Efemia Chela travels to the dirty and dangerous streets of Mauritius with Ananda Devi’s Eve Out of Her Ruins in The JRB’s Temporary Sojourner series.

Females carry the marks, language and nuances of their culture more than the male. Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.

—Wangechi Mutu

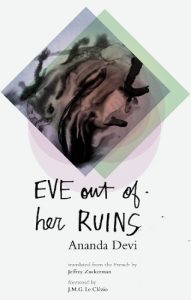

Eve Out of Her Ruins

Eve Out of Her Ruins

Ananda Devi

Deep Vellum Publishing, 2016

Translated from the French by Jeffrey Zuckerman

Island literature is always notable because of its location; islanders are different in a way that is hard to place one’s finger on. Perhaps it’s the unusual distance of their neighbours and their physical closeness to their island’s other inhabitants. Islands have a sense of The Beginning—an elemental return to nature but also new horizons, adventure. Often these two contradictory feelings are in tension, especially for an island like Mauritius, which has been a Dutch, French and British colony. Even earlier, Mauritians traded with the Phoenicians, ancient Greeks and Arabs. The place is a mélange—multicultural, multilingual, multiethnic—and Ananda Devi gives us an insight into what that chaos and flux can come to through the body and mind of Eve.

The Star and Key of the Indian Ocean, as Mauritius is known, loses its shine in Devi’s Eve Out of Her Ruins. Saad, a melancholy poet, influenced by Rimbaud, and one of the book’s four teen narrators, says of the capital:

Port Louis has changed shape; it has grown long teeth.

The city turns its back on us.

We are with him and the book’s other storytellers, Eve, Clélio and Savita, deep in the shadows in Troumaron, whose name could be interpreted as trou marron—‘brown hole’—apt for this poor quartier of Port Louis, the capital city. It’s a place where the local flora is fetid garbage, broken glass, needles and spilt blood. The most ominous neighbourhood landmark is the husk of a sewing factory that went bust. Its decay is an ugly reminder of the discontents of globalisation and the fickleness inherent in its race-to-the-bottom economics. Here wild gangs of boys hang out at night, hormones boiling and fists ready for the destruction of themselves and others—whichever comes first. The parents of Troumaron are resigned (the fathers to alcoholism and petty gambling; the mothers to coma-like silence and domestic servitude), have left a power vacuum. It’s quickly filled by the boys’ deathlust and angst, which provides an underlying menace not dissimilar to A Clockwork Orange‘s.

Also in this hole, on the same dirty and dangerous streets, is Eve, breaching the neighbourhood’s moral boundaries. Notoriously promiscuous, she stands out and is shunned by most of her peers. She faces the quandary that all sex-positive feminists do—is this sex for my pleasure or for my undoing? Can I retain power through, during and using sex? Or, as Eve says in her unadorned, deadpan style, which is consistent throughout the novel:

I am in permanent negotiation. My body is a stop-over. Entire sections have been explored. Over time they blossom with burns and cracks. Everyone leaves some trace, marks his territory. I am seventeen years old and I don’t give a fuck.

Eve is Mauritius, but also very much herself. We enter her mind, full of complex questions about sexuality and poverty. She has a preternatural amount of agency and clarity about her situation for her age. To survive she has divided body and soul. For Saad, badly in love with her, within Eve is the beginning and the end. He wants her to be his end, as he tells us in the very beginning. Saad wants to save her—but Eve would rather save herself. It’s refreshing for a teenage girl to be portrayed as something other than lovelorn and naïve. Eve is not passively slipping towards the point of no return, she is bounding towards it, eyes open and reddened with self-hate, at times listless with despondency or raw with pure nihilism.

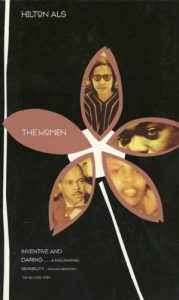

Eve is what Hilton Als in The Women would call a ‘Negress’, a woman who subverts the pity and maudlin sentimentality that people want to force on to her. Speaking about the first Negress he encountered—his mother, who was from the island of Barbados but who moved to New York—he says:

Eve is what Hilton Als in The Women would call a ‘Negress’, a woman who subverts the pity and maudlin sentimentality that people want to force on to her. Speaking about the first Negress he encountered—his mother, who was from the island of Barbados but who moved to New York—he says:

My mother disliked the American penchant for euphemism; she was resolute in making the world confront its definition of her … From my mother I learned the only way the Negress can own herself is her protracted suicide; suffering from imminent death keeps people at a distance.

Trying to hold her back from the edge, trying not to break into her like everyone else but to commune with her, is Eve’s friend Savita. In the mini-class hierarchies entrenched in poor communities her family are slightly above Eve’s: high enough to look down on her and disapprove of the friendship. But perhaps it’s ‘the poetry of women’, the Sapphic overtones of their relationship, and the solace the two girls find in other that repulses them and invokes jealousy in the rest of Troumaron:

The poetry of women is laughter in this lost place, laughter that opens up a small part of paradise so we don’t drown ourselves.

Only Clélio, abandoned by his brother for France, comes off as somewhat two-dimensional—but that could be put down to the vividness of who he’s sharing the pages with and their more compelling plots. His usefulness at the novel’s end, however, forgives his relative dullness.

‘Stereotypes are made for us. We fill them all. We are the champions,’ Saad says, but his creator uses her natural poeticism to make the novel unique and immersive. Each voice is distinct. Devi eschews stereotypes to create an ascent to an unexpected peak of violence that draws the four in—and then blows them up. Her accomplishment as a writer is such that in both English and French (Ève de ses décombres) this a lyrical and rhythmic read:

… the eczema of paint and tar beneath our feet …

Summer numbs us at first, before the heat revives the landfill’s call and stirs anew our shadows, our sleepy dregs …

… her hair like the foamy night …

The book sings—sometimes a ballad, sometimes a fleeting cry of joy, but Eve Out of Her Ruins always sings.

- Temporary Sojourner is a series of articles by Contributing Editor Efemia Chela on the best fiction from around the African continent. Reading is the cheapest way to travel, after all. This is the third article in the series, which draws its name from the eponymous collection of short stories, first published in 1989 and reprinted in 2011, by Editorial Advisory Panel member Tony Eprile.