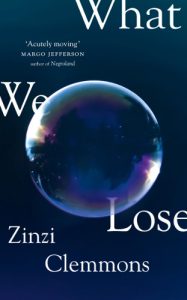

What We Lose

Zinzi Clemmons

Fourth Estate, 2017

Memory itself is an internal rumour

—George SantayanaBut most of what I experience is secondhand, from my family and the news

—Thandi

A print of a painting by Andres Orpinas, the Chilean Romantic landscape artist, has hung in my parents’ bedroom for the full course of their nearly thirty-year marriage, a marriage as long as I am old. My interest in it may have lessened over the years, but when I was a child it seemed to demand close inspection. In it, two birds perch majestically on the scraggly branch of a tree in a golden forest, and in the distance is what appears to be a farmhouse. The mysterious and idyllic nature of the scene was at odds with my reality growing up. At first, in the years before 1997, it felt alien to me against the backdrop of the manicured miniature gardens of the township in which I lived; later, it came up against the lushness of the foreign plants my parents tended to, and still do today, hacking away at the foliage year after year in the pursuit of neatness. I assumed that the painting depicted some part of South Africa I did not yet know; I assumed the artist was white and Afrikaans-speaking. South Africa, for the most part, was a secondhand experience for me at that age. It was essentially unknowable.

Thandi, the protagonist of Zinzi Clemmons’ debut novel, What We Lose, also has a secondhand experience of South Africa. Hers is a South Africa as seen from her parents’ home in Philadelphia in the USA. Despite her obsession with it, her experiences of the country are disembodied, and she lives inside a jumbled scrapbook of the identities she is called to answer for—South African, American, female, upper-class. Shake the scrapbook and what falls out from the South African pages—blog posts, articles from the popular press, photographs, testimonials from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, family anecdotes—provides texture to Thandi’s overwrought, petrified imaginings of the Bogey Man lurking beneath South Africa’s uneven exterior. Crime and lawlessness thus feature prominently in the novel, and the national neurosis attached to them is placed under scrutiny.

Thandi, the protagonist of Zinzi Clemmons’ debut novel, What We Lose, also has a secondhand experience of South Africa. Hers is a South Africa as seen from her parents’ home in Philadelphia in the USA. Despite her obsession with it, her experiences of the country are disembodied, and she lives inside a jumbled scrapbook of the identities she is called to answer for—South African, American, female, upper-class. Shake the scrapbook and what falls out from the South African pages—blog posts, articles from the popular press, photographs, testimonials from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, family anecdotes—provides texture to Thandi’s overwrought, petrified imaginings of the Bogey Man lurking beneath South Africa’s uneven exterior. Crime and lawlessness thus feature prominently in the novel, and the national neurosis attached to them is placed under scrutiny.

I recently spent a night back in the home of my childhood, and I found myself unable to sleep. I was now, all these years later, unable to ignore the jagged spikes that sit atop the perimeter fence, pointing to the sky and looking like spears, unable to ignore the security company’s ominous confirmation, on that same fence, that we are part of their mafia-like protection network, unable to keep from my mind the huge black block of a gate that shuts off our way of life from onlookers. Frequent petty thefts and home invasions—for years the subject of our nervous amusement—have turned violent and drug-related. The childhood in which we could laugh off these threats is long gone. In What We Lose, Thandi’s own fears are divorced from any direct knowledge of the terrain that plays host to them, and her terror is therefore all the more incapacitating on her short visits to the country.

Thandi’s dispassionate first person narration impresses on the reader the sense that she is not one to interrogate things too deeply, but that she endeavours to be honest and forthright in her thoughts and conclusions. This works well when Thandi is describing her upbringing and early adulthood. The perspective is simple and the prose unencumbered, it would not be out of place in a young adult novel. It certainly has its charms: it is nostalgic in the way American high school sitcoms can be to South Africans. This, though, is the same narrative voice that is put to use to when Thandi starts considering the various ingredients that go into her views on identity. Questions of race in the US and South Africa—Thandi identifies as a black American, while her cousins, despite looking like her, are so-called ‘Coloured’ South Africans—head the list, which also includes anti-blackness, colourism, xenophobia, class, interracial relationships, natural hair, affirmative action and feminism. Though undoubtedly meant as a thorough representation of the going concerns of today, these issues, which permeate the novel, at times become cumbersome.

They intrude too obviously, for example, in Thandi’s experiences with her townie, deadbeat first boyfriend, who never goes to college and verges on comic cliché, or during her African Studies class. Like the protagonist of the television show Dear White People she, a light-skinned, curly haired woman of mixed race, is the more radical and theoretically sound student when considered alongside a dreadlocked slam poet named Devonne—whose darker skin, the story implies, makes her jealous of the advantages bestowed on the narrator. One sentence in particular speaks to Thandi’s self-consciousness, revealing both her level of perception, and an attitude that carries through her story: ‘I idealised this group [black Americans] as one does a storybook character or a superstar, or anything one doesn’t know firsthand yet loves like an old friend.’

This is a view shared by Thandi’s South African cousins, who see black Americans as cool and black South Africans as ordinary, even dangerous—a function of proximity, familiarity and, of course, the apartheid-engineered racism and spatial planning that have made sharing a country a constant secondhand experience: no matter where you are in South Africa, your sense of what it’s like to be somewhere else—even if it’s just down the road—is always mediated. Your view is reminiscent of mine, gazing at that Andres Orpinas landscape, wondering which rural dorpie it portrayed.

This secondhand perspective, which can be simultaneously superficial and charming, does not transfer well to the book’s core concern, which is grief. Though the grief here is Thandi’s own—she loses her mother to cancer—she displays the same remove from her authentic feelings of loss as she does in her nostalgic musings on her early life. Her reliance on, for example, grief pamphlets, Newtonian physics, geometric diagrams, Buddhist tracts, feminist scholarship, life-expectancy graphs, self-help websites and excerpts from the autobiographies of Barack Obama and Nelson Mandela, may comprise an impressive and eclectic resource list for grappling with life’s realities, but the book does not rise to the level of insight promised, even as the descriptions are often arresting and contemplative. The desperation of Thandi’s grief is clear, and its devastating effect on the lives of those affected by it profound, but grief as a feeling is not conveyed viscerally. In a particularly tone-deaf moment, in trying to describe the sense of middlehood she has felt her whole life as a mixed-race woman, considered foreign and class-privileged in America—and now also conspicuously different because of her mother’s illness—Thandi describes this feeling as apartheid.

What We Lose is the poignant portrayal of a critical event and the fall that follows. Thandi doesn’t ever experience the flourishing of the American dream for which she was so clearly reared and groomed. Like the Newtonian laws she uses to help understand her grief, her life moved at a constant velocity before it was acted upon by an outside force, death. This force requires that she break away from convention and simplified conclusions, but the path she takes unfolds as if inevitable—and for those outside of her subjectivity, this inevitability is painfully predictable.

Index

Authors

- Zinzi Clemmons

Books

- What We Lose

Topics

- Andres Orpinas

- American high school sitcoms

- Colourism

- Dear White People

- Grief

- Racialism

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission