The Art of Life in South Africa

Dan Magaziner

UKZN Press, 2017

Main image: Ndaleni group shot, late 1970s, Ndaleni Scrapbook 4, with the permission of the Campbell Collections of the University of KwaZulu-Natal

Daniel Magaziner was in South Africa recently for the launch of his new book, The Art of Life in South Africa, and took some time to chat to Johannesburg Review of Books editor Jennifer Malec.

Daniel Magaziner was in South Africa recently for the launch of his new book, The Art of Life in South Africa, and took some time to chat to Johannesburg Review of Books editor Jennifer Malec.

Magaziner teaches South African and nineteenth- and twentieth-century African history at Yale University. His first book, The Law and the Prophets: Black Consciousness in South Africa, 1968–1977, was published in 2010.

In The Art of Life in South Africa, Magaziner challenges the dominant narrative of black life under apartheid by exploring how a small group of aspiring artists, at a remote training college in the Natal Midlands, carved out a life for themselves.

Scroll down for an excerpt from the book.

Jennifer Malec for The JRB: The Art of Life in South Africa centres mainly on Ndaleni, an apartheid-era, government-funded art teacher training school outside Richmond in the Natal Midlands that has been all but forgotten. How did you come across this story?

Daniel Magaziner: Like most students of South African history, I had never heard of Ndaleni before I began to do this research. I was attempting to research the intellectual history of black artists during the twentieth century and was spending many hours in the basement of the Johannesburg Art Gallery getting frustrated because the voices and opinions of white reviewers were drowning up whatever artists’ voices I could access. I was reading a short biography of an artist named Dan Rakgoathe and learned that he had corresponded with someone named ‘L Peirson’. There were generous excerpts from his letters, which led me to think that these files might be a useful source, so I tracked them down at the Campbell Collections in Durban. Long story short, it turned out that L Peirson was the head teacher at the Ndaleni art school, where Rakgoathe had studied during the early 1960s, and that the Campbell Collections held the entire archive of the school, in a cabinet locked since the early 1980s. The Rakgoathe correspondence file was voluminous and it was only one among many similarly voluminous files.

The JRB: Why do you think Ndaleni has been neglected in South African art history?

Daniel Magaziner: I think there are many reasons why the school has been neglected in art history; I’ll highlight two. The first is that it was not in the strictest sense an art school and art history, both in South Africa and elsewhere, is a very elitist discipline that typically focuses on those artists who were trained and identified as such at the expense of those cultural producers who come from a different tradition and practice. Ndaleni was a teacher training institution, first and foremost; the students were to be art teachers, not artists. To this we can add the second element: it was a government school, run by and for the purposes of Bantu Education. This reality is at odds with the conventional wisdom on South African art, which has long been interested in the intersection between artists and resistance and certainly not interested in exploring the co-production of South African art and separate development. I surveyed art historical texts about black South African art from the 1960s through the present and this process of forgetting was quite apparent. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Ndaleni was well known both to people interested in South African art, both locals and internationals, before it was gradually effaced as other black artists with more ‘conventional’ training and politics rose to prominence. The end result of this was made quite clear in Wits University Press’s recent multi-volume collection, Visual Century, where the Ndaleni school earns a only a paragraph.

The JRB: Your first book, The Law and the Prophets, focused on Black Consciousness and the student and resistance movements of 1970s South Africa, when politics was seen as a ‘way of being’ and was a dominant force in the world of art specifically. In The Art of Life in South Africa, the picture is subtly different. Could you talk a little bit about that difference?

Daniel Magaziner: Like many Americans of my generation, I was first exposed to South African history through the lens of the struggle against apartheid. Steve Biko and Black Consciousness were a tremendous intellectual and political inspiration for me personally and I was fortunate to spend many years studying and writing about the movements and its times. But even as I continue to be fascinated and inspired by its politics, I have also begun to recognise that Biko and his comrades were exceptional (as revolutionaries often are) and not necessarily representative of a more widespread intellectual experience under apartheid. More common than those who ‘were’ against the system were those who strove to live along the grain of what the system allowed; this was true in South Africa and it remains true around the world, where the majority of human beings struggle to find meaning and self-definition within the realm of the possible, rather than by probing beyond current realities (as Biko had once done). The Art of Life in South Africa is very much about how people lived in conversation (and limited by) their perception of the possible, something I strive to get at by considering subjects such as the material limitations of art production, for example, as well as the ethical compromises that training at a government institution and teaching in Bantu Education entailed. My argument is a classically historicist one—the beauty and worth such historical subjects produced must be seen in the light of context in order to be assessed and understood.

The JRB: Some students had conflicted feelings about studying at Ndaleni, operating within the limits of Bantu Education or ‘collaborating’ with the apartheid government. One such student was Selby Mvusi, who went into exile in 1957 and became an accomplished artist, but never spoke about his time at Ndaleni. Could you tell us about how his story is reflective of a black intellectual experience particular to this time?

Daniel Magaziner: Mvusi is one of the most interesting people I encountered while writing the book. (I should note Elza Miles’s excellent new biography of Mvusi, recently published by Unisa press.) It’s important to understand that Ndaleni was one of a very small number of places where black South Africans could get an art education during most of its existence. Although the school was intended to train art teachers, not artists full stop, many aspirant artists saw the school as a logical destination. Mvusi was a Fort Hare graduate, talented and interested in art, who was among the very first students at Ndaleni and who began to make a name in fine art over the course of the 1950s. He eventually left South Africa and embarked on a decade of teaching and theorising art and design in the United States, Southern Rhodesia, Ghana and Kenya, before he passed away. Mvusi was undoubtedly one of the most talented artists to pass through Ndaleni. But even more importantly, he was the exception that proved the rule in that he keenly perceived what was happening around him and was in a position to refuse to compromise with South Africa’s realities. He pushed against them artistically and eventually he pushed against them politically and ideologically, first by leaving the country and then by embracing the idea that industrial design, not ‘tradition,’ ought to be the foundation of a modern African culture. He developed theories of the African twentieth century that were purposefully and pointedly at odds with apartheid’s theory. In other words, he lived against the grain of his reality, rather than work within the realm of the possible that apartheid constructed. In that sense, he was a revolutionary, whose passage through and connection to Ndaleni clarifies the majority of other people’s lives that went in a different direction.

The JRB: There are a number of tragic stories to come out of Ndaleni, and very few students managed to make a life as an artist—not only because of restrictions on movement and opportunities but also simply because of a lack of art materials. What do you think Ndaleni’s legacy is for South African art history?

Daniel Magaziner: On one level the answer is pretty much ‘nothing’, because Ndaleni has been totally forgotten and many people who consider themselves knowledgeable about South African art history know absolutely nothing about it. To some extent this reveals that in South Africa, as elsewhere, we’re still dealing with narratives of artistic becoming that still privilege the idea of individual genius rather that coming to grips with the systematic ways in which ‘art’ as a category is produced by social conditions, by politics, by economics, by race. Ndaleni’s art was conditioned by all of these forces, well before students actually began to create. And yet, even though they were so limited and constrained, art still proved profoundly influential in so many people’s lives. The sheer quantity and quality of the emotion in this archive overwhelmed me; so many people were impacted by the opportunity to sit down somewhere and to think about how best to express themselves, how best to say something in wood, in clay, in some other medium. In this sense Ndaleni confirmed a good deal of theory on which progressive ideas about art education are based: that all people, no matter their background or circumstances, benefit from time spent dialoguing with the material world and making things. This is an essentially humanist concept and a point made especially powerful for being proven even in the depths of apartheid.

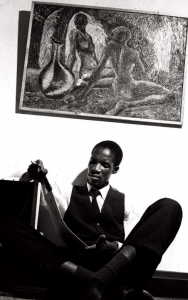

Ndaleni students such as Godfrey Ndaba, Dan Rakgoathe and Paul Sibisi managed to make something of a career out of art. But other Ndaleni students were not so fortunate.

Read an excerpt from The Art of Life in South Africa:

Samson Mahlobo studied with Peter Bell in 1962, during which time he completed a mural on the south interior of the Indaleni hall. It showed art students in bright, disordered clothes, merrily harvesting wood from the timber farm. Bell considered him ‘very talented’ but worried that he lacked the rigor and discipline to make it as an artist. Mahlobo was determined to prove Bell wrong.

In 1963, he established himself as a teacher at Zakheni Bantu School in Nigel, where he encouraged his students to explore new mediums and organised student shows. He continued to paint and sculpt, as well as to promote himself. ‘I’ve a number of charcoal sketches,’ Mahlobo wrote to Nat Nakasa in 1963, upon reading about Nakasa’s new arts and culture journal, the Classic. ‘I’ve got quite a lot in store for ‘your’ classic.’ He enclosed photographs of a concrete sculpture of Christ that he had recently completed, explaining that it was ‘NOT aimed at casting a Blasphemy or to Ridicule Christianity at all, [but instead] I made it under some inspiration I still cannot describe.’ Mahlobo loved being an artist. During 1963, a Johannesburg gallery displayed two of his sculptures, and he visited frequently, often with a group of ‘admiring females’ to whom he ‘proudly showed … his work.’

Yet Mahlobo did not find the going easy. He bemoaned apartheid’s impact on his career. Except for his time in Natal, Mahlobo had spent his entire life in Nigel, a Transvaal industrial town to Johannesburg’s south-east. As an aspiring artist, he reasoned that he needed to live closer to the big city and angled for access. The system made things difficult. Between 1963 and 1966, he repeatedly applied for and was denied permission to relocate to Johannesburg. ‘My life as an artist has been handicapped by … the laws of our South Africa here. …Were it not for the reason, I would have made tremendous progress thus far,’ he wrote to a supporter. Mahlobo threw himself into teaching instead, since ‘as a teacher I have not given up hope.’ Still, the dream of being an artist died hard, and he continued to apply for endorsement to Johannesburg.

He struggled for materials and access to the art world, and increasingly, he came to blame the state for his troubles. ‘I’ve been out of pockets,’ he wrote in 1964, ‘the reason—well, the law and so on. I’m afraid to comment too much on that.’ Like many other frustrated South Africans, he wanted to escape the country and begged his correspondents for any information about opportunities overseas: ‘I have no place to go to except abroad.’

He was stuck in Nigel, however, so he scavenged for materials and continued to work. He painted from pictures in the newspaper, producing works with titles such as ‘Soweto Train Victim’ and ‘Semi-paralysed Victim.’ He attended local jazz shows and asked overseas correspondents to send the latest Blue Note recordings to him, as well as ‘sportswear’—size medium—and stylish, lace-free moccasins. He continued to apply for permission to move to the cityand finally, in 1966, he reported: ‘They had first refused me permission to work in Joburg according to our influx control board and laws of our S. Africa, but eventually having appealed to Mr. Carr the Manager of the Bantu Affairs Department I succeeded.’ He was planning a one-man show, in hopes of building enough of a reputation to apply to study in Paris. ‘It’s really a matter of 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration that will lead me to success. Hard work really!’

Unable to secure lodging in the city, Mahlobo stayed at the ‘same old address’ in Nigel, and commuted back and forth to the gallery to which he had promised thirty works. The quantity was daunting; like so many others, he lacked materials and pleaded with his ‘beloved brothers and sisters’ from Ndaleni to help him out. The school had no stone and scarce wood, however and the show never materialized. Still, he schemed, first to return to Ndaleni to attend the 1968 refresher course—he was unable to do so because of a lack of funds—and then to continue his art education by writing matriculation exams and petitioning the University of South Africa (UNISA) to take him on as a fine arts student. For Samson Mahlobo, aspirant artist, the 1960s were an unrelenting struggle. ‘I think I’ll die if I miss this chance,’ he told a reporter for the Golden City Post when first he failed to gain access to Johannesburg in 1963. By the end of the 1960s, he apparently could no longer bear the strain, and he killed himself.

His death was a blow. ‘I didn’t know he was so unhappy,’ Hilda Mohlopi reflected, ‘his letters showed a happy-go-lucky person with a lot of humor.’ She had never met him in person—they were ‘pen-pals through ARTTRA’—but she had identified with his struggles across the 1960s: ‘I’ll miss him.’ The Ndaleni archive details other deaths. It has reports of ‘nerve breakdown or whatever people call it,’ depression, and alcohol abuse, it has information about certificate holders who were fired from their jobs and sent to rehabilitation centers. ‘He hopes eventually to return to teaching and a normal life,’ Peirson wrote about another student laid low by misfortune.

Given the challenges of living, the artful life was one best lived together. Art teachers spoke a particular language, and no matter how much success they had translating it to others, it helped immensely to ‘hear from people with whom you share the same feelings and ideas and are struggling together to make your presence felt.’ This is why Sophie Nsuza wrote so many letters to Lorna Peirson, even as her art practice faded away. To connect to the school was to bring Ndaleni—to bring Art—beyond the mission gates. Hearing from his fellow students convinced Dan Rakgoathe that he was ‘not utterly alone’ in the world. ‘Now that I have received ARTTRA, I feel at home,’ Priestess Xego sighed contentedly, ‘because before I felt that I was living in my own world with nobody like me.’ When reading the journal, she was convinced that ‘I am with people, though they are far from me.’ The school circular, shoddy and skimpy as it sometimes was, transcended space.

In the mid-1970s, four Ndaleni graduates found work around Madadeni, in the coal-mining region of northern Natal. None aspired to be a full-time artist (one was a serious long-distance runner, which hardly left time for anything else). Yet they came together nearly every weekend at one or the other’s home, ‘discussing our points on the field of art.’ It was, as Richman Simelane described it, ‘marvelous when we are around the table sharing our ideas and experiments.’ Life, like art, was a matter of seizing opportunities and transforming them, turning the raw material of proximity and presence into the intangible stuff of beauty. It was hard to do, but from time to time and place to place, it was also possible.

One thought on “Finding beauty under apartheid: Interview with Dan Magaziner, and excerpt from his book The Art of Life in South Africa”