Charles van Onselen’s new book offers a gripping narrative, a witty voice dripping with matchless sarcasm, and unparalleled knowledge of the early Rand’s history.

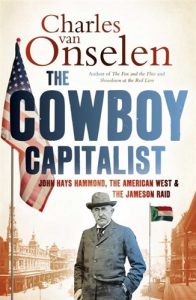

The Cowboy Capitalist: John Hays Hammond, the American West and the Jameson Raid

Charles van Onselen

Jonathan Ball Publishers (2017)

Charles van Onselen, a research professor at the University of Pretoria and surely one of the leading social historians of the modern South African experience, has long had a knack for finding kernels of enormous historical significance in the most mundane of circumstances.

Several of Van Onselen’s books about the criminal underworld that emerged on the Rand during the last two decades of the nineteenth-century have won prizes. He maintains a well-deserved reputation as a master storyteller of some of the seamier aspects of the mad rush to build a capitalist entrepôt on top of the deep-level mines that did so much to shape South Africa’s modern political economy. His earliest work in this vein consisted of short case studies, sharply drawn portraits of thieves, social bandits, prostitutes, washermen, domestic servants, liquor dealers, and, for lack of a better term, early Johannesburg’s lumpenproletariat. But his two most recent doorstoppers, Masked Raiders: Irish Banditry in Southern Africa: 1880-1899 (2010) and Showdown at the Red Lion: The Life and Time of Jack Mcloughlin (2014), are almost baroque in their efflorescent detail.

That also proves to be the case in his new book, The Cowboy Capitalist: John Hays Hammond, the American West and the Jameson Raid, in which Van Onselen revisits the well-known effort of Cecil John Rhodes and Leander Starr Jameson to foment a revolution in the Transvaal (then known as the South African Republic) in the waning days of 1895. In an effort to bring the Transvaal’s richly endowed goldfields into the orbit of the British Empire, Rhodes, Jameson, and their co-conspirators sought to unseat Paul Kruger and install a ‘reform’ government more amenable to British imperial domination and its accompanying economic development of the region’s rich mineral deposits. Like most materialist historians, Van Onselen regards the Jameson Raid as pitting ‘the limitations of an agricultural state centred on Pretoria’ against ‘the rapidly gathering strength of industrial capital located in Johannesburg’ and a ‘precursor to the globalised struggle for control of the country’s mineral wealth’ that broke out a few years later.

At the time, however, the ill-conceived Jameson Raid, as ‘one of the worst-kept secrets in military history’, proved remarkably inept. Yet, through intrepid research, Van Onselen has elevated to cardinal importance the role played by the third Jameson plotter, namely the American mining engineer John Hays Hammond. Having been sentenced to death for his participation in the aborted revolt, Hammond spent the rest of his long political and economic career obfuscating his place in this sordid history. In one sense, Van Onselen here returns to one of his earliest themes, ‘the world the mine owners made’, so memorably sketched in the opening essay of New Babylon, the first volume of his Studies in the in the Social and Economic History of the Witwatersrand, 1870-1914. Now, however, he tells this familiar tale from an entirely new angle, insisting that its roots should be traced to Gold Rush California, the American Southern Confederacy, and the hard-rock mining frontier of the American West, rather than to the boardrooms of London or the barroom of the Rand Club on Commissioner Street.

Much of the basic narrative of the early economic and social development of the Rand recounted in this book will be familiar to students of South African history, in large part because of nearly four decades of spadework conducted by Van Onselen himself, and a generation of his students. The novelty comes in his insistence that the Transvaal benefited from an infusion of frontier capitalist culture imported by American mining engineers like Hammond, which ironically made it easier for the Boers to fend off the incursions of the British empire. The two thousand-odd Americans transplanted to the Rand helped plant American technology, goods, know-how, and even republican values (and, of course, racism), in the fertile political soil of the Transvaal during the eighteen-nineties, Van Onselen contends. Even while Hammond adopted a role as a collaborator with Rhodes and the British Randlords in their effort to displace the Boers from their perch atop valuable gold deposits, he and his fellow Americans served as a potential counterweight to their imperial influence. Their popular instrument—borrowed, Van Onselen suggests, from the frontier US West—was the ‘vigilance committee’ determined to enforce law in the name of citizens. As the bungled Raid quickly fell apart, Hammond himself transmuted rather quickly from ‘aspirant revolutionary to reluctant reformer’, posing as a stalwart, if unlikely, Republican rather than the Anglophiliac imperialist he had appeared to be at first glance. Barely slipping the hangman’s noose, this wily operator ‘succeeded in selling to the world the fiction that the mine owners had never been intent on fomenting a revolution’.

Hammond’s ability to escape both the short- and long-term consequences of his participation in the treasonous revolt ultimately flowed from the fact that he was exceptionally well-connected with the elite on the other side of the Atlantic. He and his Southern-born wife, Natalie Harris Hammond, claimed friends and allies through associations with military leaders, Ivy League graduates (Hammond had attended Yale) and the growing fraternity of mining engineers. Eventually securing a pardon from Oom Paul Kruger—with a little nudge from Oom Sam—Hammond departed southern Africa with his tail between his legs. Only a concerted campaign to repair his damaged reputation, initiated by a ‘memoir’ ostensibly penned by his tough-minded wife, and perpetuated by obliging friends in the press corps, allowed Hammond to return to the US and reclaim his exalted position among the country’s elite. Hammond’s most effective scribe, Van Onselen shows, was the ‘yellow journalist’ Richard Harding Davis, whose journalistic sabre-rattling in 1898 encouraged the US to invade Cuba and thus officially join the ranks of imperialist nations. By the time Hammond engineered his re-entry to the US in 1899, his ‘involvement in the Jameson Raid seemed less out of step with … the evolution of American foreign policy’, Van Onselen remarks drily. Judging from his subsequent attempt two decades later to foment rebellions in Revolutionary Mexico to align with his investments there, ‘Cowboy Jack’ does not seem to have learned his lesson, though he continued to cozy up to journalists eager to help him burnish his reputation as a daring man of action.

Hammond’s brief exile from the A-list echelon of men of late-Victorian manly success, it turns out, was an uncharacteristic experience for a character whom, in Van Onselen’s telling, emerges as a remarkable fellow. Raised in gold-rush era San Francisco on a steady diet of tales of ‘filibustering’ American expansionists, Confederate heroes, and swashbuckling adventurers, Hammond became the epitome of the rough and tumble scramble for resources that characterised the American West’s absorption into the capitalist marketplace during the last third of the nineteenth century. Hammond certainly was responsible to a great extent for embellishing his own ‘cowboy’ reputation; Van Onselen swallows most of it whole, and embellishes it further. Nevertheless, there is no question that in the year immediately preceding his 1893 employment by Rhodes as a mining engineer on the Rand, this quintessential American Robber Baron battled striking miners in Idaho in one of the most notorious showdowns between labour and capital to rock the American West. Indeed, as Van Onselen points out, if historians have ignored the connection between Hammond’s bare-knuckle tactics in Coeur d’Alene and his subsequent role in the Jameson Raid, labour activists at the time recognised him for what he was: an ‘international hireling of capital’.

To be sure, Van Onselen acknowledges the many local forces within the Boer Republic that made an attempted ‘putsch’ by those intent on a more efficient exploitation of the region’s enormous mineral wealth almost inevitable. Yet, with a typical single-mindedness, he insists that ‘Jack Hammond [was] the catalyst behind the events leading up to the Raid’. In rooting his narrative in this sort of overstatement, like his protagonist, Van Onselen tells a good yarn that may not hold up to close scrutiny. The Cowboy Capitalist is strewn with ‘may haves’, ‘must haves’, ‘would haves’, ‘almost certainlies’, and ‘had reason enough tos’—all sure signs that speculation has outstripped historical evidence. The role played by the brash American mining engineer in these events, as Van Onselen contends, is surely underappreciated; but did ‘discussions that took place between three men around campfires’ in Matabeleland in 1894 really ‘change the course of southern Africa’s history’?

It must be said as well that while Van Onselen offers a gripping narrative, a witty voice dripping with matchless sarcasm, and unparalleled knowledge of the early Rand’s history, his ‘discovery’ of Hammond’s role in the attempted coup of 1895 is not quite as original as he claims. In his massive tome on Rhodes, for example, Robert Rotberg suggested that Hammond’s skeptical assessment of the mining possibilities in Southern Rhodesia actually catalysed the determination of the Colossus (Rhodes) to make the Transvaal central to his scheme of a unified southern Africa.

Hammond’s ‘puffed up’ 1935 autobiography, which Van Onselen rightly criticises for downplaying his protagonist’s role in the Raid, does contain some interesting elements that are overlooked in the zeal to portray Hammond as the personification of ‘frontier-like greed and opportunism’. Though often described as a conservative, Hammond was in the American political context a Progressive Republican. A confidant of Theodore Roosevelt, a close friend of William Howard Taft, and a participant in the National Civic Federation, Hammond came to believe that ‘responsible’ trade unions had a place in the American economy. He even accepted that negotiation, collective bargaining, and arbitration on the labour question were possible, indeed desirable, at least in the United States, and went so far as to state that ‘organised labor was needed to protect the workingman against organised capitalism’. He also supported minimum wage legislation and safety inspections. Of course, none of this seemed incompatible at the time with a full-on embrace of racist imperialism: Hammond happily advocated enslavement of African workers back on the Rand, imbibed the eugenic-tinged ideas about race and immigration typical of his class at the time, and proved more than willing to invest in King Leopold’s Congo. Nevertheless, Van Onselen’s effort to shoehorn Hammond into a representative of the Confederacy and the Old South is something of a stretch.

Van Onselen may try some ordinary readers’ patience as he recounts in enormous detail the machinations of competing Boer political factions in the South African Republic in the run-up to the Raid, and the political horse-trading that ensued in the aftermath of its ignominious collapse. Historians may greet some of his more florid speculative passages with raised eyebrows. And, of course, anyone with a shred of affection for the ‘manipulative, rapacious, self-serving imperialist’ at the heart of this book may find the relentlessly negative portrayal of the ‘cowboy capitalist’ not to their taste, even if they appreciate his importance in the saga that the book recounts. But if this rollicking tale suffers from some of Van Onselen’s trademark penchant for making marginal historical figures and small matters loom overly large, it nonetheless reminds us of the deep entanglements between the frontiers of naked capital accumulation in North America and southern Africa during formative periods in the industrial history of both regions.

- Alex Lichtenstein, a frequent contributor to the LA Review of Books, teaches South African and US history at Indiana University and is editor of the American Historical Review. Follow the AHR on Twitter.