Firepool: Experiences in an Abnormal World

Firepool: Experiences in an Abnormal World

Hedley Twidle

Kwela, 2017

The following is an excerpt from Firepool: Experiences in an Abnormal World, a new book of essays and creative non-fiction by Hedley Twidle. We pick up with section 18 of ‘Twenty-Seven Years’, a reflection on the lives of three men who carried the hopes of South African music and literature in the 1990s: Moses Taiwa Molelekwa, one of South Africa’s greatest jazz prodigies, who died in 2001 at the age of 27, and the novelists Phaswane Mpe and K Sello Duiker:

18

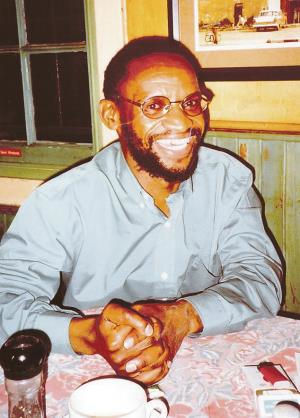

Phaswane Mpe (1970–2004)

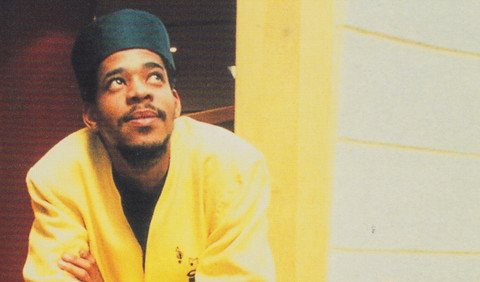

Moses Taiwa Molelekwa (1973–2001)

K Sello Duiker (1974–2005)

Three talented men, three great hopes for a post-apartheid South African

culture, gone too soon. The first an academic and novelist, author of the strange and prophetic short work Welcome to Our Hillbrow (2001). The second a pianist and composer, whose major works are Finding One’s Self (1993) and Genes and Spirits (1998), with Wa Mpona (2002), Darkness Pass (2004) and several live albums released posthumously. The third, the author of two key novels of the South African transition – Thirteen Cents (2000) and The Quiet Violence of Dreams (2001) – who was working as a screenwriter at SABC1 when he took his own life.

If Molelekwa carried the hopes of South African music in the 1990s, then for literature perhaps it was Duiker and Mpe. Yet each of these talented, troubled men would be dead before the end of South Africa’s first decade as a democracy, leaving a great sense of sorrow and emptiness. For me they are bracketed together: discovered together (late). What they share (Taiwa and Sello especially): earnestness, naivety. A voice that was vulnerable, that was still in the process of working itself out. The occasional false notes that come with the ambition of trying to get somewhere else, somewhere new. Also: an unwillingness to talk about the circumstances of their deaths. Can one listen to the 1990s through their work, at a time when the 1990s seems very far away, when a period that you lived through has now become historical?

19

In an interview, pianist Moses Molelekwa named his three biggest influences as Abdullah Ibrahim, Herbie Hancock and Bheki Mseleku. Ibrahim for his hard-won simplicity; Herbie for the way he treats the keyboard as a site of restless experimentation; Mseleku for his merging of jazz techniques and southern African melodic lines.

In finding out more about Bheki Mseleku – who suffered from diabetes and bipolar affective disorder, who spent two years on retreat in a Buddhist temple and many more in exile – I learned that he had once met Alice Coltrane in Newport. Here she gave him the mouthpiece that John Coltrane had used during the recording of A Love Supreme. When Mseleku returned to South Africa in 1994, this was taken during a burglary in Johannesburg – an event which, according to his 2008 obituary, ‘seriously destabilised him’. The mouthpiece Coltrane used in the recording of ‘Prayer’ and ‘Ascent’, a mouthpiece which he bit into, and which would have carried his teeth marks – this went missing in Johannesburg, perhaps dumped in a skip or a storm drain, perhaps finding its way to an unwitting musician. For weeks I carried around this footnote, stunned, not really knowing what to do with it.

20

‘Does life begin at 40?’ asked an online tribute to a South African pianist and composer who died in 2001 at the age of 27: ‘That’s the time signature Moses Taiwa Molelekwa would have reached on Wednesday, 17 April 2013.’

‘Time signature’ is a musical term for the number of beats in a bar. I want to stretch it to consider the musical signature of a time – 1994 to 2004, the first ten years of South African democracy – that is by now a historical period. Now when an album like Molelekwa’s Genes and Spirits or a book like K Sello Duiker’s The Quiet Violence of Dreams, which once seemed so contemporary, have become period pieces. So what does it mean to listen to those years, in both Molelekwa’s playing and the verbal signature of Duiker’s prose?

For me these two artists have always been mixed up with each other, and with a series of visits back to a rapidly changing country during my twenties. I would return from the cold northern hemisphere to Cape Town, rent a room in Observatory and begin conducting my ‘research’. Mostly this involved wandering alone around the city and visiting record shops, since music seemed to disclose, ahead of any other form, the shape of things to come: making audible what would gradually become visible.

Quiet Violence is a book with music threaded all the way through it: timeless sounds like Cesaria Evora and Peter Tosh, but also references to club anthems and compilations that date the work quite precisely, and even comically: seeing Café del Mar and Jamiroquai referred to as the acme of hipness makes me smile now. Near the beginning is a long passage in which the main narrator, Tshepo, describes Cape Town nightlife, suggesting that designer clothes matter more than racialised histories:

[N]o one really cares that you’re black and that your mother sent you to private school so that you could speak well. No one cares that you’re white and that your father abuses his colleagues at work and calls them kaffirs at home. On the dance floor it doesn’t matter what party you voted for in the last election or whether you know how many provinces make up the country. People only care that you can dance and that you look good. They care that you are wearing Soviet jeans with an expensive Gucci shirt and that you have a cute ass.

As the passage goes on, the young hedonists all begin to coalesce into some kind of new, consumerist, post-millennial South African on the dance floor: ‘The people I know never forget that in essence the difference between kwaito and rave is down to a difference in beats per minute and that the margin is becoming narrower.’ It’s hard to tell the ratio of utopia to dystopia (or irony to sincerity) in this vision; it’s difficult to know whether they are liberated or trapped in music – and the protagonist is, after all, in a mental institution for ‘cannabis-induced psychosis’. But the idea that black, brown and white are going to melt into each other on the dance floor, are going to meet in the middle with regard to BPM – that version of the contemporary also seems very distant now.

But it’s less the writing explicitly about music than the tone colour or timbre of the prose that I am thinking of. Duiker’s works are harsh, unrelenting. His prose seemed to capture the beauty but also the menace of a city that I was just beginning to know. Even in the lyrical parts of a book like Thirteen Cents, there is the sense of something controlling and sinister just out of vision, just behind the pastoral façade: ‘When I wake up I can only feel the sun on my face. The shadow has moved. It’s the sun. It does that to everything. It moves things.’

As a form, the bildungsroman (or coming-of-age novel, of which Quiet Violence is a queer, postcolonial variant) generally lends itself to a lonely, alienated voice. Just as it is easier to reach for a dark and diminished minor chord on the piano when feeling angst-ridden – the hands fall naturally into that pattern. The result is that Sello keeps hitting the same notes: sounds and sentences that take themselves very seriously, short sentences that are arranged in a tight holding pattern for the weight of emotion and social trauma they are expressing.

Trying to express similar things in major keys, though – that is a different exercise.

21

In his autobiography, Blame Me on History, Bloke Modisane writes about Johannesburg’s Sophiatown in the 1950s, the ‘Fabulous Fifties’. The book sounds a discordant note in the mythology that has grown up around the era. He recalls moving in white liberal circles in which he was treated as a curiosity: ‘Most of them were visibly struggling with the word “African” which was almost always one beat too late.’ He goes on to catch something not often put into words, something about how South African sorrow and entrapment sound out in major keys, and something that I keep coming back to in thinking about the life and death of the pianist Moses Taiwa Molelekwa:

[M]y life is like the penny whistle music spinning on eternally with the same repetitive persistency; it is deceptively happy, but all this is on the surface … beneath all this is the heavy storm-trooping rhythmic line, a jazzy knell tolling a structure of sadness into a pyramid of monotony; the sadness is a rhythm unchanging in its thematic structure, oppressive, dominating and regulating the tonality of the laughter and joy.

22

I should admit that many of the tracks on Finding One’s Self, the debut album by Molelekwa, are just too smooth for me: too melodious, even a little kitsch. I find myself listening between and through those over-produced numbers to hear the parts when the cheesy guitars and synths cut out to leave just the fundamental trio: the deep grammar of piano, bass, percussion. Or just the solo pianist at work, as on the double album released after his death, Darkness Pass. On it we hear Moses thinking things through at the keyboard in real time, puzzling out specific solutions to specific problems: ‘Crouched over his piano working through something intricate,’ writes Binyavanga Wainaina, ‘caught in the most fragile of places, trying to juggle things at the furthest reaches of his ability.’

23

‘I went through a couple of books to see how people describe musicians, you know,’ says the pianist and composer Moses Taiwa Molelekwa in an interview recorded in the late 1990s, ‘how people describe music. And I haven’t really found a satisfactory answer.’

- Firepool: Experiences in an Abnormal World was published by Kwela in June

Lovely, now I want to read more. Will buy the book.