Lidudumalingani won the 2016 Caine Prize for African Writing for his short story ‘Memories We Lost’. As part of the prize he visited Georgetown University in Washington, DC, for a series of seminars, readings and events, and made a trip to New York. Here he shares his impressions of the cities.

When I finally file out of the Dulles International Airport in Washington, DC, after multiple security validations, as they call them, it is pouring with rain. Airports are self-contained worlds with an atmosphere and evidently a weather of their own. The Dulles Airport strikes me as small but neatly built, such that everything appears to exist on its own. The currency exchange office is tucked away in a corner by itself, as is the information desk, which is by the driveway to the underground parking. It is at the information desk that two aged white men tell me where to get a shuttle to Union Station. On the map, Union Station appears to be within walking distance, but after thirty minutes of sitting in the shuttle I realise that I had fallen victim to the deceiving nature of maps. One can trace one’s hand across continents, across a distance that can only be covered by many hours of travelling.

Because it is raining, the world outside only exists in pieces; only when the rainfall has subsided is it a thing to be pieced together and made sense of. The shuttle driver is on a call with someone that he keeps asking, ‘What did I say to you?’ It is only when the woman seated next to me receives a phone call that I get to hear someone else’s voice. From the way her demeanour suddenly changes, moving from being tense to crossing her legs, stroking her ears and lowering her voice, I come to the assumption that she is talking to her lover. It occurs to me when another man makes a phone call that here we were, four complete strangers, having conversations that extend beyond our own presence in the shuttle. That we are here as more than one person, that there is a part of us that exists elsewhere. This happens often for me during morning and afternoon commutes on public transport. What is each of these hearts carrying? What kinds of love are they leaving at home? What kinds of hurt are they leaving behind in the morning and returning to in the evening?

When we finally approach Union Station, the traffic is backed up to at least a five-minute-long walk to the entrance. I jump out of the shuttle and make a run for it, dragging my bag in the puddles of water.

When I board the Amtrak train at 3pm, I have been travelling for two days, having boarded a flight in Cape Town to Dubai, then Dubai to Washington DC, and have only slept for a fraction of that time. Depriving someone of sleep is a form of torture, this is well documented, but in my case, nobody is to blame for my torture. I alone had made the decision to watch seventy per cent of the catalogue of movies on the Emirates flight instead of sleeping. On this journey, though I am usually specific about what movies I watch, I had made the decision to watch only action movies. The senseless violence, frantic camera movement and absence of storyline appeared to be the best way to while away the time, over twenty hours’ worth.

On the four-hour long train ride to New York, then, I dip in and out of sleep, such that every time I open my eyes, for a moment, there is the sense that the train is travelling in a different country altogether and I have no idea where I am and what day it is. The concrete structures of DC give way to industrial Baltimore and then, for most of the journey, the countryside, and then New York, with shining buildings of all shapes further away, beyond the weeds.

In 1950, the writer Truman Capote travelled to Spain and wrote a short piece about it for the New Yorker, a piece in which he demonstrates a keen sense of observation. A few years ago the New Yorker opened its archives, making available for free a vault of pieces by writers who became legends when they wrote as if they had everything to live for; writers who if it were not for their writing, my own would not exist. This is how I came to read Capote’s piece, which is titled ‘A ride through Spain’. I thought of this text as I stared out of the window of the train, beyond an elderly woman in an orange top and brown tracksuit pants. On the opposite seat, a woman sat high up in her chair, her legs folded into her chest and her arms wrapped around them as if to keep warm. The day was well into the afternoon and the sun had long been up and there was not, especially in the train, any cold breeze.

When the train pulled into New York the city was settling into the evening, and though it had stopped raining by then the streets were still wet, with the lights bouncing on the wet roads; a glimmer that has a beauty of a kind that can only be captured in images. Across from the train station, still disorientated, I waved down a yellow taxi and made my way to my hotel, although I had no idea where it was or what it looked like, and could not, after travelling for more than twenty hours, be bothered to look it up. As the cab swerved into short streets and then turned into a longer one, with red and yellow lights at the entrances of nightclubs and party revellers walking up and down, I thought of the scene in Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver when Travis Bickle, played by Robert De Niro, is in a cab, driving past nightclubs.

My stay in New York was brief, so brief in fact that I did not see many of my plans through, one of which was to make my way to Central Park West and 102nd Street, where Nat Nakasa plunged from his friend’s seven-storey apartment to his death. There was no clear motivation behind this planned visit, only that I seem to have an inclination for such visits. Whenever I travel, I make plans to seek out places that have a connection to writers. When I travelled to London, England, in 2016 for the Caine Prize, I made a trip to Oxford, the city where Dambudzo Marechera lived. I had no clear plan then either, and every time people asked me about what I was planning to write, my answer was that, well, writing comes to me, I will see what comes when I am there. The same impulse drove me when I was in Abeokuta, Nigeria, and I made plans to photograph the house where Amos Tutuola had lived. There is something appealing about walking in the same footsteps as these writers, both physically and metaphorically.

In the seventy-two hours I was in New York, over a weekend, I must have walked an average of twenty-four hours. One morning I decided against catching a cab, and instead chose to walk to the Whitney Museum, the Hudson River and the Blue Note Jazz Club. On the last evening I walked across the Brooklyn Bridge into Brooklyn. New York does not have a moment where it pauses and I found it impossible to photograph, except when I found a jazz band playing in a public garden, a rare moment of stillness. Besides that, I was overwhelmed by the number of people and the tall buildings that offered no respite from the feeling that New York was closing in, suffocating me.

The rest of the time in the US I spent at a two-week residency at Georgetown University in Washington, DC—where I occupied, in her absence, Aminatta Forna’s office, and during which I honoured two readings and visited three classes, speaking about my own work, African writing and African films. It was while at Georgetown that it dawned on me what I have become. On the day of the reading, which was preceded by an hour-long discussion of my writing, photography and filmmaking, I found posters of my event plastered all over campus and a feeling of not being worthy came over me. It is one thing to spend the early hours of the morning, when everyone else is asleep, writing, and quite another to see your face all over a university in a foreign country, and to have people make no other plans except to come and hear you talk and read. That event unfolded into a beautiful evening of reading, conversation and realising that writing is sometimes like a thread that weaves all our hearts into one.

During my last days in Washington I tried to make it to the museums, without much success. The queues were too long, bending around buildings, spilling onto the streets. And, as such, in the company of Arao Ameny, a Ugandan journalist based in the USA, I only saw the National Museum of African American History and Culture from a distance. The 29,000-square-metre building was designed by Ghanaian British architect David Adjaye, and as it sits there it is hard to believe it was only opened on 24 September 2016. It is impossible to imagine what the space looked like before it existed. Even from a distance one cannot help but be struck by the three-tiered design, covered in bronze plates, which is inspired by a wooden sculpture of a man wearing a crown by the early-twentieth-century Yoruban artist Olowe of Ise.

The last thing I did in Washington, before heading back to South Africa, where I had not been for over two months—I was beginning to long for its familiarity—was to go to a Theaster Gates show, an installation artist I most admire, and I was spectacularly disappointed. There were two things about it that I found to be most annoying: one, an elderly white women kept reiterating that Gates ‘uses the fabric of society to create his work’, and the other, that the deejay was one of those overzealous types who are only, and utterly, interested in themselves, which manifests into their song choices. In the entire time that I was there, with Zachary Rosen, a photographer friend based in Washington, our conversations were drowned out by the loud music, and we escaped into the evening and headed to a club for some dancing.

On the day I catch my flight back to South Africa, a Saturday morning, I am late by at least two hours for the time that I had earmarked as being ideal for waking up, and I only have time to grab my bags and check out of the house I had been staying in, a beautiful house on the fourth floor on 19th Street NW, which overlooks a street lined with trees. I make it to the airport on time, but when I smell my armpits I know that the next twenty hours will be uncomfortable. I get home and immediately take a shower. I stand in the shower for what seems like an eternity until I feel my body falling asleep, though my eyes are wide open, and I jump out and throw myself into bed, and wake up almost two nights later and feel like my body is not me but a thing I am carrying.

Index

Authors

- Truman Capote, Aminatta Forna, Dambudzo Marechera, Nat Nakasa, Amos Tutuola

Artists

- Theaster Gates, Olowe of Ise

Awards

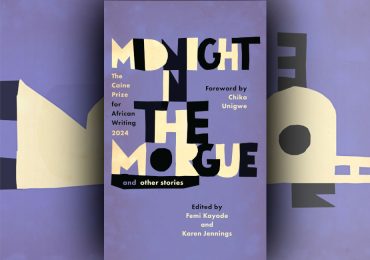

- Caine Prize for African Writing

Places

- Abeokuta, Blue Note Jazz Club, Dulles International Airport, Georgetown University, New York City (Central Park West and 102nd Street), Oxford University, Washington, DC, Whitney Museum

People

- David Adjaye, Zachary Rosen

Topics

- Photography, Trains, Travel