In the late nineteen-seventies, James Baldwin encountered an ‘extraordinary and illuminating’ Rhodesian book, which influenced his thought around black rage and white fear.

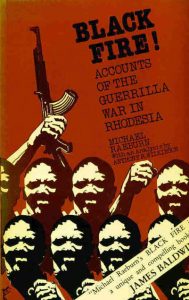

Black Fire! Accounts of the Guerrilla War in Rhodesia

Michael Raeburn

Julian Friedmann Publishers, 1978

1.

Given the rich relationships enjoyed by African Americans and black South Africans—Langston Hughes with Es’kia Mphahlele, Bloke Modisane and others; Duke Ellington with Abdullah Ibrahim and Sathima Bea Benjamin; Stokely Carmichael and Miriam Makeba; James Baldwin and Lewis Nkosi; WEB Du Bois and Sol Plaatje; and so on—the absence of similar friendships between African Americans and black Rhodesians is bewildering.

Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) is just across the Limpopo River from South Africa; both countries were settler enclaves, and in Cecil John Rhodes the two have a common ancestor, which explains to a large degree the toxic racial dynamics weighing down on each. Of course, South Africa’s publishing and music industry is richer and older, so perhaps it’s only natural that the communion between two of the most significant black populations on Earth was restrained to the respective, matching, cultural marketplaces.

When there was communion between Southern Rhodesia (which from now on I’ll refer to as Rhodesia) and the United States of America, it expressed itself in rather bizarre and reactionary ways. James Earl Ray, Martin Luther King’s assassin, was arrested in London as he was fleeing to Rhodesia. In 1967, a year before he murdered the civil rights leader, Ray considered relocating to Salisbury (now Harare), where Ian Smith, he wrote in a letter to the American-Southern Africa Council in Washington, DC, ‘was doing a good job’.

In Hellhound on His Trail: The Stalking of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the International Hunt for His Assassin, Hampton Sides writes that of Ray that ‘the idea of Rhodesia burned in his imagination, the promise of sanctuary and refuge, the possibility of living in a society where people understood’.

Rhodesia, then, was a renegade republic ruled by Smith who, to forestall majority rule, had unilaterally declared independence from Britain in 1965. By denying the black majority a vote and stripping them of rights in their own land, Smith made sure that only an armed solution would break the impasse. Robert Mugabe—whom history will judge as a toy revolutionary and who would create a black elite system resembling Smith’s—is wont to say, ‘we fought for this country’ and on that point the ninety-three-year-old veteran dictator is right, with emphasis on fought. We can trace Mugabe, the cyclical tradition of violence, and some of the grotesque contortions of nationalism that have been played out since independence in 1980 right back to the decision by white Rhodesians to establish a white state.

The publication of Michael Raeburn’s Black Fire! Accounts of the Guerrilla War in Zimbabwe resulted, if for a moment, in a radical departure from the reactionary relationship of old between the USA and Rhodesia. I had been aware for some time of Black Fire!, five atmospheric, fictionalised accounts of historical moments from the armed struggle against Smith’s settler government, by Raeburn, a Zimbabwean writer and filmmaker. (Raeburn was at pains to refer to his sources, including court records, newspaper reports, interviews with the protagonists, and so on, so as to place his work within the ambit of history, but simultaneously deployed fictive techniques to tell the stories as vividly as possible.) Going through the contents, ‘The Crocodile Gang’ tells of a group of guerrillas who made incursions into Rhodesia for the purposes of sabotage and were involved in the killing of a white man—perhaps the first white casualty of the war; ‘Refusal’ is about a guerrilla who turns from believer to agnostic, in some ways anticipating the contradictions of the nationalist struggle; ‘The Spirit’ is about a guerrilla who hibernates in Rhodesia while he grapples with African spirituality and metaphysics and the consequences of war; ‘On the Move’ is, again, about guerrilla incursions into Matabeleland, in southwestern Zimbabwe, where the military wing of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu), Zipra, sometimes partnered with South Africa’s uMkhonto weSizwe resistance soldiers; and finally, ‘Black Fire’, the title story, marks a departure from the random acts of banditry we witness in ‘The Crocodile Gang’, with the protagonists moving towards the adoption of more sophisticated guerrilla warfare tactics.

The publication of Michael Raeburn’s Black Fire! Accounts of the Guerrilla War in Zimbabwe resulted, if for a moment, in a radical departure from the reactionary relationship of old between the USA and Rhodesia. I had been aware for some time of Black Fire!, five atmospheric, fictionalised accounts of historical moments from the armed struggle against Smith’s settler government, by Raeburn, a Zimbabwean writer and filmmaker. (Raeburn was at pains to refer to his sources, including court records, newspaper reports, interviews with the protagonists, and so on, so as to place his work within the ambit of history, but simultaneously deployed fictive techniques to tell the stories as vividly as possible.) Going through the contents, ‘The Crocodile Gang’ tells of a group of guerrillas who made incursions into Rhodesia for the purposes of sabotage and were involved in the killing of a white man—perhaps the first white casualty of the war; ‘Refusal’ is about a guerrilla who turns from believer to agnostic, in some ways anticipating the contradictions of the nationalist struggle; ‘The Spirit’ is about a guerrilla who hibernates in Rhodesia while he grapples with African spirituality and metaphysics and the consequences of war; ‘On the Move’ is, again, about guerrilla incursions into Matabeleland, in southwestern Zimbabwe, where the military wing of the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (Zapu), Zipra, sometimes partnered with South Africa’s uMkhonto weSizwe resistance soldiers; and finally, ‘Black Fire’, the title story, marks a departure from the random acts of banditry we witness in ‘The Crocodile Gang’, with the protagonists moving towards the adoption of more sophisticated guerrilla warfare tactics.

I suppose what first drew me to Black Fire! was the fact that Baldwin wrote the blurb when it first came out in 1977. One day a couple of months ago, while I was going through papers belonging to German-South African writer and journalist Ruth Weiss, housed at the Basler Afrika Bibliographien in Basel, Switzerland, I saw a 1978 story in the Guardian whose headline caught my attention: ‘Baldwin helps to launch book about Rhodesia’. So there was a US-Rhodesia link after all—even though Raeburn, who was born in Egypt, grew up in Rhodesia, and studied in Britain and France, isn’t black.

Baldwin had seen advance copies of Black Fire! and decided not only to write the blurb and introduction to the book, as well as a review for The Times but, on its launch, the American even travelled from his base in the South of France to Hampstead, London. Baldwin told the Guardian:

For me it is an extraordinary and illuminating document. It puts over a real feeling about the country, and what seemed from afar to be a simple battle is revealed as something exceedingly complex. I got a sense of the land, and of the spirit which moves the people. In places it is a very depressing book, but it also gives the impression of the energy and the struggle behind the struggle—and it is the energy which emerges that prevents the book from being despairing.

Like many Americans, Baldwin didn’t know a lot about Rhodesia, but he recognised, as noted in a 1968 Esquire interview, that ‘Black people in this country [the USA] are tied to subjugated people everywhere in the world.’ Because of his relative ignorance of the Rhodesian context, the author of Go Tell It On The Mountain was reluctant to make predictions about the war going on there and how it would pan out:

It would be presumptuous of me to dare say what will happen there. I have my accumulation of ignorance, my curiosity, my concern and my own political convictions—but I just don’t know enough about it all. But I do know that the efforts of the guerrillas, despite the terrible price they pay, has had an effect on the consciousness of victims of the horror that is Rhodesia, and that changes their world for ever. There is no turning back after that.

When asked about his moniker, ‘the angry man of American black literature’, Baldwin said, ‘I’m still angry. There’s a lot to be angry about. But I feel the anger in a different way. Colder, quieter perhaps, but still angry.’

2.

By the time Baldwin got involved with Rhodesia, The Fire Next Time, his book of essays described by Jamaica Kincaid as ‘incendiary’, had been out for some fifteen years. (It’s difficult not to notice that the word ‘fire’ is common to both Baldwin and Raeburn’s books.) While the specifics of the Rhodesian colonial situation might have been beyond Baldwin’s immediate grasp, he knew the rough outlines of the Smith-headed white supremacist dictatorship rather too well: after all, back in America, he had lived under something similar.

Midway through The Fire Next Time, in a piece about the place of violence in political struggle, Baldwin argued:

When Malcolm X, who is considered the movement’s [Nation of Islam] second-in-command, and heir apparent, points out that the cry of ‘violence’ was not raised, for example, when the Israelis fought to gain Israel, and, indeed, is raised only when black men indicate that they will fight for their rights, he is speaking the truth. The conquests of England, every single one of them bloody, are part of what Americans have in mind when they speak of England’s glory. In the United States, violence and heroism have been made synonymous except when it comes to blacks, and the only way to defeat Malcolm’s point is concede it and then ask oneself why this is.

A few lines later, Baldwin answered this question: ‘The real reason that non-violence is considered to be a virtue in Negroes—I am not speaking now of its racial value, another matter altogether—is that white men do not want their lives, their self image, or their property threatened.’

‘The Crocodile Gang’, the first piece in Black Fire!, fits snugly into the idea of why violence is not celebrated when the machete, the AK-47 or the Molotov cocktail is in black hands. The piece reverberates with screams and death rattles at the same time that it drips with blood—blood shed by Ian Smith and blood spilled by the nationalist guerrillas. Action in the piece begins at Salisbury prison with the execution of three Africans, two of whom had been sentenced under the Law and Order Maintenance Act of 1960—the law that took away whatever political agency black people still had and criminalised just about every political act.

This act of state terror is, I guess, what Mugabe was referring to when in an August 2001 speech about Mbuya Nehanda, a hero of the 1896-7 war against white settlers, and other warriors killed by colonialists, he said:

[Mbuya Nehanda] died at the hands of a British hangman, at the hand of a representative of the Free World, and died for resisting violent imperial encroachment. The thud of her lifeless body would not be the last one to be heard on this land, as many more lives would be executed in the walls of the British gaol, in battles of resistance and in villages, all in the name of British law and justice.

Introducing the ‘crocodile gang’, a much-mythologised guerrilla unit that signaled the advent of a new, more violent phase in the nationalist struggle, Raeburn writes that ‘five men sat in hiding, watching the occasional car or truck pass’. It is as they wait that they hear the hum of a car driven by Pieter Oberholtzer, an Afrikaans factory worker, accompanied by his wife, Johanna, and their three-year-old daughter. Oberholtzer is stabbed in the chest before he manages to shoot at the guerrillas, who also throw Molotov cocktails at his car. This indiscriminate act of violence against a white man, who is neither a soldier nor a cop, marks the beginning to the real war, the consequences of which we have not yet begun to contemplate, even thirty-seven years after independence. By the time the war ended, fifty-thousand people, mostly black Zimbabweans, had died.

3.

In his review of Black Fire!, Baldwin wrote in terms and accents that have become familiar in the field now known as Black Studies:

The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the colour line, said the great black American scholar and writer WEB Du Bois in 1903. No one paid much attention to these words then; and only those who must pay, pay very much attention to these words now.

Baldwin also noted that:

The Rhodesian problem, which is not new, is only now beginning to paralyse the attention of the West. This is not, alas, due to black suffering in the region, it is not even because of black rage: Rhodesia paralyses the attention of the West because of white fear. Disturbing sporadic reports have filtered through for years, but until recently nothing seemed really menaced; that is, nothing white seemed menaced. Now time has blown a whistle, and time is running out.

The act that induced John, one of the crocodile guerrillas, to kill Oberholtzer is somewhat similar to an incident in Baldwin’s essay ‘Notes of a Native Son’, from his book of essays of the same name. John had worked as a waiter in a white, Greek-owned restaurant in Salisbury, a joint frequented by young, rowdy whites. In this restaurant also worked Josiah, an old, creaking black man who was the target of the white boys’ jokes—boys who wanted to show off to young white women and prove they were not ‘sissies’ or ‘softies’:

‘Hey you, madala,’ called out one of the boys to Josiah, rudely addressing him as ‘old man’ in kitchen-kaffir. ‘Bring me a coke and six straws.’

The boys all laughed. Josiah, at the time, was struggling to wade through the crowd with a tray of coffees. As he passed their table, one of the boys grabbed the tail of his white uniform: ‘Those coffees will do fine,’ he said.

‘Hey, put them down, boy,’ said another.

Hey, you! Are you deaf or something,’ shouted another.

But Josiah didn’t change his expression. He had one of those calm, still faces that had been walled up by a lifetime of humiliation and servitude so that none of the terrible things going on around him could through to the quiet of his inner world.

I was born a few years before independence and so, in many ways, I am a ‘born free’, but even I have seen this figure in independent Zimbabwe: stooping, forbearing, always on the point of breaking into a reassuring smile. As a black Rhodesian, John must also have seen this tormented figure countless times before.

The white boy keeps at it, goading Josiah, resulting in the tray he holds tipping, everything spilling on the floor. An enraged John sees something else in the events: ‘These people needed to be vicious to be funny.’ In an act that unites John with black resistance over the centuries, here in Africa and in the Americas, he goes for the white boy’s throat and starts shaking him. For this act John is sentenced to a year in prison.

When Baldwin read ‘The Crocodile Gang’ it’s quite possible he remembered his own experiences at a New Jersey restaurant frequented by Princeton students, where he would wait to order a hamburger and coffee. He writes that ‘it was always an extraordinarily long time before anything was set before me’. But it is not until the fourth time he visited that he learnt that nothing had ever been actually set before him, for that establishment didn’t serve black people: ‘I had simply picked something up’.

Baldwin’s experience in that restaurant was replicated everywhere, all over New Jersey, in bars and restaurants where he ‘was always being forced to leave, silently, or with mutual imprecations.’ He writes:

That year in Jersey lives in my mind as though it were the year during which, having an unsuspected predilection for it, I first contracted some dread, chronic disease, the unfailing symptom of which is a kind of blind fever, a pounding in the skull and fire in the bowels. Once this disease is contracted, one can never be really carefree again, for the fever, without an instant’s warning, can recur at any moment.

The high point of this fever was on Baldwin’s last night in New Jersey when, in the company of a friend, he entered a whites-only restaurant and promptly sat at a table for two.

I do not know how long I waited and I rather wonder, until today, what I could possibly have looked like. Whatever I looked like, I frightened the waitress who shortly appeared, and the moment she appeared all of my fury flowed toward her. I hated her for her white face, and for her great, astounded, frightened eyes. I felt that if she found a black man so frightening I would make her fright worthwhile.

The waitress repeated the refrain, ‘we don’t serve Negroes here’, setting off the bells that signal the centuries-long nightmare of being black, at which point Baldwin threw a half-full mug of water at her, missing the target and shattering a mirror. He fled from the restaurant, with police and others in pursuit. Later that night, as he reflected on the incident, two facts troubled him: ‘one was that I could have been murdered. But the other was that I had been ready to commit murder.’

When Baldwin argued for the justness of the struggle in Rhodesia, he did so using symbols Americans could understand:

Michael Raeburn’s book consists of dramatic accounts from Rhodesia of the personal experiences of people we hear so much about today: the terrorist, the guerrilla. Mountains of pious prose are produced every day concerning these dreadful creatures. The father of my country, God bless him, a certain Mr George Washington, was not very highly regarded in England, and the rabble he led, at that hour, would have received unanimously unfavourable press. The French revolution terrified everyone in Europe, and was, then, considered to be the end of the civilized world …

He continues: ‘but, however difficult this recognition may be, it is important to recognise that these tremendous human upheavals are produced by human need.’

The need, the right, for every individual—every black man and every black woman—to determine their destiny demanded a great upheaval, and so it is that thousands died, that thousands more lie in unmarked, nameless graves, and that thousands of anonymous people paid unquantifiable sacrifices. That a nationalist relic, ninety-three years old, sits astride the dreams and hopes of many doesn’t mean the sacrifices shouldn’t have been made.

And the nightmare of nationalism over which the ninety-three-year-old presides is something that Baldwin, being the prophet he was and through bitter experience, had already gestured at in The Fire Next Time in 1963—the very year Zanu PF was formed:

We should certainly know by now that it is one thing to overthrow a dictator or repel an invader and quite another thing really to achieve a revolution. Time and time and time again, the people discover that they have merely betrayed themselves into the hands of yet another Pharaoh, who, since he was necessary to put the broken country together, will not let them go.

In this, we see that even before Baldwin was in Rhodesia he was already in Rhodesia, being a prophet and, eyes wide open, a witness.

- Percy Zvomuya is a writer and football fan. Earlier this year he was the recipient of a Carl Schlettwein Foundation Grant, which enabled him to go through the Ruth Weiss archive housed at the Basler Afrika Bibliographien, Basel.

Good piece.

Keep writing, keep breathing words

The cleansing business accomplishes cleaning of spaces of numerous dimensions as well as arrangements.

The business’s specialists provide cleaning up with the help of contemporary innovations, have special equipment, and also have certified cleaning agents in their collection. Along with the above benefits, wines supply: positive prices; cleaning in a short time; high quality outcomes; more than 100 positive evaluations. Cleaning up workplaces will aid keep your work environment in order for the most effective work. Any firm is extremely important environment in the group. Cleaning up services that can be gotten cheaply currently can assist to organize it as well as give a comfy area for labor.

If essential, we leave cleaning up the kitchen 2-3 hrs after putting the order. You get cleaning up immediately.

We offer professional maids ny for exclusive clients. Utilizing European equipment as well as accredited tools, we attain optimal results and also supply cleaning quickly.

We provide discount rates for those that use the solution for the first time, along with favorable regards to cooperation for regular customers.

Our friendly team offers you to obtain acquainted with desirable regards to cooperation for business clients. We sensibly approach our tasks, tidy making use of professional cleaning items as well as customized devices. Our workers are trained, have clinical publications as well as recognize with the nuances of getting rid of complicated as well as hard-to-remove dirt from surfaces.

We offer premium cleaning for huge enterprises as well as little firms of numerous instructions, with a discount rate of as much as 25%.