Hugh Ramapolo Masekela died in Johannesburg today, at the age of seventy-eight, after a long battle with prostate cancer.

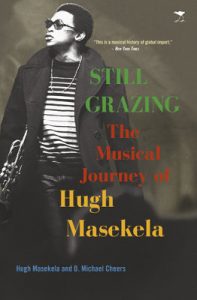

The JRB presents an excerpt from his autobiography Still Grazing, which was published in South Africa in 2017, some thirteen years after it appeared in the United States.

Masekela introduces the new edition as follows:

Still Grazing was published and released in 2004 out of a New York City publishing house.

It has never been published at home. A limited number of copies of this first edition were made available in South Africa, but they sold out quickly and it hasn’t been available for a number of years.

Owing to endless demand by many who could not find the book, we managed to re-secure the rights from New York and we are now able to properly publish Still Grazing in South Africa, with Jacana Media, whose enthusiasm helped make it possible.

This is a story of a man whose life sincerely wish could have been my own—packed with music, travel, outrage, tragedy, history, adventure, learning, spirituality, love, abandon, joy and laughter.

Thank you Jacana Media, colleagues, friends, Pula Twala, Rapelang Leeuw, David Dison, Josh Georgiou, Mabusha Masekela and all who read the book originally and created an environment for its present demand.

All the very best,

Ramapolo Hugh Masekela

Masekela spent the first few years of his life living with his maternal grandmother, Johanna, and younger sister Barbara in Kwa-Guqa Township, Witbank. His grandmother came from akwaNdzundza, the royal clan of the Ndzundzas, an aristocratic house of the Mahlangu Ndebele royal family. She was a strict Lutheran, and considered the gramophone ‘blasphemous’, but still, he writes, in those years: ‘We were surrounded by music, everywhere we went.’

Still Grazing begins:

I grew up in a small town in South Africa named Witbank, a one-street, redneck, right-wing Afrikaner town, surrounded by coal mines and coal trains with endless carriages and coal-packed containers crisscrossing the horizon, pulled by steam engines we called ‘Mankalanyana’, churning smoke up into the air. I remember seeing women in the mornings and at sunset running alongside the coal trains with large tin cups collecting the coal nuggets that fell from the cars. It was a tough town where African miners drank themselves stuporous to blot out memory of the blackness of the mines and the families and lands they’d left behind, often never to see again. But even when the burning coal and dust blackened out the sun, we still had music to sing our sorrow and illuminate our ecstasy. […] It was in those days in Witbank that music first captured my soul, forced me to recognise its power of possession. It hasn’t let go yet.

When he was five or six, Masekela and his sister went to live with their parent in Payneville, near Springs. It was here where his formal training in music began, but he would have to wait a while before finding the instrument he made his own—that would happen ten years later, at St Peter’s Secondary School in Rosettenville, when he first picked up a trumpet.

The following excerpt provides an insight into life on the East Rand in the nineteen-forties; chronicles the emergence of the young Masekela’s musical talent; and paints a portrait of his quietly extraordinary family.

Read an excerpt from Still Grazing:

In 1945 my parents summoned Barbara and me to live with them. They had moved from City Deep to Springs, a mining town thirty miles east of Johannesburg. We were to live in Payneville, a model African township two miles east of the center of town, where my father opened the first milk depot and fruit and vegetable market for the municipality. The town had a coloured section on the south side and a large Indian merchant community on the northern end; a rail fence surrounded the entire settlement. The houses were some of the first built for Africans to have flush toilets. The place had electricity, street lamps, a modern clinic, a nursery school, modern schools for the older children, a shopping center, parks, and a cinema. was very excited about going to live there, not to mention finally being able to live with my parents. It never entered my mind that Payneville would be a passing dream, to be destroyed a few years later by apartheid. very city and town in South Africa had an African township or two like Payneville, until the forced removals of the 1950s. After that, mega-townships like Soweto, with its population of five million, constructed specifically for Africans, became the rule. Coloured and Indians were removed to their own townships.

A self-made man in every sense of the word, my father taught himself architecture, carpentry, landscape design, horticulture, and sculpting. His personal library contained books by Sri Aurobindo, Aldous Huxley, Lin Yutang, Albert Einstein, Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw, William Shakespeare, and Evelyn Waugh, as well as Byron, Keats, Dumas, and Booker T Washington. He was also a self-taught and noted sculptor, and a friend of the famed painter Gerard Sekoto. My father and Sekoto refused to be called native woodcarvers and sketchers, the terms used for African artists. They demanded to be called sculptors and artists just like their white counterparts, who often copied their styles and made huge profits by doing so. My father, Sekoto, and other African artists of their calibre were prevented from gaining recognition for their work. Sekoto, who became known as the father of South African art, went to Paris in 1947, where his works were exhibited in many solo and group shows. My father’s pioneering works were later commissioned by many rich whites in South Africa and exhibited in top galleries around the country. Today a few fortunate African collectors own some of his works.

My mother was a great cook and teacher, and a skilled organiser (she later became president of the National Council of African Women). Although she was a descendant of a Scottish father and a Ndebele mother, and could have opted for the semi-privileged life of a coloured, Pauline chose to be an African community leader. She was fluent in a number of indigenous languages. Their marriage was a difficult union for their awkwardly juxtaposed back-grounds, given the pressures from their relatives and friends and the absurd racial restrictions of South Africa’s social and legislative environment. Some of my father’s relatives openly voiced their disapproval of his choice to marry a coloured woman when so many women from his tribe, church, profession, and social environment were available. Similarly, some of my mother’s relatives never understood why she’d married a black Karanga from the north, when so many eligible light-skinned gentlemen had wanted to marry her. It was a sick state of affairs, which haunted Barbara, Elaine, Sybil, and me throughout our lives. It never mattered how much most of my father’s family grew to respect and love her; there were always those in my father’s family who despised my mother. My sisters and were never considered black enough to be seen as African, nor were we light enough to be totally accepted by our coloured relatives and their friends. Throughout my childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood, many times I’ve been asked the same question: ‘Hugh, tell me really, what are you people, Africans or coloured or in between?’ Angered by the question, I usually tempered my response: ‘We’re just human beings.’ Our parents taught us to be proud of what we were; it has always been easy to explain our origins, those of my grandparents and parents. We learned to trace our family roots as far back as possible. It always amazes people when I tell them that my maternal grandfather was a mining engineer from Scotland.

• • •

In 1946, after attending preschool across the street from our house, I was accepted into St Andrew’s Anglican Primary School, where, because of my high marks, I was immediately promoted to Sub A, the third-year class. One day on my way home from a school trip to gather clay, I was kicking a tennis ball back and forth with my friends as we ran alongside the tar road back to Payneville when a runaway car hit my best friend, Washa, while he was running to get the ball away from the middle of the road. He must have flown over fifty feet through the air before he landed on the grassy side. He never breathed again. Washa was only eight years old. The white man who hit him never stopped, and there was never an arrest. Mr Buitendacht, the township superintendent, under whom my mother worked as a social worker, came to the school and gave a speech warning us not to play in the roads because we were in the way of white peoples’ cars. Even though Payneville was a model township, Springs was very racist and surrounded by other Afrikaner right-wing communities such as Brakpan, Nigel, Benoni, Welgedacht, and Delmas. In 1945 a mining strike was stopped when the army, summoned to shoot black miners, killed scores of them and forced the survivors back to work at gunpoint. This was three years before the apartheid administration took over the government.

Sandwiched between a few minor skirmishes with my playmates and trying to stay out of white folks’ way, we usually rode wild donkeys on Saturdays in the blue gum forest on the southern fringe of Payneville, before going to catch a Gene Autry or another cowboy movie. There was always a weekly serial featuring Dr Fu Manchu, Tarzan, Captain Marvel, or Superman. It was hard to hear from all the cheering, whooping, and laughter. Also, we only spoke Afrikaans, Zulu, and Sotho, and understood very little English. But we still memorised the dialogue and recited along as the film unwound.

It was popular culture that really expanded my English vocabulary. As in the films we saw, most of the words to the songs on the 78-RPM records played on the gramophone were not easy to make sense of, but it didn’t stop me from singing along with the vocalists and scatting along with the instrumentals. My friends and I wore the gramophone out with songs like Louis Armstrong’s ‘I’ll Be Glad When You’re Dead, You Rascal You’, ‘Blueberry Hill’, ‘Rockin’ Chair’, and ‘When It’s Sleepy Time Down South’; Louis Jordan’s ‘Caledonia, Ain’t Nobody Here But Us Chickens’, and ‘Ain’t That Just Like a Woman’; Nat ‘King’ Cole’s ‘Mona Lisa’ and ‘Route 66’; Ella Fitzgerald’s ‘A-Tisket, A-Tasket’,; the Andrews Sisters’ ‘You Call Everybody Darling’, ‘Rum and Coca-Cola’, and ‘Boogie-Woogie Bugle Boy’; Jim Reeves’s ‘Oh My Darling Clementine’; Cab Calloway’s ‘Hi-dee, Hi-dee Ho!’; and Red Foley’s ‘Chattanooga Shoeshine Boy.’

My parents soon realised that I had become inseparable from the gramophone and sang along perfectly with all the American records, as well as those of South African performers, like the Manhattan Brothers’ ‘Jikel’ Emaweni’, ‘Madibina’, and ‘Makanese’; the love ballads of the African Ink Spots, like ‘Ndi, Nje’ and ‘Carolina Wam’; and modernised Xhosa folk songs.

They decided to seek a piano teacher for me, hoping that music lessons would enhance my talents and wean me off the gramophone. During the 1940s there were many piano teachers in the townships, men and women who’d been been taught by missionaries so that they could accompany school choirs and play the organ in church. Many more had been self-taught in the 1920s, when they accompanied vaudeville groups like Emily and Griffiths Motsieloa’s troupe and Wilfred Sentso’s Synco Fans, and learned to read music and write arrangements for small combos and big bands. Township music teachers imparted what little knowledge they had picked up from such groups and from the Salvation Army, police, and military bands, to whatever students they could find. ‘Madevu’ (his nickname referred to his massive beard) was such a pianist, and he was already teaching a couple of girls from the senior grade at St Andrew’s. I became his third and favorite student. After a few months of afternoon lessons, I began to excel.

In a few months’ time I was playing excerpts from Bach, Mozart, Handel, Haydn, Beethoven, and Lizst, along with piano arrangements of nursery rhymes. My teacher’s favorite nursery rhyme was ‘Lavender Blue Dilly-Dilly.’ At the year-end recital, I performed ‘Lavender Blue’ with the school choir to applause from the parents and teachers and endless guffaws from my friends, who all thought it was square white music. It was really embarrassing, but my parents insisted that I continue with the lessons and not pay any attention to my detractors. y mother would say, ‘Don’t mind them, Boy-Boy, they’re just jealous because they can’t play an instrument or sing.’ Wanting to try some-thing new, I yearned to play some boogie-woogie jazz on the piano. Once in a while I would sneak in a snatch of boogie-woogie while practiced my sonata excerpts. One afternoon my teacher caught me and was so furious that he reported me to my parents—he told them this was music for drunkards and harlots, sinners and gangsters, and that it would get in the way of my classical talents. He warned my parents that if he caught me playing boogie-woogie again, he would stop teaching me. Surprisingly, my parents didn’t seem too concerned. They just asked me to try to do my best not to infuriate my teacher and to stay with the programme.