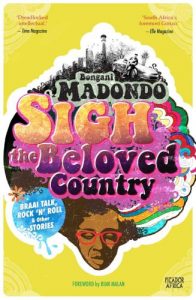

Sigh the Beloved Country: Braai Talk, Rock ‘n’ Roll & Other Stories

Bongani Madondo

Picador Africa, 2016

Load up on guns, bring your friends

It’s fun to lose and to pretend

She’s over bored and self assured

Oh no, I know a dirty word

—Nirvana, Smells like Teen SpiritI’m a black writer by choice and by experience.

—Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’oA little magazine is like the start of a river … We don’t know how long they will live, and they often disappear; but better to disappear than to become a bad magazine.

—Etel Adnan, ‘On Small Magazines’, Bidoun Magazine

In this reworked excerpt from his collection of essays Sigh the Beloved Country, Contributing Editor Bongani Madondo muses on how the Pan-African journal Transition, Vibe magazine and a buncha American Glossies Put Him on the Write Path.

When I came around to it, Rajat Neogy’s now iconic and provocative essay ‘Do Magazines Culture?’, published in 1966 in issue 24 of Transition—the periodical he founded in Kampala—stamped its psychic footprints on my mind in ways I have yet to shake off. Can’t say I’m exactly in a hurry to.

When I came around to it, Rajat Neogy’s now iconic and provocative essay ‘Do Magazines Culture?’, published in 1966 in issue 24 of Transition—the periodical he founded in Kampala—stamped its psychic footprints on my mind in ways I have yet to shake off. Can’t say I’m exactly in a hurry to.

To this day, I cannot say fo-sho if it was his rhetorical manner of posing the question, or the substance with which he wove, threaded and anchored the argument on the role of magazines in our—Black and brown folks’—complex lives and self-perceptions that kept me awake all these years.

Sure you can relate? D’y’know that feeling that strikes you that someone could be on to something, though what exactly that is needs a bit of sweating hard on the small stuff, paying a bit more attention or just kicking back and waiting with a hunch in your belly that the essence of what’s being hinted at will somehow reveal itself?

That’s how I felt, listening to Neogy’s question, for it indeed sounded like music to me. What genre, we’d soon found out.

Or not.

Neogy’s song done gone hooked me on that specific essay and the magazine itself. Coming of age in several spaces—honey, told you my momma was a rollin’ stone; a single black queen down on her luck, perennially search of a convenient home to raise a bunch of us—in this village here, that village there, and, hey over there … across the main road beyond the green patch of veld the size of a gigantic soccer field where the village’s cattle grazed, you will arrive at Leboneng, the Old Money freehold north-west of Pretoria, where I grew up curious, insufferably restless.

Other than my mother’s own built book and magazine collection (books were books and not ‘texts’ then) the broader culture within which I came up was barren, that’s if literary entertainment was your kind of thing. As it was mine.

Because of such luck, unlike mamma’s boss Baas Attie le Roux’s son Rian, same age as me and who grew up on intellectual literature, I only got to read proper journals much more later. It makes sense then that I was only introduced to Neogy’s cool, if a bit intellectually gladiatorial journal long after my contemporaries elsewhere in the world had heard of, read, nah, worshipped at its altar. And long after it had decamped from Kampala to Accra and from Accra to Harvard University, where it is still grazing.

The lucky ones among my generation—late 1960s-early 1970s, post-pill and rock ’n’ roll symphonic farts and geniuses travelling at the speed of light to fuel hippie revolutions from Manchester to Bamako—went on to contribute to it, under its revolving door of editors from Anthony Kwame Appiah and Henry Louis Gates Jr to Michael Vasquez, Kelefa Sanneh, Tommie Shelby, Vincent Brown, and so on.

I first got acquainted with Transition in 1999 through a new friend, the late England-raised Nigerian writer Ken Wiwa, scion of the famous poet famously slain by the man known as The Butcher of Abuja, General Sani Abacha.

Wiwa junior, a gifted storyteller with a singular writer’s voice distinct from his father’s, arrived in Johannesburg to work on a chapter for his memoirs In the Shadow of a Saint. He arrived to interview children of South Africa’s ‘Struggle Royalty’—Nelson Mandela and Steve Biko—in between paying courtesy calls to Archbishop Tutu and saying hello to ‘Aunty’ Nadine Gordimer. I envied his unearned, genetic struggle credentials. For a stupid while, I too wished my dad had been murdered by a whore-lovin’ dictator. Knowing safely that my daddy was long dead, dying without even the courtesy of meeting me when he was alive.

Bastardo!

1999 it was.

Wiwa junior’s fellow Bri-Gerian (as I jokingly refer to cosmopolitan Nigerian children born to first, second or third generation Middle Class parents in Britain) Emeka Nwandiko, then based in Johannesburg, brought him to my digs in Yeoville for dinner.

This one-time Jewish bohemian village had morphed into a loud, rowdy and sexy African mini-metropolis, slap-bang on the east wing of the Sin City, Mjipa, Jozi itself. Two weeks later Wiwa and I were still at the dinner table. Discussing everything and everyone there was to discuss; harmlessly gossiping a bit about other writers, as is writers’ nature; admiring and quarrelling with their ideas and exchanging notes on literature, specifically magazines and journals.

Why journals?

Having trained in journalism, I suspect we suspected each other of not being proper writers, whatever that might be.

Just when Wiwa was about to leave, heading back to London, Naija or Canada where he was on a writer’s residency, the brother pulled two dog-eared books out of his rucksack by way of settling his lodgings bill. Naaa-gee-rianz!

He needn’t have settled anything-o. I already felt way over-compensated just by his presence.

Spending time with another writer, especially one with a different background to yours, is gold dust for writers, and I believe all sorts of artists. For me it was like owning a gold-stock in the transient cultural stock exchange that binds us all in this biz called journalism and so-called ‘serious’ literature.

‘Haba! Oga-o,’ he playfully shouted. Pretending to be outraged by the thought. ‘You mean you have not come across or read these?’ Wiwa slapped a brand new copy of Transition magazine, and Salman Rushdie’s essay collection Homelands on the kitchen counter. They fell with a bass-ly twuck!

Thumbing it towards my face: ‘Ey-yo, there’s just no way you have not come across this, nah, broddah.’ (For a Middle Class Nigerian raised in tony schools in England, I felt a sickening and excitable hunch that Wiwa, as well as a truckload of my double-passport bearing Naa-gee-rian friends suffered from a class guilt. Thus that exaggerated everyman’s Naijah accent.)

With that … swoosh! he was gone. Leaving a copy of what was once Neogy’s ‘baby’, which, in the Johannesburg summer of 1999, had long since found a home, at Harvard’s Institute for African and African American Research, currently known as the Hutchins Centre—far away from home geographically, although scarcely removed, I’d love to believe, in spirit and symbolism, from its founder’s cultural and literary ambitions.

Although we know how what is often passed off as the holy grail can mask a reluctance to change and and resistance to self-critique, and often collapses under its own canonical symbolism. A snarky friend once warned me that only public amenity structures needs signs and symbols: writers and stories must sink them both. We don’t need them, even if powerful people do not stop using them to douse our fire.

It is fifteen years since Wiwa left and the question he inadvertently came bearing—like a tweeting bird flip-flapping over the vast African borders, across the Atlantic—on behalf of Neogy, haunts me to this day: Do Magazines Culture?