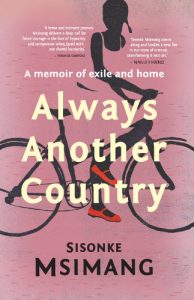

Sisonke Msimang, who grew up in exile, describes her first visit to South Africa in December 1990, the year Nelson Mandela was released, in an exclusive excerpt from her new book Always Another Country.

Always Another Country

Always Another Country

Sisonke Msimang

Jonathan Ball Publishers, 2017

The return to South Africa

In February 1990, Nelson Mandela is freed. I am sixteen years old, and I am staying with Uncle Stan and Aunty Angela in Nairobi. Dumi and Lindi are studying in America, and Mummy and Baba and the girls have moved to Ethiopia because Baba has yet another job that requires us to move.

Uncle and Aunty and I sit in front of the TV as CNN teleports South Africa into the room. Nelson and Winnie Mandela are walking hand in hand. His fist is raised in the air and she is beautiful and they seem like strangers to each other. We are crying. Aunty keeps shaking her head in disbelief. Uncle keeps standing up and pretending he is not crying. I stay still, transfixed.

I watch the scene on a loop, combing the background for details. I am looking at the sky and the faces in the crowd and what every-one is wearing. I am imagining the smell of the place and wondering whether it is cold. I am trying to imagine myself into the moment. I watch the old man who is walking slowly and stiffly. This is not the Mandela of the T-shirts. This man is so lean; so old. He is relying on his wife more than he ought to. I watch and I watch and I watch, as though somehow the screen might suck me in.

Baba is cagey about going back. He wants to be sure that the unbanning of all political organisations is real, that this is not a trap. But it will be safe for me: I am a child who has never been linked to any terrorist activity and I have a foreign passport. Uncle Stan is coming back as an academic and it is different for him too. He is offered a job at the University of Natal. He accepts and in December that year as the Sangweni family boards a flight to Johannesburg I am with them. We are headed home.

* * *

Jan Smuts Airport is bathed in a dirty fluorescent light, the kind that makes even perfect skin look pitted. The ceilings are low and there is too much brown brick. The airport is a fascist fortress, designed to withstand attack. The interlocking buildings all have small windows—air holes rather than features really. Jan Smuts is modern if you consider the 1970s modern. I do not.

Our passports are stamped by a row of stern-looking immigration officials who ask what we are doing here. Each of them seems to have a moustache and I have an urge to giggle, but I sense this would irritate them. I say I am here to visit family and they ask no further questions. Mandela has guaranteed us safe entry into South Africa, even though apartheid is still alive. They do not smile or welcome us but they let us in.

Outside, my cousins Slumko and Mandisa are waiting. Slumko is the glamorous big brother fifteen years older than me so already a grown man. Mandi is his excitable younger sister, only five years my senior, which is old enough to be far cooler. They grew up in neighbouring Swaziland so they are already connected to what is happening ‘inside’.

Slumko studied in America and moved to Johannesburg a few weeks before Mandela was released. He is massive—two metres tall—and good-looking, and everywhere we go people look at him as though he is a superstar. The white women’s eyes linger the longest. When you meet their gaze and smile because you have noticed them noticing him, they seem surprised at themselves, and embarrassed.

Mandi still lives in Swaziland but she is in Joburg a lot because that is where all the action is, and her personality is too big for sleepy Swaziland. We hear her high-pitched squealing before we see her face. She too is long and lean and, like her brother, she turns heads. She preens and purrs and dresses so that any woman within ten metres walks in her shadow. In the week-long sojourn, Lindi and I will be pale grey egrets to her peacock hues.

But now we hug noisily and dramatically. This is our first trip home and we sense that our actions will be scrutinised. We are on a stage, unsure exactly who will be watching but knowing nonetheless that we will draw attention. We want to be worthy of the surveillance.

We don’t all fit into Slumko’s sleek German car so we split up. Lindi and Dumi and I take the shuttle to the airport Holiday Inn while Uncle and Aunty get into Slumko’s car. We are only in Joburg for a night. In the morning we will head off to Pietermaritzburg. We are in South Africa to begin the process of settling Uncle at the University of Natal and have combined this with the business of meeting our family members for the first time.

Uncle and Aunty go to sleep. They are tired and want to stay in, so they release us. Go and see Joburg, they say, and we do. We have only seen the city through Brenda Fassie videos smuggled out by comrades. In all her songs Brenda is glamorous in a way that makes her seem beautiful even though she is not. In the videos, her city looks big and fast and so shiny it cannot possibly be real. I have never seen an African city whose buildings are so heavily concentrated.

Slumko says he knows exactly where to take us so we turn up the music and ease into the darkness and then hit the highway in search of trouble.

Hillbrow is awash with neon and urine and when I roll the windows down there is the faint smell of vomit. Hillbrow is not yet seedy, though it is slouching towards disrepute; its dodginess is hidden around the corner, just out of view. Cars crawl along Kotze Street, flanked by long-limbed black girls who’ve come in search of fresh starts. Many of them are jittery. Between the police and the coke it is hard for them to stay still. Paunchy white men leer—here to satisfy a hunger apartheid’s laws cannot sate.

We end up at a café where everyone looks chic and is sitting on Parisian-style sidewalk chairs. It is busy inside so we sit outside in the warm evening. The city of gold glitters around us like a madam’s box of jewels. Somewhere someone is smoking weed and the smell of it eases us somehow and our laughter is more pronounced, our sense of our own bodies grows, our smiles are punctuation marks, our sighs languorous and revelatory. This country is already ours and we know it so we are basking in one of those moments kissed by the gods: it sparkles and shines and so do we. We are young and freedom is in front of us and heartbreak and pain are yesterday’s heroes.

A man appears. It is as though he was sent to remind us that the world is made not only for the young and beautiful but also for the old and the grey. He is shrunken and mottled so that he looks like something discarded, a paper bag lying on the side of the road or a can crushed on the pavement. But he is not nothing. He is a man.

At first we only notice him moving at the edge of the frame but soon he is centre stage and rising. He opens his mouth and sings, ‘Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa, men have named you. You’re so like the lady with the mystic smile.’ He croons as though he were born to the stage. ‘Do you smile to tempt a lover, Mona Lisa?’ he continues and a silence settles on us. ‘Or is this your way to hide a broken heart?’ His voice is like velvet but he is singing for his supper. He is literally holding a cup in his hand and we are singing along because he has transformed into Nat King Cole in a dinner jacket and a tie and we are transported into a world his voice has made and in it there is no rancour, only the beautiful ones who have been born for this black and beautiful moment.

Without warning or provocation a waitress with a screaming gash of a mouth is shouting at our debonair crooner. She is standing in front of him—‘Get out of here’—and before he can respond she pours water on him and he is humiliated and cowering in front of her, shivering like a dog.

Ah! Here it is, finally: the moment we anticipated as we packed our bags in Nairobi. We landed in South Africa prepared for this confrontation. Truth be told, our lives in exile as the children of revolutionaries were one long rehearsal for this scene.

Here is the villain and she is barely a woman, still a child really, smashing the dignity of a man who could have been our father.

And he is taking it. ‘Sorry, please, I’m sorry, forgive me, I’m only looking for bread.’ His voice is no longer velvet. Now it is cracked stones, gravelly and ruined by drink. But still each word is enunciated perfectly as though he were educated at Eton and the contrast between what he once was and where he kneels now, wet and trembling on the street, should be too much for anyone to bear.

We are up on our feet and Slumko is roaring and Mandi is hissing and I am shouting and Lindi is stabbing her finger into the waitress’s face and the girl who is almost a woman is white as a sheet and backing slowly inside, edging her way towards the safety of the restaurant. We are following her and we are seething and rage boils in our veins and we are so outraged that we forget the old man. We forget to ask if he is okay. Instead, we give the perpetrator our full attention.

‘What are you doing?’ Slumko thunders. ‘That man is old enough to be your father!’

‘You have no respect. What kind of behaviour is that?’ Mandi chimes in.

‘Where is your manager?’ says Slumko. ‘This is simply not on.’

The waitress gulps. She looks shaken but she is defiant. ‘You don’t work here,’ she says. ‘Every day he’s here. Every day asking, begging, bothering the customers.’

‘We are customers,’ Slumko retorts. ‘We are paying customers and we didn’t complain.’ Then it is her turn to look towards the ground, chastened.

I go in for the kill. ‘You’re racist. That’s your problem. You’re racist and you think you can talk to him any way you like because he’s black.’ My objective is to maim, not to reconcile or elicit under-standing.

The waitress’s eyes snap into focus and she wants to cry but she is stubborn and entitled to express herself and she has never ever been spoken to like this by black people and she cannot allow this travesty to unfold like this. ‘Don’t tell me I’m a racist. You foreigners think you know everything about this country but you know nothing. This isn’t America, this is South Africa.’

The word ‘racist’ is like a dog whistle and the other patrons are now paying attention. A pack has formed.

A white man at a nearby table pipes up, ‘She’s right. I come here all the time, that old man is a pest. Tell me something? Have you ever been here before?’ he asks, looking me dead in the eye. ‘Have you ever walked into this place before tonight? Because if you had, you would know, we are all nice here. There’s no racialism. This one here’—he motions at the waitress—‘is just doing her job.’

The kinship of skin is deep.

They think we are strangers; they have assumed we are black Americans and this makes us even angrier, so Lindi says in her British accent, ‘You think we’re from America? You think that because we speak English we aren’t from here? Don’t try those tricks, you have nothing to teach us about our own country.’

An old white woman, who looks as though she may not have a place where she can lay her head every night, wanders into the conversation. She is thinner than an old woman should be, so thin she cannot have children to feed her. She takes us all in and hisses in our general direction, ‘Don’t bother about them. It’s obviously a case of bad breeding.’

Mandi loses it. ‘Breeding is for horses,’ she says in her high-pitched voice. ‘If you haven’t noticed, there are no animals here, just black people who happen to be human.’

The restaurant manager makes an entrance. He introduces himself and tries to assert an authority we do not respect. We don’t care about restaurant decorum. We have flown across the length of a continent and travelled decades in anticipation of this moment. A supervisor will not stop this collision course with a confrontation we see as our birthright. We are here to confront the apartheid whites whose boots have been on our necks. We are unruly and ungovernable. We have not been exiles only to return and capitulate with the politeness expected of us by unrepentant whites. We have found the racism our parents fled and we intend to mine it for all it is worth.

We respect the manager only insofar as he is capable of moving our agenda forward. So we demand that he instruct his waitress to apologise.

She refuses.

We insist.

He prevaricates, does not know what to do with blacks like us.

We smell blood.

‘What are you waiting for? We have demanded an apology for the racist actions of your employee and you seem to be thinking. Don’t you know that the customer is always right? Where exactly did you get your training?’

We sneer.

He stutters something incoherent.

‘Listen, this is not about us,’ Slumko says. ‘We don’t give a damn if she apologises to us or not. An old man has been offended here and he is the one she should be saying sorry to. Not us. She says it, and we let it go. She doesn’t, and you’ll be hearing about this for a long time to come. You have no idea what kind of connections we have.’

We are steeped in the rules of middle-class combat and far more cosmopolitan than he can imagine. It has been many years since we last suffered any kind of indignity, yet we know all about the moral high ground. We have been raised to fight on behalf of those who cannot speak for themselves. We have the articulate outrage of the entitled and we have the advantage of surprise. We are brown and that should not mean we are afraid or uneducated or polite. We are none of these.

The waitress senses she has been outwitted. She is confused—she had not known that a group of uppity black Americans would sabotage her shift. How could she have known? She looks at Slumko with his hulking muscles and his movie-star looks, and then at Lindi and Mandi and me—tall and elegant in our jeans and our high-heel sandals and made-up eyes—and she knows she must relent.

Her manager—frightened and equally confused—accompanies us back outside. The rest of the café clientele looks on. They have chosen sides—a small number are with us but the bulk are shocked by our cheek. Even here, in the most liberal of Johannesburg’s streets, no one has really begun to imagine the future. And yet here it is: brazen and unrelenting and demanding. Everything is tense and frozen and the neon street no longer looks glamorous. We are in a seedy part of town and the whites here are only sitting next to blacks because their choices are constrained.

He is gone. The old Bojangles has vanished and all our remonstrations have come to naught.

The waitress looks at us triumphantly, as if to say, ‘So much for that.’ But she quickly rearranges her face when she realises that, even though the victim we were championing has slunk off, we still hold the balance of power. We are angrier and more articulate than she is, and his absence does not change that, although it does sting. He is not there to celebrate our eloquence and bravery; he has gone somewhere to find the meal he was seeking. He has disavowed us.

‘I’m sorry,’ says the manager. He avoids eye contact with the rest of us, as though the fight was caused by too much oestrogen. Then he gives Slumko a look that says, ‘Man to man, let’s let this go now.’ He continues, still talking to our fearless leader. ‘I think we have learnt a lesson today and we will make sure it never happens again.’ He looks Slumko in the eye as though he hopes that sense will prevail. Slumko is seduced: the inclusiveness of the male gaze is so hard to resist.

‘It’s fine, man, it’s okay. We understand.’

The waitress is released and she scampers away. We stare at her back as she retreats. The manager walks us to our car, intent on making sure we leave his establishment and don’t cause any more trouble.

‘Next time you are here, please swing by, it will be a free drink. On us!’ says the manager to Slumko. The rest of us are invisible. We brought the trouble and now we are being ushered into the car. Slumko is the man of the hour because there is nothing else the manager can hold onto. We are not ordinary blacks he can threaten; we are loud-mouthed women led by a man who surely must be open to some sort of reason.

Slumko gets behind the wheel and the rest of us pile into the car. The car impresses the manager. In years to come he will see many more blacks like us but on this night we are singular and so his disquiet grows.

He reaches in to shake Slumko’s hand and then we pull off. After a few minutes of silence we burst into laughter. We retell the story of our heroism, we cheer one another on for standing up to the rabid racists and we dub Slumko the sell-out for forging a pact to bundle us out of there without causing further chaos. We laugh and we feel full although we haven’t eaten.

We will dine on the story for years to come and over time we will end the story with Mandi’s words as the punchline: ‘Breeding is for horses. We. Are. Human.’ Sometimes when we are together we will say the line in unison, cackling and giving one another high fives at this part, gloating about how clever we all were.

The old man and his vanishing act will become less and less important. We will forget whether he was singing ‘Mona Lisa’ or ‘Mr Bojangles’. The story we will tell in the weeks and then years after this scene will be about our own chutzpah. It will be about our encounter with the racism we have been told about our whole lives.

- Sisonke Msimang is a writer and activist who works on race, gender, democracy and politics. Her memoir, Always Another Country, was published by Jonathan Ball Publishers in October 2017.