Having been here for three weeks now, I think it should be considered an act of blasphemy to describe or even think of Cologne as just another beautiful city in Germany.

The word ‘beautiful’ fails in so many ways to capture the aesthetics and mystery, for example, behind the magnificent architecture of the iconic Cologne Cathedral. This is a city of multiple souls, with a unique power to unite all the people in it, irrespective of language, religion, race, nationality or sexual orientation. I’m humbled by the friendly atmosphere here every time I walk along the streets. It always makes me feel a pleasant rush of blood, rising from my toes and through my veins, giving me a warm sensation that is warmer than anything else.

‘Herzlich willkommen in Köln—welcome to Cologne!’ says my host Therese as soon as we meet at the Starbucks by the Hauptbahnhof.

I’ve just arrived from South Africa, and Therese is in charge of the Artists in Residence at the Academie. We have been communicating via email. I’m in Cologne for the whole month of June as an Akademie der Künste der Welt fellow. This fellowship aims to establish Rhine-South African relations. Authors Fred Khumalo and Rachel Zadok have been here before me.

‘Your residency is in Venloer Street,’ says Therese, not sure if she should help me with my only bag.

It’s Friday and the June morning sun is shining brightly. We walk towards the cream Mercedes-Benz metered taxi between the Cathedral and the Hauptbahnhof. It is summertime here. The tender green leaves of the trees along Komödien Street sway in the light wind. Up above the clouds are frolicking in the sky. I’m fascinated by the Cathedral, where hundreds of people are marvelling and taking pictures. A man near the door of the Ibis Hotel seems to be talking to himself with a camera around his neck. He makes gestures with his hands and brims with triumph and self-satisfaction. I’m not surprised at all. The striking, picturesque Cathedral is tantalising to the soul. It looks like a mysterious supernatural giant with a human heart and the ability to talk.

‘It’s always under construction, since 1248,’ Therese tells me, pointing at the scaffolding behind the Cathedral. ‘In 1880 they thought they had finished it. But as you can see it’s still under construction. It’s Germany’s most visited landmark, and attracts twenty thousand people a day.’

‘That’s a huge number. But why are they still building? It looks complete?’

‘I don’t know,’ Therese says. ‘People here believe that the world will end when it’s finished. So they make sure there is always something to renovate. It’s about postponing doomsday, I guess.’

It takes us about twenty minutes to arrive at my apartment, at the corner of Venloer Strasse and Akazienweg. My place is large, with three bedrooms, a kitchen, and a bathroom. All to myself. I’m going to enjoy this, I think. Therese confirms my Wi-Fi code, which is great because it means I don’t have to buy a German SIM card.

Before she leaves, Therese takes me to the basement-dungeon to show me the bicycle I can use. On our way here I saw lots of people on bicycles … but this is not something I would do. She hands me two keys, one for the bicycle and another for the rubbish bin.

‘We don’t mix rubbish here in Germany,’ she instructs. ‘You put paper and plastic in separate bins. There are lots of supermarkets along Venloer. Aldi is the cheapest and nearest. Rewe is big, but expensive compared to Aldi. By the way, the bicycle routes may be complicated for you in the first week. Have a good stay. Call if you need anything.’

Therese leaves. My first instinct is to take a bath and go back to the mysterious Cathedral. I know I have thirty days of writing, relaxing, blissful idleness, sleeping, daydreaming and walking, but I still have to see the Cathedral again today.

I connect my phone to the Wi-Fi and several WhatsApp messages pop out immediately. Some are from my friend Sine Buthelezi. She is currently doing her master’s at the Deutsche Welle Academie in Beethoven’s city of Bonn. It’s just twenty-five kilometres away from Cologne. By coincidence, as I’m reading her messages, she calls.

‘Welcome to Cologne,’ she says, before switching to isiZulu. ‘Kwaze kwabamnandi ukukhuluma isiZulu e Germany nawe. If you’re not tired I will come around nine to show you around the city.’

‘Nine? What will I see in the dark?’

‘Don’t worry. It’s summer here and the sun sets around ten,’ she tells me. ‘Nightlife starts around that time.’

Sine arrives, and is excited that we’re speaking isiZulu in Germany. She’s fluent in German as well, so I don’t have to worry that I don’t know the language. I know her from the Goethe-Institut in Johannesburg, where she used to host literary events. Sine is from Ngwelezane Township in KwaZulu-Natal and is very passionate about running, literature and literacy. She runs marathons around Germany and South Africa to collect money to buy children books. She tells me she is committed to this noble cause because most South African children don’t own reading books. I think this is an excellent initiative, remembering that when I was growing up in Soweto my parents could not afford to buy me and my siblings books.

‘The books come from a wonderful organisation called Book Dash. They are fundamental in creating stories that children can relate to and identify with,’ she says as we walk along Venloer Street towards the train station.

At the Akazienweg Station we take the Line 4 underground train to the city centre. It’s two euro eighty for a single trip, just over forty rand. I don’t have to pay because Sine’s monthly ticket allows her to tag someone along. The train is comfortable, an equivalent to our Gautrain. We find two seats and sit down.

‘You rarely see ticket examiners inside the train. But make sure you always buy your ticket.’

‘What happens if you don’t?’

‘They will fine you sixty euros. You don’t want to lose that kind of money for a two euro ticket. You can buy tickets at the machine at every station or inside the train. There’s an English option if you don’t understand German.’

We disembark nine stops later at Neumarkt in the city centre. I’m unable to hide my pleasure just looking around, as we walk along Schildergasse, the city shopping area. As an added bonus, we are walking towards the Cathedral. Everywhere the streets are buzzing with thousands of people milling about aimlessly. It’s already quarter to ten and the sun is about to set. The beauty of the last minutes of the day and the inner feeling of peace that comes with them fill me with rapture.

At a small shop we buy Karlskrone beer for me and a Beck’s for Sine. She is speaking in German as she tenders five euros and still gets change. The air in the streets is laden with the odour of aromatic food and strong coffee. Oh, such a freedom, I say to myself, and take a sip of Karlskrone.

‘Beer here comes in bottles and plastic,’ Sine says. ‘Only homeless people drink out of a plastic. But you can drink anywhere you want. There’s no law against public drinking.’

I prefer a plastic bottle, because it can twist open. With a dumpie you need an opener.

‘By the way, people here drink Kölsch,’ she continues. ‘Every city here in Germany has its own beer. People prefer a beer made from their own city.’

‘I’ll try it sometime,’ I say.

‘There’s some kind of rivalry between Cologne and Düsseldorf when it comes to who has the best beer. It’s rare that you find Cologne people drinking beer from Düsseldorf. And one other thing, when someone says “cheers”, or “prost” in German, you must look at that person straight in the eyes. Otherwise they believe it’s seven years of bad sex.’

We laugh. The daylight is slowly fading away as we reach the extraordinary Cathedral. It’s about ten. There are hundreds of people standing as if hypnotised all around the Cathedral. I start to feel a bit guilty drinking Karlskrone instead of Cologne’s Kölsch. I let my eyes roam freely, lingering on the colourful scene of the Cathedral’s bluish night lights. I feel a surge of renewed vigour inside me.

‘It’s a miracle that humans designed and built this for 632 years’—the words slip from me automatically.

‘The Germans are very patient,’ Sine says. ‘You can see by the way they cross the street. Even when there are no cars they wait for the green man on the traffic lights. Everything here is in order, and that’s why their country is working. The pavement is shared by people on bicycles and walkers. When you take an escalator, make sure you stand on the right so that those in a hurry may pass you on the left.’

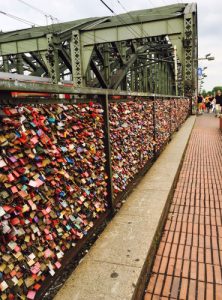

After taking a few pictures we walk the short distance to the giant Rhine River. Hundreds of people are walking slowly over the Hohenzollernbrücke, the bridge that joins both sides of the city. The sun has just sunk behind the horizon, making this still river a silvery shimmering sheet of water. There are thousands of padlocks dangling, right to the end of the bridge. I’ve read about this symbol of unbreakable love in Europe. Sweethearts inscribe their names or initials on the padlock and throw away the key. Some of them are rusty, and they seem to be weighing the bridge down with a deep sense of mystery and secrets of love buried in the distant and not so faraway past.

Trains are crossing to both sides of the Rhine. I see an old couple pointing at a rusty padlock. Down below are big, stationery boats.

‘Do people swim here?’ I ask, as I look down below to try and measure the width of the river. It looks like the size of two soccer fields to me.

‘I haven’t seen people swim before.’

We walk back via the Deutzer Brücke, with its parade of the magnificent scenery of the city. The nightlife at Heumarkt is ongoing, and people are drinking, walking, smoking, kissing, or eating in the open spaces, pedestrian walks, restaurants and bars. Our night ends with us buying two delicious pork belly sandwiches, at seven euros each. We also buy Karlskrone and Beck’s, which we enjoy by the soothing coolness of the river.

‘I’ll see you at your reading at the Akademie on Tuesday. I have to take the one o’clock train back to Bonn now,’ Sine says, looking at her watch.

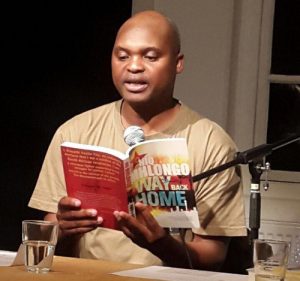

My reading at the Akademie is on at seven in the evening. Gunther Geltinger, the writer who translated my book Way Back Home into German, is reading a chapter from the German version. I’m reading the English version. Guy Helminger, a well-known author from Luxembourg, is our moderator, and Jutta Himmelreich is translating to me in English. About sixty people are in attendance and the house is full.

I meet lots of people before the reading. A few people have read my work, as I can tell from the questions from the audience. They ask about politics, corruption, and apartheid. Way Back Home is relatively popular here, since my 2015 tour of sixteen cities in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. People here are interested in the African way of healing the wounds of apartheid that is explored in the book. They want to compare the dark pasts of Germany and South Africa and to find out how far we have come as South Africans. This includes questions about land redistribution, the Fees Must Fall movement, and corruption. I regret bringing just ten copies of Way Back Home from South Africa because there is a relatively long queue of people wanting to buy it. But at least they can order the German version from my publisher Wunderhorn in Heidelberg, Germany. Hopefully they do.

After the reading, Sine, Indra Wussow, Achim Mohné and I go for dinner at the oriental restaurant around the corner, near Friesenplatz. I finally try a Kölsch, while waiting for my meal of duck and rice. I met both Indra and Achim in South Africa a few years back. Indra is the one who recommended me for this fellowship. She is the founder and curator of the Sylt Foundation and the director of jozi art:lab, and Achim is a founder of Remotewords (you may remember them from my story A miracle under the apricot tree in Chi Town: How a writer came to name Maboneng, from issue 2 of The JRB).

After dinner, Gunther, Indra, Guy, Achim and I decide to go to a gay pub along the Mauritiuswall around Friesenplatz. Sine is attending class the next day, so she catches a train back to Bonn. We agree to meet again on Father’s Day, when she will be doing a race for her children’s books project. At the bar Indra orders a Corte delle Rose, which costs about fifteen euros. I continue with my Kölsch, which I buy at two-and-a-half euros a glass. We call it a night at around two in the morning and I walk to the Friesenplatz Underground.

‘I want to take you to my favourite pub, if you have time,’ Guy says as we walk to the train station. ‘It’s around here at the Belgian Quarter, 47 Aachener Street. The place is called Low Budget. Let’s meet on Friday at ten.’

I make my way to Low Budget that Friday, and find Guy inside, playing a game of dice called Schocken with a group of friends. The loser has to buy a round of drinks. The atmosphere is excellent, and the jukebox is playing some German rock music. Guy and his friends are all happy to see me, and everyone offers to buy me Kölsch. A few minutes later a young black guy and a German woman walk in. From the corner of my tipsy eye I catch them stealing glances at me. Guy is introducing me to all of his friends, including the owner of the pub. This is the great bar, I think. It looks like the meeting place of artists. One of Guy’s friends is the lead guitarist for a rock band; another is a bassist, another is an interior designer, Guy himself is an author. While drinking my fourth or fifth Kölsch, the young woman I spied earlier wanders across. I’m thinking she wants to ask for a cigarette from the bar, or maybe she has seen me at the reading.

‘Hi, I’m Rebecca,’ she says to me. ‘My friend and I are wondering where you’re from? We have made a bet on three countries each. He thinks you’re either from Cameroon, Uganda or Zimbabwe. I think you’re either from Cape Verde, Cameroon or Angola.’

‘I’m Niq from South Africa. Tell your friend that since you both lost the bet you have to buy me a Kölsch each.’

The guy comes over and introduces himself as Isunge. We sit in the pub until one in the morning.

Sine’s five-kilometre run is on the Sunday of Father’s Day at Media Park, walking distance from my place. She’s running with her friend and classmate Lina Friedrich. It’s a women-only run, and thousands are here for the two, three, five, or ten kilometre races. While Sine and Lina run, I have a few glasses of San Miguel beer, which costs three euros. Most men are in the pub next to the running track cheering the women on.

After the race, Sine, Lina and I walk to our favourite eating spot in Cologne: Kebapland. It is a Turkish restaurant along Venloer Street with delicious kebabs at very reasonable prices. I settle for rice, chicken wings and salad at eight euro fifty. Lina and Sine order two wraps, at four euro fifty. Our night ends at the Stadtgarten, where we drink some Jever beers.

The following day I’m invited to ‘Writers Soup’ by Dr Roberto Di Bella at the Literaturhaus Köln. He is the founder of this international writers cafe, which deals with the situation of writers living in exile. They meet once a month over soup to exchange ideas and network. I meet about twenty-five writers from Afghanistan, Tunisia and Syria and I listen to poems and short stories in many different languages.

The highlight of my stay in Cologne happens the next day, when Sine and I visit the Shaka Zulu restaurant on Limburger Street in the Belgian Quarter. We meet at the Stadtgarten at nine in the evening, and make the ten minute walk to the restaurant. There are a few people hanging around outside when we arrive, and when we step inside there is a buzzing South African atmosphere, from the smell of food to the house music—Black Coffee—and the decorations. I feel the Rhine-South African connection strongly. We introduce ourselves to the co-owner, Shamran Golestani, and he’s very excited that we’re South Africans. He immediately asks the barman, Said, to give us shooters—Springboks and Soweto Toilets. Alcohol-free cocktails include the Virgin Zulu Breezer, Shaka Zulu Breezer, Soweto Sling, Cape Town Crushed and Clifton Sunset, all between three euro fifty and eight euro. Apart from the predictable pap, you can also get Botswana seswaa beef and Mozambique fish stew at between seventeen and twenty euro.

‘My business partner, Paul Stern, is an opera director from Cape Town. His parents are Polish,’ Shamran tells us. ‘I’m an architect. The restaurant has been going for five years.’

Sine is happily sipping her Savanna cider, and Shamran puts Zahara’s ‘Umthwalo wam’ on the sound system. The waitress comes over and introduces herself as Ewa. Like Said the barman, she is wearing a traditional shirt resembling those worn by Ladysmith Black Mambazo. Toklee greets us from the kitchen, and Shamran plays ‘Makalanyane’ by Vusi Mahlasela. But it is the song ‘Khona’ by Mafikizolo that gets everyone on their feet. Two women who were sitting outside, African Americans from New Jersey, begin dancing as they walk inside. We dance to South African music until they close at around eleven.

Cologne’s pubs and restaurants operate twenty-four hours a day, depending on the number of customers. Maybe that’s why to me Cologne represents joy. If you allow yourself to breathe the city’s air, you will glow with the ecstasy of an escape into a world you prefer, while barely realising it. Cologne is one of those beautiful German cities waiting to meet you, waiting to be talked about, to be found out, to be made friends with. And, I warn you, it is nearly impossible to leave without feeling like you are absconding. This is Cologne. Its beauty will haunt you—pleasantly—for a long time. It fills you with wonder by day, and enchants you by night.

- Niq Mhlongo is City Editor; his latest book is an anthology of short stories, Affluenza; follow him on Twitter

A brilliant piece, like all of Niq’s writing. At least Germany was not all beer for him. I had been thinking his was a beer residency in Cologne!

As a resident from that region, i m glad that he enjoyed his stay. I m a bit surprised though. After all, nobody here would call Cologne “beautiful” when he talks about the City as a whole. But i guess this is the disadvantage of living long enough here: you get to see all the ugliness, even if you dont want to 😛

Great piece Niq. I have read all your hitherto books. Excellent write up on your life in Cologne makes one to want to visit the place. Iam impressed with your your your journey there and would one day want to folliw suite.

In a small way I am now busy preparing for appearence and featuring of my collection ofof short story book Camdeboo Stories publised by Patridge 2017. Inbox me an address in SA and I’ll courior it to you.

Mzuvukile Maqetuka