

In the early 1990s, as Apartheid fell and men lost their jobs due to the introduction of neoliberal reforms to economy, enterprising Zimbabwean women stepped into the breach. They would venture to South Africa to sell doilies, curios and other wares. On their way back, these women would buy small radios, televisions and groceries for resale in Zimbabwe.

On Thursday and Saturday nights, multitudes of teenagers like myself would sit by these small radios, a blank tape or an ‘original’ inserted, hand hovering over the ‘record’ button, waiting to press ‘record’ on the tune I liked and would love to replay whenever I wanted.

For our generation, Dennis Wilson was one person whose shows were recorded weekly, and endlessly replayed. Dennis Wilson was a Jamaican Briton who had found a job as technician at Posts and Telecommunication Corporation of Zimbabwe, the local telecommunications parastatal. He had started off playing at friends’ parties and had then been invited to play on Radio 3. Back in the United Kingdom, Wilson had been involved in the Downbeat Sound system in Fulham and taken part in the sound system clashes involving Duke Reid Sound, Coxsone, and others.

‘People ask me, why Zimbabwe, and I ask them why not? I don’t know where my ancestors come from. Sometimes the way I feel about [Zimbabwe] it could be here,’ Dennis Wilson told me in 2016.

Once, the DJ went on a visit to the rural home of one of his friends, a descent into the old country resembling the land from which his ancestors had been kidnapped. There, an old man, referencing the old identities which ceased the moment Dennis Wilson’s ancestors got off that boat, asked him about his totem. It had been a few centuries since Dennis Wilson left and he was at a loss. ‘What’s that?’ Dennis Wilson asked back. They would have explained to him how the Shona tribes have an animal, or part of an animal—the heart, say—or a feature from nature (the river, as was the case with Morgan Tsvangirai) that they hold sacred and that they can’t eat, or with which they can’t be familiar.

When Wilson said he didn’t have a totem, the old man offered to adopt him, to embrace him in his own totemic expanse. ‘Don’t worry,’ the elder had said, ‘you can have mine.’ ‘That made me feel so accepted. It meant so much to me,’ Dennis recalls.

In Mbare and Mabvuku, Highfields and Kambuzuma (where Winky D is from), and other ghettos in Harare, in Pfupajena, Umvovo and other ghettos in Chegutu, in Senga and Mkoba in Gweru, and in many other towns and cities, young listeners considered Dennis Wilson’s name as totemic and, twice every week, had a date with him.

When Linton Kwesi Johnson chanted that ‘Inglan is a bitch’, the youths, probably looking at the dusty roads, clogged sewers and cramped conditions they lived in, found the incantations true for them as well. When U-Roy enjoined the massive and crew to dance to ‘King Tubby skank’, it was in the ghetto community halls Ian Smith had built that the youth danced with the most frenzy. And the ‘late night blues’ , Don Carlos voiced so funereally, were at their most real in the ghettos.

Harare’s spatial politics of ghetto and suburb, rich and poor, crowded and spacious, rugged and polished go back to the foundations of the city itself. Today, the division is marked by Samora Machel Avenue (previously, Jameson Avenue, named for Cecil John Rhodes’s right-hand man and lover, Dr Leander Starr Jameson). The city’s division was once signalled by two features: the Kopje, the small mountain in the south which the white settlers had originally chosen to settle in, in September 1890, and Causeway, in the north east, a nondescript piece of land near a stream which had been drained of water.

An observer quoted in Tsuneo Yoshikuni’s African Urban Experiences in Colonial Zimbabwe: A Social History of Harare before 1925 wrote: ‘[T]he two ends have ever since been playing the monotonous game of ‘pull devil, pull baker’ to the infinite loss of Salisbury itself … Causeway and Kopje have become political terms in their little way, and the thing is so notorious that a Bulawayian orator is said to have recently adjured his fellow citizens not to be as Salisbury, a house perpetually divided against itself.’

So today, via a sinuous route, Zimdancehall looms over all; this sound, which grew and found sustenance in the ghettoes, was first voiced in English using borrowed Jamaican accents, which morphed into Shona chants, and now has become the primary tool of Zimbabwe’s reinvention. Urban grooves and hip hop—the sound transmitted in the posh accents shaped in the private schools of the lush northern suburbs of Borrowdale, Greendale, and Mount Pleasant—wilt in the shadow cast by Zimdancehall.

But I am getting ahead of myself. Let me go back to the beginning.

- To read the complete article, buy the Chronic online or from your nearest dealer

3 thoughts on “[The JRB Daily] ‘None But Ourselves’—Percy Zvomuya charts the sonic cartography of a revolution in the new Chimurenga Chronic: ‘The Invention of Zimbabwe’”